RECENT months have produced two books about the North Sea that I can only describe as excellent. They’re very different and, in my view, of equal merit.

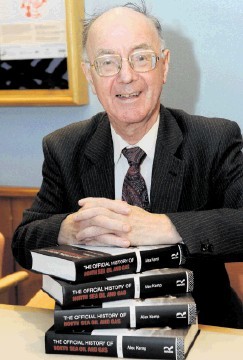

Dryly entitled the Official History of North Sea Oil and Gas by Professor Alex Kemp of Aberdeen University (publisher – Routledge) is a massive 1,300 pages covering the early political story of the UK continental shelf through to 1993.

The 300-page Sea of Lost Opportunity by Dr Norman Smith and published by Elsevier traces the story of the North Sea oil and gas supply chain to the present day and then looks ahead.

Both are intensively researched. Neither is a light read.

Prof Kemp writes in his capacity as the North Sea’s official historian and therefore had access to official archives.

Dr Smith writes from experience in the industry including as director-general of the long gone government creation . . . the Offshore Supplies Office.

The book stems directly from his PhD, which he successfully tackled in retirement. However, while Routledge carry a note about Prof Kemp’s distinguished career, Elsevier fails to do this for Dr Smith. That is a serious omission.

Official History of North Sea Oil and Gas

ONE of the striking early messages to emerge from the Kemp work is that successive UK governments have in fact bodged since the earliest days.

One discovers that, in the 1960s, the then Ministry of Power wanted to hark back to the UK 1934 Petroleum Act as a model for North Sea legislation. Observing how the important UK Continental Shelf Act of 1964 was drawn up, Kemp notes that “very heavy reliance was placed on amending and extending existing legislation”.

He writes: “While this is both understandable and consistent with the tradition of law-making in the UK, it remains surprising that the notion that petroleum exploitation offshore was fundamentally different in character from onshore activity was not considered to be strong enough to warrant a different legal framework.”

The Kemp book is an erudite journey that is full of surprises. For example, until I started to pick through the two volumes that comprise the official history, I did not realise, for example, that the First Licensing Round was complete before the boundaries of the UKCS with neighbouring countries had been determined.

I also hadn’t realised the importance and influence of Nato-related sensitivities when drawing the line between the UK and Norway. But then the so-called Cold War was raging.

And as one picks through the amply signposted pages with plenty of subheadings but sparsely relieved with maps, graphs and tables, though no photographs, it becomes abundantly clear that nothing about the North Sea story has ever been simple.

Prof Kemp has to be congratulated on the manner in which he has skilfully woven a highly complex tapestry that patiently tells the UK North Sea story through to 1993.

However, this is an uncompleted work.

It’s a pity that it was not possible to take the story through to 2000 at least. Over the coming year, Energy will dip into the Kemp volumes and relate at least a few of the events that have shaped the most successful and hugely valuable industry in Britain today.

The Sea of Lost Opportunity

TURNING to the Sea of Lost Opportunity, this book is highly relevant to the Britain of today . . . deeply stressed and seemingly unable to pull itself out of what has become an horrendous economic mire.

Just a few pages in, and one finds Dr Smith describing the decades-long downward spiral that characterised post-1945 Britain and which continues today. In essence, a strangely complacent place where waves of prosperity appear as brief and all-too thin veneers.

Dr Smith also reveals the political bodgings that come through so clearly in the Kemp book; and the almost desperation when it was realised that, beneath the North Sea, was a resource that might help restore the UK balance of payments.

However, the accent was on finding, grabbing and taxing the hydrocarbons prize. The supply chain came a poor second and it is the trials and tribulations that characterised the evolution of a UK and international offshore energy capability that are so ably dissected by Dr Smith.

One of the ironies is that Britain had a well-established supply industry before North Sea activity began, with companies like Burmah, then the smallest of the three UK majors, had placed export orders for £20million (over £320million in 2008 money) with British manufacturers. Contrast this with Norway, which had no prior upstream petroleum industry expertise at that time but in many ways has the upper-hand today.

Like the Kemp work, Energy will dip into Dr Smith’s analysis over the coming year as it is so relevant to where the UK supply chain is today and might be headed.

Might they make a good Christmas present? I’m not sure about that. Both cost more than pocket-money.

But I believe they’re a must-read for anyone who is hungry to learn about the industry that grew to become our greatest success story in a very long time.

Recommended for you