As Noble Group Ltd. sells once-core businesses to stave off creditors, it’s been running down stocks of grain, gas, power, oil and petroleum products. There’s one crucial commodity, though, that ran out long ago: trust.

The trader has often been dinged for lack of transparency, and Monday’s announcement of the sale of its oil liquids business to Vitol Group was no exception. Barclays Plc estimated in July the unit was worth at least $473 million, and at first blush an illustrative figure of $582 million quoted in Noble’s release appeared to confirm, and even exceed, this number.

When Noble’s shares opened about 90 minutes after the news, they initially traded near their previous close of 38 Singapore cents, with a few hundred changing hands as high as 38.5 Singapore cents, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Then realization started to dawn that some crucial information was buried in a parenthesis within a parenthesis in the 8,000-word document: That $582 million figure didn’t refer to the latest deal alone, but also included funds from the $185 million sale of Noble Americas Gas & Power, first announced three months earlier.

As a result, the new transaction had missed, rather than beat, expectations. Judging by the stock’s subsequent 11 percent intraday slump, Barclays wasn’t the only one expecting a higher figure.

One view of this sort of thing is that all’s fair in love and war. Noble’s announcement was opaque and its wording byzantine, but on close reading, it’s not misleading and legalistic language is par for the course in a complex agreement. If a few investors — and, full disclosure, Gadfly’s own column — initially failed to latch on to the implications, more pity them.

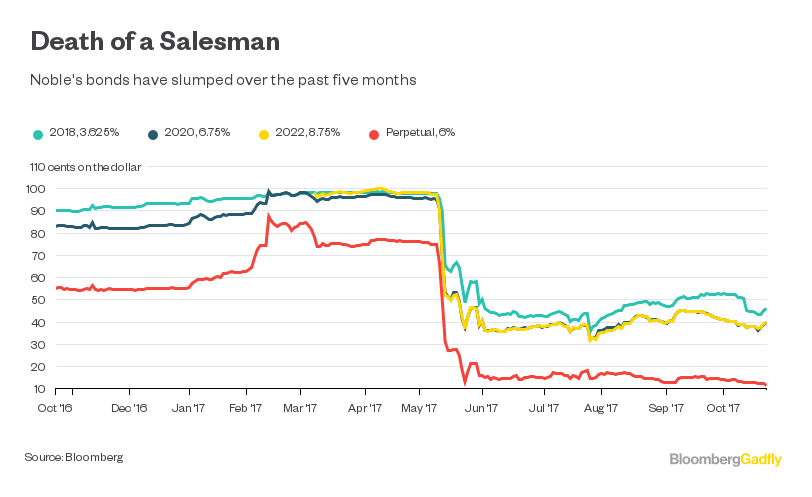

Still, legal niceties wouldn’t have stopped Noble from putting out a separate document in plain English. More importantly, while this devil-may-care attitude to communication might have been excusable when Noble was in its pomp, right now it’s a very different situation. With its operating business burning cash, Noble is dependent on the goodwill of investors to keep the show on the road. Each time it plays this game, a little more trust erodes.

Noble shares, YTD

-80%

Take the next big pot of gold that Chairman Paul Brough is planning to tap. Noble has developed a plan to generate $800 million to $1 billion of cash from selling assets outside of North America, he told an investor call in August. That sort of money could make a real difference, as Gadfly explained Monday.

You’d expect a company in Noble’s predicament to put out a pretty presentation showing which assets might be sold and how much they’ve been earning. That would allow third parties to look at comparable deals and kick some tires on the valuations being promulgated. And yet, almost three months on from Brough’s announcement, the company won’t even confirm which assets it’s planning to sell.

Arguably, that lack of trust is costing Noble real money. In all of its recent large-scale asset sales, a slice of the transaction price has been put into an escrow account to cover any post-completion valuation differences between buyer and seller. That’s a sensible approach to valuing a trading business whose working capital and debt can move dramatically day-to-day. What’s more unusual is how these escrow amounts have changed.

When Noble sold its North American Energy Solutions business to Calpine Corp. last October, just $10 million of the illustrative $1.05 billion sale price was put into escrow, or 1 percent of the total. For Noble Americas Gas & Power and Noble Americas Corp., the unit whose sale was announced Monday, the escrow figure had risen to around 44 percent.

Perhaps this is simply a matter of buyers driving a hard bargain from a desperate seller and keeping their cash out of reach of Noble’s creditors. Perhaps, too, there are differences in the nature of trading electricity, gas and petroleum that make valuations more volatile in the latter. Still, it’s hard to read the long list of escrow clauses in Noble’s sale documents without concluding that buyers are no longer prepared to lay out the full amount until they’ve performed their own checks.

At a time when Noble could use every cent, those escrow accounts are being credited with $257 million of cash it can’t immediately access.

It’s probably too late to unscramble this egg. Noble has been a black box for years, and the investors it has now are the ones with the risk appetite not to be put off. But it’s hard not to wonder where Noble would be today had it treated its shareholders less like counterparties to be exploited and more like partners to be wooed.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.