It’s been a bad year for oil explorers in Norway’s Arctic: a record campaign in the Barents Sea yielded little; the most exciting well in years proved to be a flop; and Norwegians grew increasingly skeptical about the industry that made them rich.

But companies led by Norway’s state-controlled Statoil ASA and Sweden’s Lundin Petroleum AB aren’t about to give up.

The Barents is thought to hold the bulk of the country’s undiscovered oil and gas resources, and is seen as key to maintaining production 10 years from now as older fields decline. The area has scarcely been explored, with just 1/10th as many wells as the North Sea — and vast swaths of it aren’t even open to drilling yet.

“The Barents in particular is still a very long-term game,” Neivan Boroujerdi, an analyst at consultant Wood Mackenzie Ltd., said this month. “We’re not ready to write its obituary just yet.”

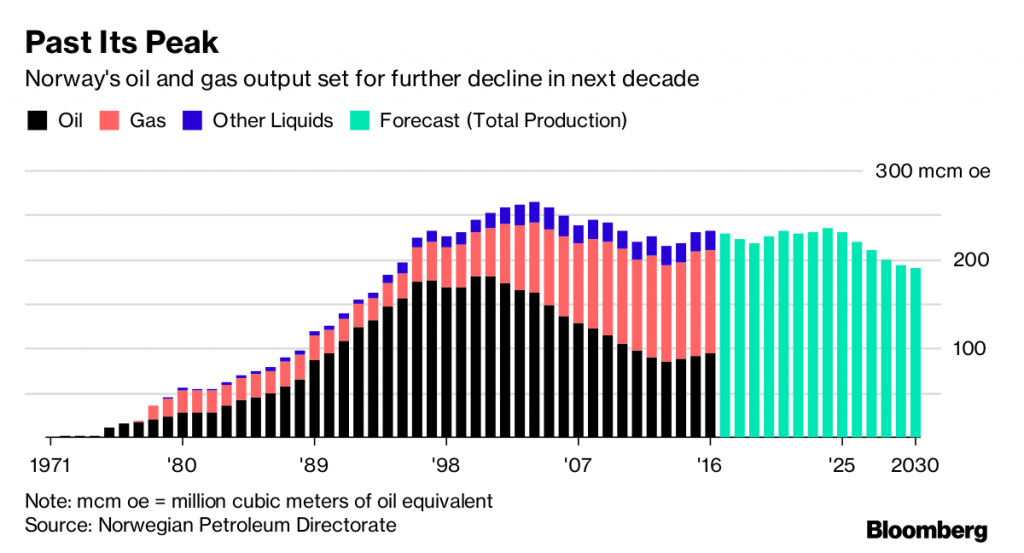

Successive governments have pushed for more activity, offering tax incentives, opening new acreage and offering blocks farther and farther north as Norway seeks to prolong the oil age that made it one of the richest countries on Earth. Crude output has fallen by half since a 2000 peak, and despite a surge in natural gas, total petroleum production is forecast to take another dive in the middle of the next decade.

Explorers drilled 15 wells in the Barents this year, two more than the previous record in 2014, according to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate.

In five wells, Statoil made only one oil discovery worth pursuing, and even that — with at most 50 million barrels — would only be developed as part of the upcoming Johan Castberg project.

More disappointingly, Statoil found only an uncommercial amount of gas at Korpfjell. The first well drilled in the virgin Barents’ southeast on the largest untested structure on the Norwegian continental shelf, it was the most eagerly anticipated prospect of the year.

Lundin found as much as 100 million barrels of oil in a well finished in January. So far this year, it has drilled one wildcat well (a probe in an unexplored prospect) that came up dry, and started another. Four appraisal wells on existing discoveries were a mixed bag, leading to both upward and downward revisions that have yet to be clarified.

Eni SpA, which operates the only producing oil field in the Barents, Goliat, struck out with its efforts.

“It’s been very disappointing for everyone,” said John Olaisen, an analyst at ABG Sundal Collier Holding ASA.

Even as wells came up dry, public opposition to Arctic exploration on environmental grounds has grown. The issue became a flashpoint of the general election last month, in which the Conservative-led government secured a narrow victory. Greenpeace is suing the country to get it to stop the latest batch of license awards in the Barents.

In an invitation to a closed industry meeting in November sent to the Petroleum and Energy Minister, the Norwegian unit of Royal Dutch Shell Plc acknowledged that “opposition to our activity is rising.”

Yet Statoil is planning another five wells in the Barents next year, including one more on Korpfjell and one in another license in a new area along the maritime border with Russia. And even if the results this year weren’t what the company hoped for, the Kayak oil discovery alone, if connected to the larger Johan Castberg development, could pay for the entire exploration effort, Statoil spokesman Morten Eek said. Statoil said earlier that its Barents wells were among the cheapest it drilled this year, at no more than $25 million apiece.

Aker BP ASA, another Norway-based producer, will drill at least two exploration wells in the Barents next year, and Lundin is planning one more wildcat that will start late in 2017 and run into 2018, according to presentation material. It hasn’t published exploration plans for next year yet.

“Lundin has long-term ambitions in the Barents Sea,” Halvor Jahre, the exploration chief of its Norwegian unit, said in an email.

Even so, 2018 will be “pretty pivotal” for exploration in the Barents, WoodMac’s Boroujerdi predicted. Another year like this one would make it hard for companies to commit to a fresh wave of wells in 2019 and 2020, resulting in a pause like the one Statoil had from 2014 to 2017 after a disappointing campaign, he said.

“The fundamentals are in place for an attractive frontier area to explore,” Boroujerdi said. “But that type of fundamentals may not stack up in a board room when people are making the decisions. If you’re not discovering anything, it’s quite difficult to commit.”