Friday’s jobs numbers confirm one thing about this week’s OPEC agreement: Shale producers were readying to raise production weeks before officials gathered in Vienna.

Unlike the government’s overall employment numbers, much of the data on oil-and-gas extraction and support workers comes out with a one-month lag. So what follows concerns October.

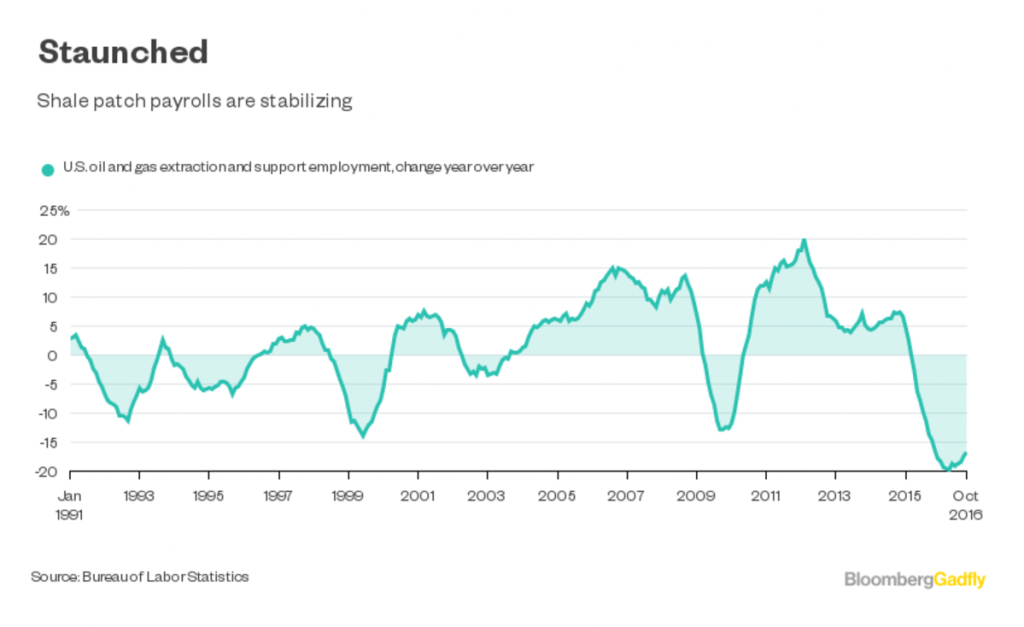

The bleeding in the U.S. shale patch has all but stopped. While another 700 support jobs were lost, October was the first month since the oil crash began when that number was less than 1,000. And extraction jobs — the higher-paid professional positions — were stable (and actually increased slightly in November ).

Apart from overall payrolls, there are other signs of strength in the data. Extraction employees clocked an average work week of 41.8 hours, their longest since March 2015, and hourly earnings were up 4.5 percent year-over-year. Support workers have less leverage but still got a 2.3 percent bump to wages — a clear acceleration since the summer — and worked more hours than they had in 21 months.

Oil & Gas Jobs Lost In The Past 2 Years

154,000

Wage inflation will reinforce concerns about the E&P industry’s touted efficiency gains in the downturn being cyclical. Still, as a proportion of estimated revenue, payrolls look pretty stable, if elevated compared to before the crash. As usual, I’ve used production data from the Energy Information Administration to calculate a crude revenue number for the industry and Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers to estimate overall wages:

We’ll have to wait until 2017 for the November numbers, but I’m guessing wages ate up a bigger share of revenue, given the way oil and gas prices slumped for most of last month.

But OPEC’s capitulation on Wednesday means E&P firms likely won’t be bothered by that too much. The jump in prices since then means December’s figures, due out in February, will look healthier, and the prospects for raising more capital look better already.

This is OPEC’s dilemma. The flood-the-market strategy of the past two years clearly took a toll on U.S. rivals — just not as much of a toll as expected. And while OPEC producers can pump barrels at a lower cost than virtually anyone in strictly operational terms, their strategic U-turn this week shows they have other big costs to factor in: namely, social compacts to keep restless populations onside (see this great blog post by oil consultant Geoffrey Styles for more on this).

Just as OPEC was reaching the limits of its endurance, America’s frackers were showing the extent of theirs.

Recommended for you