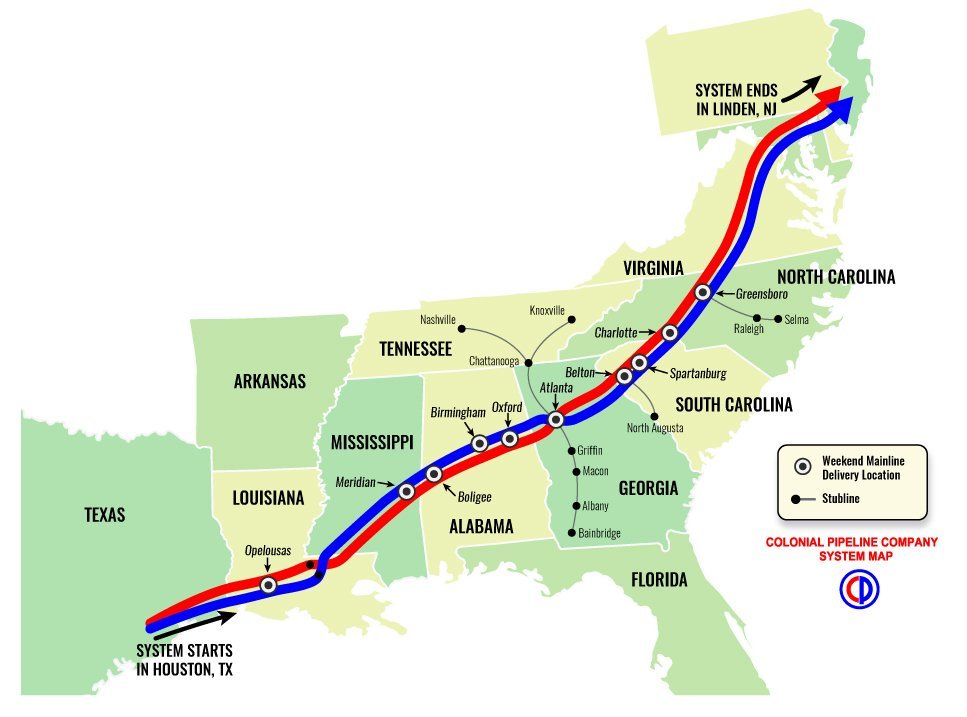

A 40-inch-wide pipeline that snakes its way from the oil-soaked Gulf Coast to the tank farms of northern New Jersey carries a quarter of the gasoline used by East Coast motorists.

On Monday, that thin lifeline snapped after an explosion and fire in Alabama. The fallout: For the second time in two months, the price of fuel for truckers, commuters and soccer moms threatened to jump, even as global crude prices decline.

Why is such a huge, economically dynamic region so dependent on one pipeline network for so much of its gas, jet fuel and other petroleum products? Think economics, and the environment.

“The economic case isn’t giving you a reason to build and the environmental opposition is the reason you don’t,” said Kevin Book, managing director at Washington-based consultancy Clearview Energy Partners LLC. “At this particular point in history, no products pipeline is going to be an easy build.”

A spill in September shut the gasoline line for 12 days, cutting supplies to 50 million Americans in the U.S. Southeast. Monday’s explosion is expected to close the line until Saturday, according to Colonial Pipeline Co., which operates the system. It’s sending futures prices surging and gasoline traders scrambling for other ways to supply East Coast states with fuel.

Tighter Supplies

Even if the pipeline restarts on Saturday, major Southeastern cities like Nashville, Tennessee; Atlanta; and Charlotte, North Carolina, will face shortages, according to Andy Milton, senior vice president of supply and distribution at Mansfield Oil Co., a Gainesville, Georgia-based fuel supplier.

“It’s not going to be Armageddon, where people would have to walk to work,” Milton said by phone. “We’re doing everything we can to supplement the pipeline being down right now. But logistically, there are only so many trucks and drivers. You’re kind of plugging holes.”

December gasoline futures jumped as much as 21.56 cents, or 15 percent, to $1.6351 a gallon on Tuesday as the pipeline’s shutdown threatens supplies. The contract, which is for fuel delivered into New York Harbor, was down 1 percent at $1.4697 on the New York Mercantile Exchange as of 1:11 p.m. Hong Kong time on Wednesday.

For consumers, prices at the pump will probably drift higher in some parts of the southeast, said Patrick DeHaan, senior petroleum analyst at GasBuddy.com, a company that tracks retail prices and availability. At the peak, price increases could average 15 cents, he says. And if the restart is delayed, “you’d see more of a price impact.”

Colonial opened for business in 1964, connecting Houston’s refineries with Linden, New Jersey. Eight oil companies spent $370 million on the system — at the time the biggest single, privately financed construction project in U.S. history, according to the company’s website.

Colonial’s system carries 2.6 million barrels per day, just under half the 5.38 million barrels a day of refined products used across the East Coast in August, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Another 700,000 barrels per day run through a system operated by the Plantation Pipe Line Co.

The accident is set against a backdrop of rising protests against oil-infrastructure proposals, from the Keystone XL project to the $3.8 billion Dakota Access oil line. In Georgia, Kinder Morgan Inc. canceled the Palmetto refined products pipeline, meant to serve the southeast, after state lawmakers imposed a moratorium on new permits.

“When we make a decision against individual pipeline projects, over time that adds up,” said John Stoody, a spokesman for the Washington-based Association of Oil Pipe Lines.

“If you’re a company thinking about a new pipeline to service the northeast and you wondered whether it would be received favorably or even fairly or objectively, you would only have to look around at some of the other projects,” he said in a telephone interview.

Environmental opposition aside, a new products pipeline to the East Coast may not make economic sense for companies, said Clearview’s Book. Colonial and Plantation serve most of the market, and there’s little sign that demand will grow enough to justify another competitor, he said. And as shown in the latest outages, traders can quickly divert supplies from other countries when needed, he said.

“It’s hard to compete with the economics of scale and incumbency” of the existing lines, Book said by telephone. “What’s the business case if you’ve already got a multi-million barrel conduit serving the region?”

The U.S. also created the 1 million-barrel Northeast Gasoline Supply Reserve after Hurricane Sandy plowed into the Northeast four years ago and disrupted deliveries, though that wouldn’t be enough to cover a long-term shortage, he said.

The rally in gasoline futures boosted profits collected from importing European gasoline to a four-month high, PVM data compiled by Bloomberg show. Freight costs for cargoes across the Atlantic surged 78 percent to $16,308 a day, the highest returns possible on that route since January, Baltic Exchange data show.

When there is a disruption on Colonial’s product lines, there are several alternatives to moving product, Ezra Uzi Yemin, chief executive officer of Delek US Holdings Inc., which operates refineries in Texas and Arkansas, said Tuesday.

“Either barrels come from Canada or, if it’s a long-term disruption, people will start barging up the East Coast to the Northeast,” said Yemen, speaking on the company’s third-quarter earnings conference call. “But I do not believe this is a long-term situation.”

Recommended for you