What’s the most important innovation behind the rise of renewable energy: Taller wind turbines? Smart power grids? Spray-on solar cells?

None of the above. For all the advances made by engineers that cut the cost of solar modules and new wind generation by more than half in five years, the true heroes of the renewables revolution may be a group that’s rarely recognized: accountants.

To see why, consider the headlong growth of corporate power-purchase agreements — contracts where major consumers strike deals with generators to buy a fixed quantity of electricity over a decade or so.

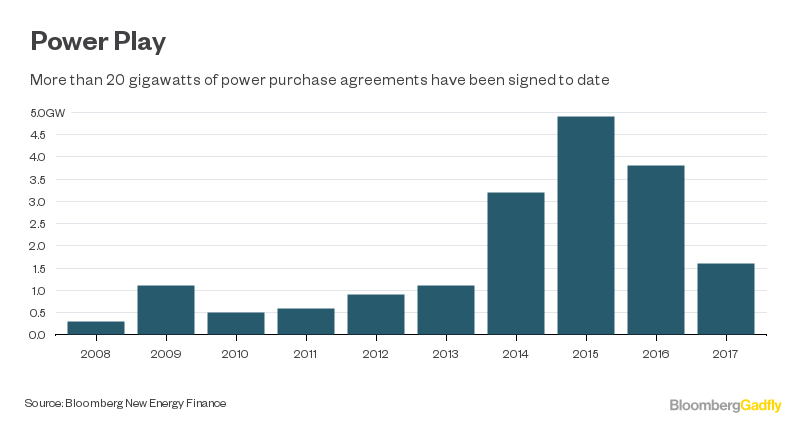

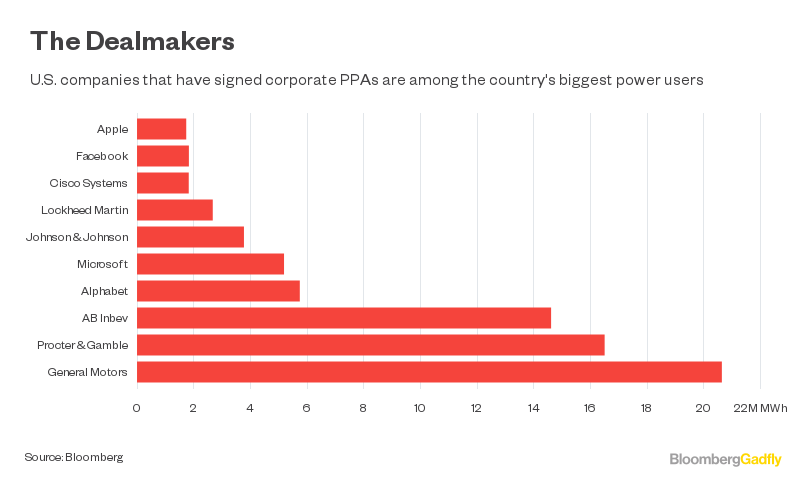

From humble beginnings around 2008, when the likes of Alphabet Inc., Apple Inc. and Facebook Inc. starting taking out PPAs to power their vast data centers, these agreements grew by leaps and bounds. In the latest, between Anheuser-Busch InBev NV and Enel SpA last week, a wind farm in Oklahoma will supply half of the brewer’s U.S. electricity demand, sufficient to produce 20 billion beers a year.

The capacity of renewable PPAs signed to date is more than 20 gigawatts, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance’s Justin Wu, greater than the generation capacity of Switzerland or the Philippines.

Promising to power your business with 100 percent renewable electricity certainly produces a warm fuzzy feeling in executives, but the success of PPAs can’t be put down to that alone. Far more important has been the greatest force in financial markets: risk.

Power is one of the largest costs for many enterprises. Among the growing group committed to 100 percent renewables, Alphabet consumes 5.7 million megawatt hours a year and Anheuser-Busch InBev NV uses 14.6 million MWh, with electricity forming the lion’s share.

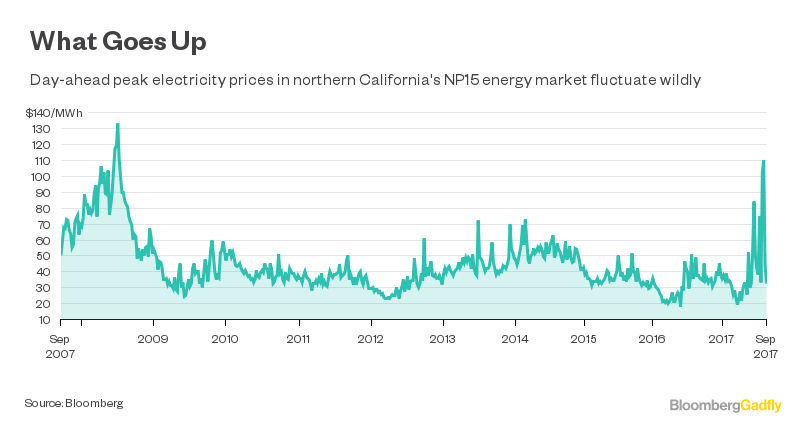

It’s hard for businesses to control this cost. In the NP15 energy market that serves Silicon Valley, spot day-ahead electricity prices have veered as low as $20/MWh and as high as $130/MWh over the past decade.

When many of the initial corporate PPAs were inked in the late 2000s, most of the energy industry believed those costs would jump as a result of robust wholesale gas prices; they slumped, instead, on a shale-induced glut. An agreement with a generator to provide fuel-free electricity at a fixed cost was an attractive alternative.

Paying a premium for certainty in this way is the lifeblood of finance. It’s the reason the $500 trillion derivatives market exists: While it’s possible that a hotel chain or auto manufacturer could get a leaner interest or exchange rate by buying at spot prices, they’d generally prefer a guaranteed rate, and pay for the privilege.

It’s not so different with energy. By entering a PPA with a renewable company whose generation costs are more or less fixed at the commissioning stage, a consumer can guarantee to meet its energy demands at a set price for years. And the generator wins a major customer whose promised cash flows can reduce the finance costs of building the plant in the first place.

As costs of renewables move to, or below, parity with fossil fuels, those advantages are turbocharged. When solar or wind can be bought directly from a generator for less than it can be had from a utility, why would a major consumer not go for the lower-cost, higher-certainty option?

The next leg of demand is likely to come from emerging markets, where big companies such as Apple are committing to decarbonizing manufacturing supply chains and where, in many cases, sufficient renewables capacity doesn’t yet exist.

In Mexico, about 3.8GW of PPAs have been signed by the likes of ArcelorMittal, Wal-Mart Stores Inc., Coca-Cola Femsa SAB, Nestle SA and General Motors Co. in recent years, according to BNEF and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development. India, where HSBC Holdings Plc and Delhi Metro Rail Corp. signed solar PPAs in recent years, and 2.3GW are outstanding, is likely to be another growth area.

The rise of the PPA won’t be without stumbles. Utilities receive fees for transmitting PPA electrons, but are mostly losers in these deals.. Given many are state-owned or carry lobbying weight, that could become a roadblock.

In countries that encourage renewables developers with feed-in tariffs above wholesale prices, such as Germany, generators have little incentive to sell into a more competitive corporate market.

And falling costs of renewables could put major consumers off PPAs if they think they’ll get a better deal later. That’s a major problem in India, where state governments have been attempting to renegotiate wind-power agreements at lower prices.

Still, if you’re seeking an explanation for the growth of renewables, don’t save all your praise for the whizz-kid physics Ph.D.s building a better sun trap. That bean-counter spending her days tweaking cashflow spreadsheets may just be saving the world.