The latest Ridley Scott movie, All the Money in the World, rotates around the obsession of billionaire John Paul Getty with money and his refusal to pay the multi-million dollar ransom to free his estranged grandson from kidnappers.

Sir Christopher Plummer is masterful in the way he plays the obsessive Mr Getty, who amassed a vast collection of ancient artefacts and works of art that today are the heart of the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, which was established after his death in 1986, aged 83.

What is striking about JP Getty is the frightening similarity with Armand Hammer, whose name is forever linked with the world’s worst ever oil disaster, Piper Alpha.

The latter was also a worshipper of mammon, amassing and losing several fortunes.

Getty founded and built up Getty Oil, a highly successful petroleum company, while Hammer bought his way into a shell of a company called Occidental with a net worth of only $34,000. He was then nearly 60 and yet built Oxy into a multi-billion dollar firm.

When Oxy’s North Sea business was launched, Hammer invited Getty and the newspaper magnate Roy Thomson to join Occidental and Allied Chemical in the search for oil in the UK sector. The search led to Piper and other discoveries.

Both Hammer and Getty were totally ruthless, yet still meticulously cultivated their public images as philanthropists.

They were massively influential internationally as businessmen of supposed acumen and huge political influence. In Hammer’s case, this included the Soviet Communist leader Vladimir Lenin.

The Russia relationship was remarkable. The son of a Jewish Russian emigre to the US, the young Armand befriended Ludwig Martense, a Soviet agent in America, and in 1921 visited Russia, meeting Lenin.

In 1921, his then Allied Drug and Chemical Corporation made a deal with Soviet Russia, trading 1 million bushels of American grain for furs, caviar and valuables confiscated by the Bolsheviks. The deal would give Hammer the status of an “official friend” of the USSR.

During his life in the USSR, which spanned almost a decade, from the early 1920s to the early 1930s, he would amass many antiques, paintings and sculptures, including Faberge eggs that he bought basically for a few dollars only.

Apparently, the US expatriate press corps in Moscow called Hammer “the Politburo’s pimp”. And yet, the Russia relationship would span decades.

It has been said that “the most remarkable thing about Armand Hammer is that he created this personal empire largely by negotiating extraordinary deals with nations that have usually been hostile to the United States – and even more hostile to American capitalists”.

During the Reagan administration, one member of the president’s inner circle was reported as saying: “We simply don’t know which side of the fence Hammer is on.”

It was a trait that prevailed throughout his life.

In the 1996 book Paying For The Piper, the authors describe Hammer’s reaction to the unfolding disaster as being, “an elderly man apparently shocked by the events of the past 48 hours and shaken by the sight of bandaged men in the hospital wards”.

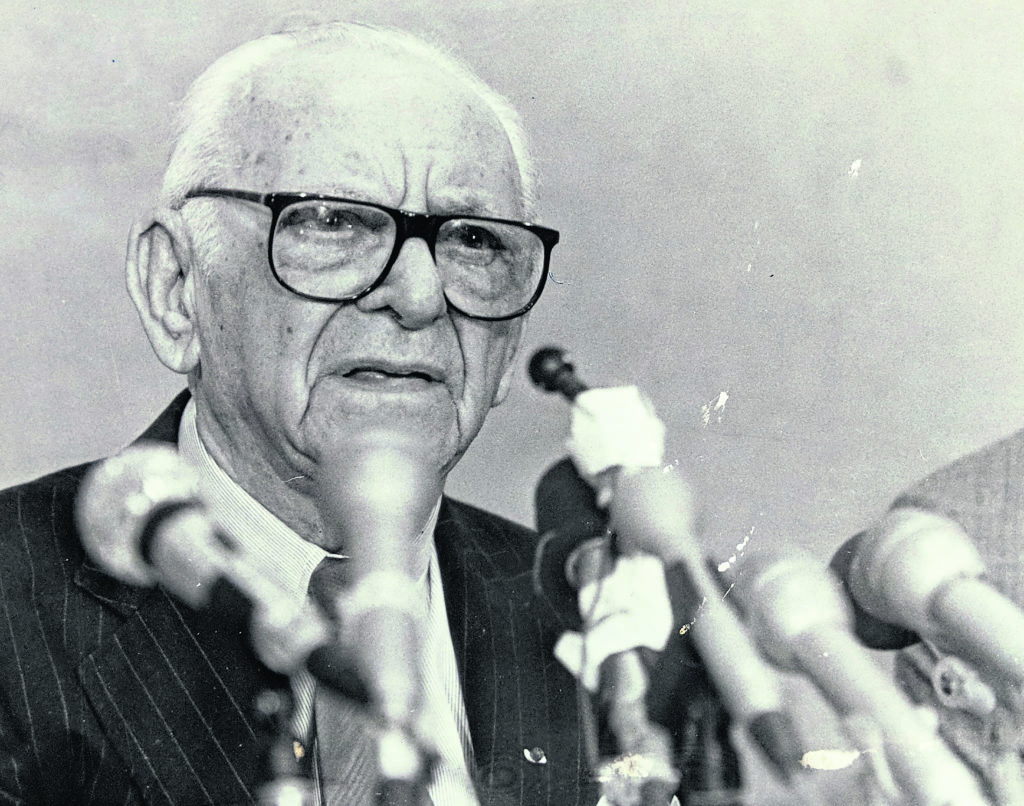

Hammer said at a press conference during his brief and only visit to Aberdeen: “I thought it was my duty to come here. I am the chief executive officer of the company and the buck stops at my desk. This is the greatest tragedy that ever happened in the oil industry in the world, and I thought it required my personal attention.”

