Stranded in Burkina Faso by the 2010 Icelandic volcanic eruption while deprived of cigars, books and the assorted pills required by the over-70s, Algy Cluff decided the time was right to return to the North Sea.

The entrepreneur left the basin on a high nearly 40 years earlier after his company’s discovery of the Buchan field, before running several fruitful mining ventures in Africa. Now 76, Mr Cluff is in charge of another independent UK oil and gas company which is building up its portfolio of North Sea licences.

Asked where he gets his energy from, the father-of-three said: “I don’t know. It’s not as if I’m Tarzan or anything. I’m physically quite frail, but I’m a driven man. I had a comfortable upbringing, but there’s something in my psyche that drives me on. I have a determination that my children should have a father who does not give up and who leaves the house at 7.45 every morning and doesn’t usually come home until 7.45 at night.”

Mr Cluff’s memoirs, Get On With It, show he has had quite a life. He has teased Margaret Thatcher, cultivated a business relationship with Robert Mugabe, only for it end with Mr Cluff fearing he was going to be shot, and has had his house searched amid suspicions Lord Lucan was hiding out there.

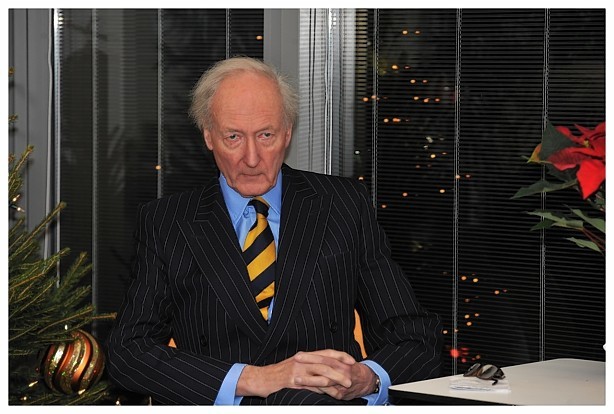

His stern, schoolmasterly appearance, particularly in photographs, belies his friendly and humorous nature. Mr Cluff – who married his wife, Blondel, in his early 50s – laughed a lot more during the interview than might be expected of someone who had just completed a near four-hour drive to Aberdeen from Dornoch, where he has a holiday home. “I’m a bit frazzled,” he conceded on arrival. In a prolific career, he has established at least five companies carrying his name, including Cluff Oil, Cluff Gold and his current vehicle, Cluff Natural Resources (CNR). “One of the rules of the oil business is that the more grandiose the name the smaller the company,” he observed.

But before any business ventures or oil finds came along, Mr Cluff, whose family home was in Cheshire as a child, enjoyed the “happiest part” of his life serving in the Army. His time in the Grenadier Guards and the parachute regiment took him to Cameroon, Cyprus and Borneo: “It was an intense and enjoyable six years. It did more for me than university would have done. It brought out the best in me,” he said.

During a stint in the Borneo jungle, where it was his duty to watch a river crossing for invading Indonesian forces, his mother arranged for food hampers to be air-dropped to him along with the standard rations. “Its parachute failed to open and we mournfully scraped fois gras off palm fronds and were violently sick,” Mr Cluff recalled.

In the mid-1960s, during a period of leave from the jungle, his career in business lifted off. The setting was a bar in Singapore, where he was introduced to entrepreneur and planter Charles Letts, who died in 2013 after three-quarters of a century in south-east Asia. On Mr Letts’s advice, Mr Cluff convinced his generous father to invest in rubber and oil plantations which turned out to be worth a fortune – as they occupied swathes of land around the rapidly expanding conurbations in Malaysia.

Mr Cluff sen made a mint and passed the profits on to his son, who subsequently “glided about” for several months, buying a bookshop, becoming an associate with the Ionian Bank, where his interest in the oil business was aroused, and, generally, increasing his social mobility. His one foray into politics came in 1966, when he contested that year’s election as a Conservative candidate, but was defeated hands down.

Then, while leafing through a newspaper, he noticed a North Sea licensing round was to take place and that applications could be made free of charge.

Cluff, Charterhall and Partners (CCP) was established to challenge for the licences and was granted a number of blocks, one of which was Buchan.

The field was first drilled in 1974 and lies 120 miles north-east of Aberdeen. CCP’s value soared to £20million, but was soon bought out.

Mr Cluff’s involvement in the North Sea had temporarily ended. There were attempts to strike oil again, but while a venture in Australia brought modest success, another in China was a bust. One scheme in Guatemala fizzled out in farcical fashion, when the country’s president was to open the faucet meant to release millions of barrels of oil. “The national anthem was played, there was a roll of drums and the president stepped forward and turned the faucet. There was a gurgling noise and a huge black spider emerged… unaccompanied by any oil,” said Mr Cluff, who spent the first half of the 1980s as the proprietor of The Spectator and was chairman for a further 20 years.

Most of the North Sea interlude was spent in the gold mining business in African countries, including Zimbabwe, Ghana, Tanzania and Burkina Faso, but the oil and gas bug never truly died.

After his brief period of enforced reflection in Burkina Faso, Mr Cluff lost a year trying and failing to buy some North Sea production, convincing him to explore another avenue.

“I remember I was on a North Sea rig in 1973 looking at readings and was very impressed to see how thick the coal seams were. Someone else said there was enough energy in that coal to keep Europe going for 2,000 years. That remark stuck in my head. I was wondering what my next move should be and thought I’d examine underground coal gasification (UCG). I enlisted the help of two former coal board members and it became apparent there was an enormous source of energy around our shores which can now safely be converted into syngas. I was not only advised that it was safe, but that it was also a type of North Sea Mach II.

“I thought that because we’d started decommissioning platforms at huge expense, many of which are beside massive seams of coal with pipelines lying empty – why could they not be put to work? We’d be protecting jobs and using infrastructure that is already there.

“I persuaded myself it would be in the best interests of Britain’s energy security and embraced it as a pioneering endeavour. In hindsight I should not have done that without enlisting support from a major company.”

Mr Cluff had planned to trial UCG – which involves converting underground coal into gas through heating it – in the Firth of Forth, but he was scuppered in October, when the Scottish Government added the technique to the moratorium on shale, a decision which rankles with the businessman. He changed tack and decided CNR should focus on conventional gas deposits, amassing 11 blocks in the southern North Sea. “Securing those blocks allowed me to pick up where I left off in the 1970s. We’re now engaged with that. We’re studying seismic data and seeking partners for a drilling programme.”

The company is scouting around for other opportunities to acquire licences and recently agreed a deal with Verus Petroleum which gives CNR an option to buy the rights to 100million barrels of oil for about £1. The 29th licensing round could well yield more for CNR, which is in the enviable position of being debt-free.

Which brings us to the present. So, aside from re-conquering the North Sea, what else does the future hold for Mr Cluff?

For one thing, he is keen to write more: “I’ve got a feel for unsung heroes – people who have done things of great importance but of whom no one has ever heard, but I won’t mention any names because someone might steal them. I’ve got a list of them.”

Recommended for you