We have 12 years to clean up our carbon act on a global scale or face catastrophic climate change: that was the stark warning from the IPCC in October.

The following month, the UK Government reaffirmed its support for carbon capture and storage (CCS) – a tested technology that will deliver massive reductions in carbon emissions – and the Acorn CCS Project in north east Scotland secured a licence to select a suitable North Sea CO2 storage site.

We may be growing impatient for a more tangible CCS industry in the UK, but these developments cannot be underestimated: the UK Government ostensibly back on track with CCS; Crown Estate Scotland enabling development of CO2 transport and storage; and the Oil & Gas Authority working with government and industry to identify the infrastructure that can be re-used.

Earlier this year, the UK Government’s advisers on carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS), including experts from industry and academia, pointed to the role of CCUS clusters in bringing down costs. They laid out criteria for developing at least two such geographical groupings of industry by the mid 2020s, which would share transport and storage infrastructure.

However, the cost of delivering a CCS industry is just one part of the story, which has moved on since 2015 when the UK Government withdrew its £1 billion CCS Commercialisation Programme and pulled the rug from under the promising Peterhead CCS Project.

The concept of a just transition for fossil-fuel based economies is now growing in prominence. If this term is new to you, it means planning the move to a low-carbon future in a fair and progressive way. It recognises that we can capitalise on the oil and gas industry skills, workforces and infrastructure we already have while developing new ones. It also depends on building vibrant and resilient communities and being aware of the major concerns and challenges for industries as they decarbonise.

This definition derives from the work of Dr Leslie Mabon, at Robert Gordon University, who we are working alongside on ACT Acorn, an EU-funded project that will contribute to moving the wider Acorn project towards completion by the 2020s.

Scotland’s Just Transition Commission was established in September, chaired by Professor Jim Skea, with a remit to “maximise opportunities of decarbonisation, in terms of fair work and tackling inequalities, while delivering a sustainable and inclusive labour market”.

The concept is supported by research from the New Economics Foundation and Institute for Public Policy Research, and by trade unions and NGOs through the Just Transition Partnership. At the same time, groups as diverse as WWF and Oil and Gas UK have begun calling for clearer government policy and support for CCS.

Some industries and sectors will be hit by the need to decarbonise, while others emerge and grow. Any industrial strategy should take this into account and ensure that jobs and skills from the former can be transferred to the latter. A just transition will not happen on its own, and the collapse of an industry can have ramifications far beyond job losses.

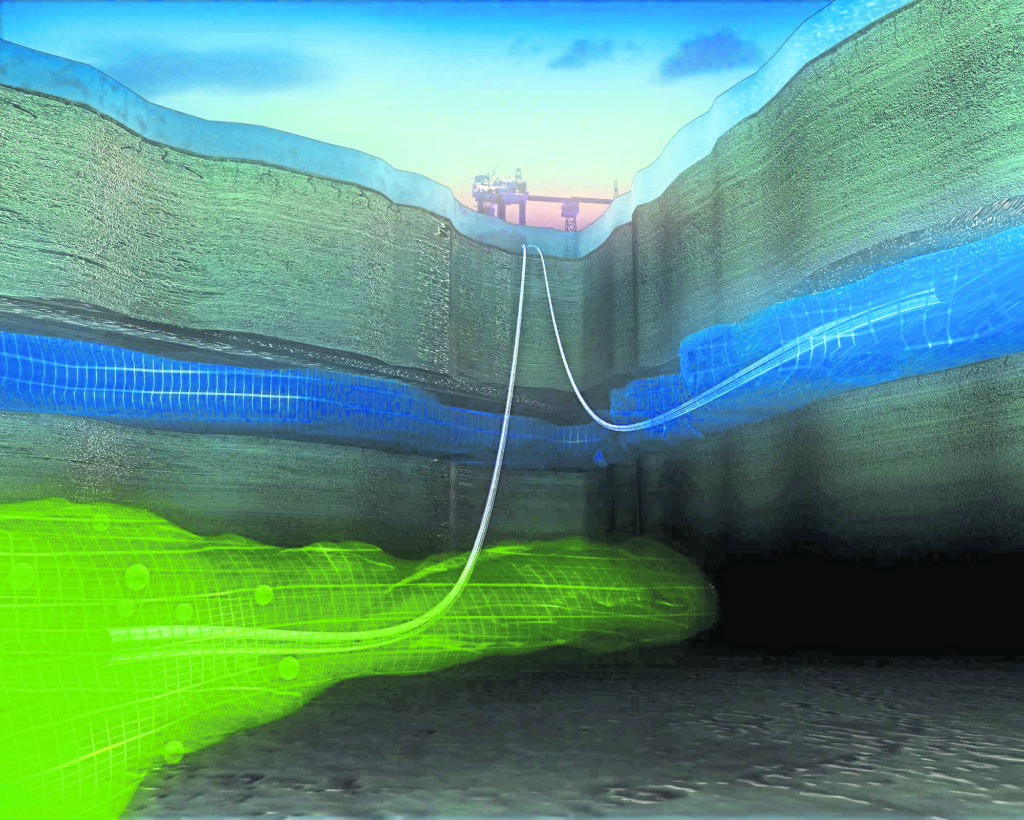

What will happen to offshore oil and gas sector workers when hydrocarbon production ceases? CCS offers a neat fit, using the same people to carry out the same process, only in reverse: injecting liquefied CO2 into the same geological formations deep below the seabed, which have securely held oil and gas. The technology has been operating in the US and Norway since the 1990s.

Industries that need fossils fuels for large amounts of heat, and those that produce CO₂ as part of their process, will also face the possibility of collapse or relocation overseas if they fail to decarbonise. Providing the infrastructure to transport and store CO₂ means that jobs in these industries can be retained. And it encourages new high-emitting industries to site themselves in the area, creating zero-carbon zones with a competitive advantage. In the move towards 100% renewable energy, these technologies use materials that must also be decarbonised.

On the trajectory to a fossil-fuel free world, North Sea methane can provide low-carbon hydrogen for heat and transport, if produced by steam methane reforming alongside CCS. That means jobs emerging as the hydrogen economy grows and develops. Look to Aberdeen where hydrogen is already used in public transport and may soon be rolled out to provide heat using the existing gas distribution network.

Economies across the world face the task of tackling climate change while supporting society in terms of growth and jobs. There is growing recognition that CCS is not just the least-cost way to achieve deep decarbonisation – it also has a key role in protecting jobs and enabling a just transition from a carbon-intensive economy to a low-carbon future.

The Paris Agreement urges the creation of “decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities”. The UK Government’s focus on the development of CCUS clusters in the early 2020s begins to address these priorities as well as the imperative of climate action. We will be doing all we can in 2019 to ensure this momentum continues.

Rebecca Bell, Policy & Research Officer, Scottish Carbon Capture & Storage

Recommended for you