Without admitting negligence, Hammer said that as operator of Piper Alpha, Oxy had a responsibility for clearing up the still-burning rig and for looking after its injured employees and the relatives of those who died.

However, the day after Piper blew up, he had taken tea with then UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher at 10 Downing Street.

On the 25th anniversary of the disaster, Ed Punchard, a diver and Piper survivor, was quoted in a Scottish newspaper as saying of Hammer: “It’s something I find rather odd, and I wouldn’t want to be misunderstood on this.

“If I compare the aftermath of Piper Alpha with the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon, the president of the United States, no less, was hauling BP over the coals, never mind the legal system, when you think how many billions of dollars they’d have paid out in compensation.

“The comparison is that Occidental chairman Armand Hammer got taken to tea by Margaret Thatcher at Number 10 the day after Piper Alpha.

“She walked out of No.10 almost hand-in-hand with him and stated what a wonderful man he was. I think her expression was ‘He’s a marvellous person, we have known him for many years. I’ve come into contact with him because he is very good to many, many charities’.”

Mr Punchard went on to write a book about his experience and followed it up with an award-winning film that was released to coincide with the tragedy’s 10th anniversary.

Hammer died aged 92 on December 10, 1990, a month after the Cullen Report was published.

And in 1992, the man who was Hammer’s closest confidante for at least the last 25 years of the magnate’s life, Carl Blumay, tried to blow the lid off the carefully crafted image of his late master.

The head of Occidental’s PR operation for more than two decades, Mr Blumay was once told by Hammer that his main job was “to make me immortal”.

He certainly worked assiduously to paint his employer in the best light and claimed to be unique in that he had never been obliged to sign a confidentiality agreement.

Mr Blumay must have been very angry for a long time to have written the way he did.

I received a review copy of The Dark Side Of Power, of which Mr Blumay was the lead author but supported by journalist Henry Edwards at the time of publication and found it compelling reading.

Somehow, it explained why Piper was a disaster waiting to happen and why survivors like Steve Rae found that the culture aboard the platform was “different”.

Mr Blumay portrays a man who on a personal level displayed few redeeming qualities, even though he was able to turn on the charm.

On the subject of Occidental, Mr Blumay points out that Hammer was in semi-retirement during the 1950s when he latched onto Occidental and, despite sailing dangerously close to the wind time and again, including coming close to disaster with Piper in 1984, Hammer broadly seemed to make it a success story.

While shamelessly pursuing a Nobel Peace Prize in his twilight years, Hammer was convicted of violations of US election law. He also faced constant accusations of wrongdoing by the IRS, SEC, and other government agencies.

Nor, by Mr Blumay’s account, was his client any bargain for members of the extended Hammer family, friends, and business associates, or for stockholders in Occidental, which he evidently treated as a private fiefdom despite it being a listed company.

That said, Hammer was awarded the US National medal of arts, was a professor emeritus of 25 universities, and was even nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, only losing to the Dalai Lama.

Despite the scale of the Piper disaster, Mr Blumay is perfunctory in his treatment of it; and perhaps one should not be surprised.

After all, he had for nearly a quarter of a century carefully managed Hammer’s persona, no doubt right down to scripting the “buck stops at my desk” remark made by his boss in Aberdeen, which he never visited again.

This is all he wrote about the disaster: “On July 6 (1988) a series of devastating explosions rocked Occidental’s Piper Alpha platform in the North Sea, shooting flames four hundred feet into the air, destroying the platform, killing 167 workers and putting the operation out of commission for an entire year.

Legendary oil well fighter Red Adair spent 23 days putting out the blaze.

“Armand took exactly the correct PR stance and did not soft-pedal the disaster. He went to Scotland immediately to make his presence felt. Many of the residents of

Aberdeen refused to comment on the disaster because they worked for Occidental and were in awe of Armand.

“An 11-month investigation produced a report for ‘unsafe practices’.

“Occidental made offers totalling $187million to the families of the 167 workers who died in the explosion.

“An out-of-court settlement was reached just three months after the disaster. With most of the settlement and reconstruction costs covered by insurance, Occidental’s losses were minimal.”

Regrettably, the UK authorities never threw the book at Armand Hammer; and I think the story that unfolds in The Dark Side Of Power tells us why.

To follow more of our special Piper Alpha 30th anniversary coverage, click here.

Recommended for you