IT WAS in April 1990 that Graeme Coutts walked into Expro Group in Aberdeen “to do a favour in between jobs” for the base manager at that time, Glyn Williams, who today heads private equity firm Epi-v

At the end of July this year, Expro’s by then chairman retired from the company after more than two decades. The Coutts plan had been to help out for a few weeks.

“The reason was to look at Expro’s efforts in technology development which, at that time, were sub-standard. I had no intention of staying with the company. I came in, had a look, wrote a report and told them to shut it down,” Mr Coutts told Energy.

“They didn’t even look to be the type of company that could do technology development. I was bemused at the lack of strategy other than making statements that second best was good enough. To me that was unacceptable.”

Expro was then private equity-owned, had sales of around £40-50million and Shell was the biggest client.

According to Mr Coutts, it was Shell that also gave Expro its big break.

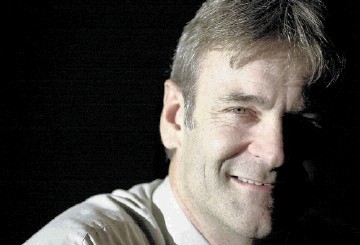

| Graeme Coutts Q & A: |

|---|

|

Age: 52 Education: Aberdeen Grammar and School of Hard Knocks Your career path: Started out in banking; jumped to oil & gas – Schumberger, Baker Hughes and then 21 years with Expro Group. Now an angel Hardest decision: Going against my father’s wishes by leaving banking for the oil industry Who do you admire in business? Chris Fay (formerly of Shell and a sometime chairman of Expro) . . . the sharpest guy I’ve ever had dealings with What do you regard as being your greatest success to date? Building Expro to a $4billion market cap company and selling it What do you do to relax? Work What is your favourite gadget? I love mechanical clocks What charity do you support? The effort to cure Alzheimer’s is really important to me Where would you like to retire to? Where I am . . . the north-east of Scotland |

“Shell announced an initiative called Drilling in the 90s, which was mostly an out-sourcing of services.

“Expro was a niche player . . . well testing and wirelining but no downhole tools, nor well perforating capability . . . not anything like the package they needed to complete the service offering needed by Shell.”

So Mr Coutts set about making sure Expro could offer the services that Shell needed.

“I invented for them, on the back of a cigarette package, a business called EGIS . . . Expro Group Integrated Services. The approach was not to provide everything standardised but to provide the best product for each well because all wells are different.

“That worked phenomenally for Shell and subsequently other companies like BP and Mobil. We ended up sweeping the board with integrated contracts. It was the making of Expro.”

CEO of the day was John Dawson. He was based in Reading but a regular in Aberdeen. To Mr Coutts, he was the “real hero of the business”. Not only did he lead a management buy-out, he took Expro to a stock market listing in 1995.

Graeme was by then well established in the company. Mr Dawson wanted him on the board.

“I was 36, knew nothing about what was required, had no idea why they had invited me onto the board and I tried to get off the thing twice because I didn’t understand what it was about . . . it was purely a financial shop at that time.

“I had left the financial world several years earlier. I would often turn up at work, hands covered in oil. I wanted to strip engines . . . do things like that. But my qualifications pushed me to something else.

“I suppose in many ways I had been very lucky. My early background I guess is quite interesting as I shouldn’t be here at all. A great number of people will say they suspect I was a mistake.

“Well I absolutely, categorically, was a mistake. My father was 60 when I was born and my mother was much younger. If fact she died last year aged 91 . . . an incredible woman. My father died in 1986, aged 86.

“When I came out of Aberdeen Grammar School there was no university for me. I was not given the option. I had to go and work to support the family. That has always set the tone for me. Everything has been a personal challenge. And I relish personal challenges and always have.

“So there I was; in 1995, on the board and no idea why they wanted me there. Little strategy was discussed.

“There was something underlying that wasn’t quite right about Expro. Although John was fantastic at leading the company, those surrounding him weren’t strong enough to help take the company where he would have liked to have taken it.”

But then Chris Fay, ex Shell, became chairman, a period of turmoil ensued, city analysts turned against Expro, John Dawson retired and Mr Coutts was asked to take over the reins.

“I spent the first day as the new CEO on the phone to investors telling them that they weren’t going to get their numbers (earnings expectations). And they weren’t going to get their numbers for a considerable period of time because I needed to re-engineer the business.

“I needed to put the horsepower and investment back into the critical components that would make Expro world class.

“That was 2003. Following the turmoil and profits warnings we then had a market capitalisation of about $150million.”

There was hostile approach to try and buy the business, to which the board said no. By late 2007, the business was storming along and worth $4billion.

Then the big bids for the company started.

“We had Halliburton, Goldman Sachs and Candover . . . they went after the business ferociously,” said Mr Coutts.

“My job at the time was very clear; make somebody pay far too much for the business. We pushed; the share price hit £15. After a tremendous struggle between Halliburton and Candover, which led to an action in the High Court in London, Halliburton was thrown out.

“We were duty bound to accept the Candover bid. The big shareholders in Expro made klondike returns. My job was easy; this was an easy company to run. But you know, having run the public company very hard and pushed it to the limit many times, at the point when Candover/Goldmans came through the door to buy the company, I was preparing to look at succession.

“That’s because I’m a great believer in the view that you do this sort of thing in five-year sprints, and then pass the baton on. But what happened is that they asked me to stay, having paid handsomely for the business.

“It might seem old-fashioned, strange honour, but I believe the buyer should always have delivered to him what he thinks he’s bought. So I stayed on the basis that I would mentor a replacement for me.”

But the first CEO replacement attempt didn’t work out and Mr Coutts had to return to the driving seat.

However, in August last year, Charles Woodburn stepped from Schlumberger into the Expro hot seat. It was job done.

By the summer just past, Mr Coutts decided it was time to depart Expro. But why not stay as chairman?

“While becoming chairman was a possibility, my view is that it is impossible for a former CEO to chair the company that he preciously led.”

Energy’s editor met Mr Coutts the day after he finished up as chairman. Still in his 50s, he was as sparky, passionate and unconventional as ever . . . looking forward to being an angel; helping promising small energy service businesses succeed.

But surely he will miss former senior colleagues?

“On a Friday afternoon, I used to wind them all up in my office; no agenda. I would take out a bottle of sherry and we would take a tiny glass. It was hilarious. I would ask what they had achieved during the week and what they had in mind for the coming week. And who do you need to get that done? What do you need me to do for you so you can achieve your objectives next week?

“I’ve never seen that in management books.”

Recommended for you