For many, the goal of independence itself overrides any fears of economic consequences. But faced with a vote that will have a huge impact on future generations, I believe that is a luxury we cannot afford. The key question has to be whether or not we will be better off or poorer as a separate country.

When I was reluctantly drawn into the debate, I said that it should not be about nationalism, but growth and economic success, and the quality of our citizens’ lives and all that goes with that. Against these measures, it’s very hard not to conclude the case is heavily weighted towards Scotland remaining in the UK and getting the best of both worlds.

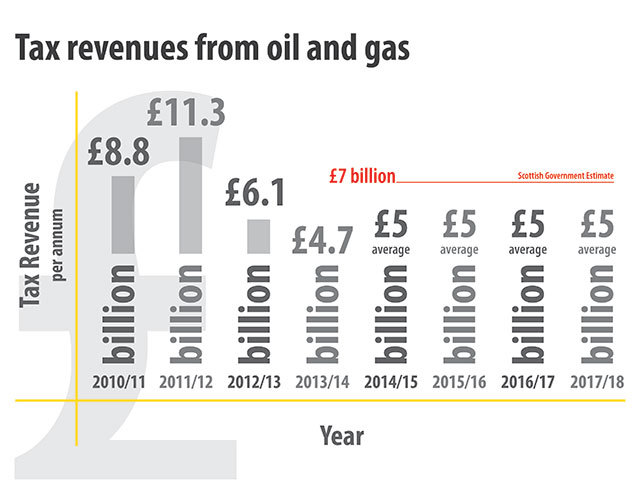

Oil and gas plays a major role in our economy, supporting 220,000 jobs in Scotland. The possible oil tax revenues to an independent Scotland feature strongly in the Scottish Government’s economic predictions, not as a “bonus” but as a means of balancing the books, without which they cannot pay for the promised improvements to healthcare, education and social services.

This is why I felt it was vital that people were aware of how much oil can still be realistically recovered, for how long and what impact that has on public spending.

Scots deserve the facts, not wildly exaggerated claims about existing or potential reserves, nor spin about new discoveries such as the headlines last week that Professor Alex Kemp, the guru in forecasting UK oil production, was predicting an “oil bonanza” in the North Sea. He completely denied this at the end of the week and acknowledged that old information was being abused. There was also a report from an organisation called N-56, sponsored by the Yes Campaign, which forecasts a big increase in recoverable oil from unconventional shale. This is highly speculative and depends on technology not yet tried offshore, incredibly expensive wells into shale rock from which it is likely the oil has already largely leaked. It is a blatant attempt to manipulate voting sentiment.

With no allegiance to any political party or campaign, but with over 50 years of North Sea oil and gas experience, I provided my views with the aim of injecting realism into the debate.

I am pleased to say my assertion that what’s left to come from the UK North Sea up to 2050 of between 15 – 16.5 billion barrels now appears to be generally accepted. Professor Alex Kemp and Melfort Campbell, who led the Scottish equivalent of my Review, agree. It is the mid case in the industry body Oil & Gas UK’s estimates

Scottish Government, however, still uses up to 24 billion based on a number of possible small field developments after 2050. These are marginal fields which currently can’t be developed. It is possible that technology and a significantly increased oil and gas price may enable some of them to be developed, but the outcome won’t be more than 1-2 billion barrels and there will be virtually no tax

revenue to Government because marginal fields are less profitable and, will likely require tax incentives to get them going.

My figures takes account of anticipated benefits from a fiscal review underway and also the introduction of the proposed new Regulator, but there are also deteriorating industry trends. Exploration is at an all-time low. In the last two years we have only discovered 150m barrels against the 5bn required to achieve 15-16.5billion. Industry costs have increased five-fold over the last 10 years, making a number of fields unviable. The industry is struggling with poor production efficiency; we are producing less at higher cost and therefore contributing less in taxes per barrel. All this is compounded by the ageing infrastructure – platforms and pipelines – which need to be maintained or replaced.

But the most important aspect in the debate is the rate at which oil production is declining. In 1999, we were producing 4.6million barrels of oil per day, today we are producing 1.45million. In 2030, this will be down to 1.1 million and by 2050 to around as little as 200,000 – 250,000 barrels.

What this means, and bearing in mind the fiscal income to Government will come down faster than production because of the higher costs of ageing fields and the need for incentives for marginal fields, is that there will be very little fiscal income available to government from 2040 and virtually none after 2050.

Scottish Government’s response to the depletion challenge, which will give them virtually no oil and gas income by 2050, is that they will replace this over time by increasing productivity, enhancing our manufacturing base, and taking in more immigrants, among other measures. These entail a significant degree of risk and the ability to compete internationally. There is no guarantee of success, leaving a huge economic challenge for our children and grandchildren.

Young people voting this week must be aware that by the time they’re in their forties, Scotland will have little offshore oil and gas production and this will severely hit our economy, jobs and public services.

It was clear from my in depth Oil & Gas Maximising Economic Recovery Review last year that the operators on the UK Continental Shelf would definitely be more confident in dealing with a UK Government than a Scottish Government. Both BP and Shell at top level have again confirmed this last week. This is not a negative comment on Scotland, simply acknowledgement that they’d rather deal with a larger UK economy. And the currency will worry them, so it will definitely be more difficult to attract the essential new investment in the North Sea under an independent Scotland.

There will be inevitable uncertainty for a fair period of time during negotiations and this would come at a critical time in making the essential adjustments to the UKCS fiscal regime to maximise the recovery and in getting the new Regulator up and running. There’s a danger that we’ll find ourselves struggling to even get to the lower end of the estimates i.e. 12billion barrels.

Regardless of the outcome of the referendum, we are facing some tough times

ahead as we adjust to a post-oil economy. I strongly believe that we will be able to weather that storm much better and less painfully within the shelter of the UK, as part of a larger, stable economy.

Having been drawn into the debate unwillingly, I have been shocked at the amount of mis-information and spin. I’ve also been shocked at the extent to which nationalism for Scotland has been superseded by sentiment against Westminster and the UK. I firmly believe this is probably the most important vote Scotland will ever have and we mustn’t let our fervour for nationalism overcome our responsibility for providing the best possible economic future and opportunities for our children and grandchildren.

When the country goes to the polls this week, my hope is that every voter weighs up the economic consequences, based on the facts not the spin, and asks themselves not can we go it alone, which we undoubtedly can, but would we not be a lot better off by further developing the best of both worlds.

Recommended for you