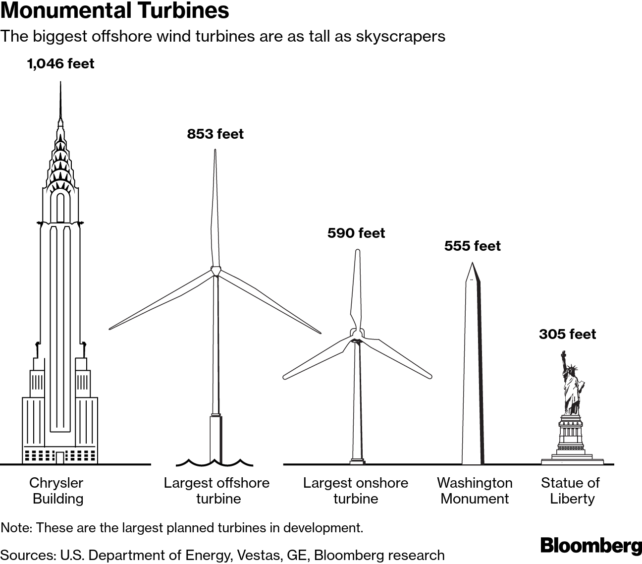

How do you install a wind turbine almost the size of the Chrysler building in the open ocean? Just get a boat with deck space larger than a football field and a crane that can lift the weight of 1,100 Chevy Suburban SUVs.

Those specialist ships are scarce, numbering about a dozen in the world. And at a cost of more than $300 million, they each need to be capable of hoisting generators the size of shipping containers atop steel towers hundreds of feet tall.

While wind turbine manufacturers led by MHI Vestas Offshore Wind A/S and General Electric Co. are expanding the size of their machines quickly, the small cadre of mainly closely-held specialist shipowners that does the installations is hesitant to build more ships before they know how big the vessels need to be. That indicates a looming ship shortage in the next decade, threatening the outlook for a seven-fold jump in offshore wind capacity by 2030.

“The installation companies will have to adapt to meet expected demand,” said Michael Simmelsgaard, head of offshore wind at Vattenfall AB, a utility with projects from Britain to Scandinavia. “We will see ships entering the market that were not originally used for turbines, but for offshore oil and gas.”

Those ship owners include Deme Group, controlled by Belgian engineering company Compagnie d’Entreprises, or CFE, and Jan De Nul Group, based in Luxembourg. Both are building new ships. But for now, analysts say the industry have underestimated the challenge faced by ever-larger machines.

That concern doesn’t seem to register with the ambitions of renewable energy developers. Europe’s biggest utilities are investing more than $10 billion this year alone on getting electricity from sea breezes. BloombergNEF expects offshore wind capacity to jump to 154 gigawatts by the end of the next decade from about 22 gigawatts now as the thirst for cleaner electricity grows. Most offshore wind farms are in northwest Europe, but China, the U.S., and South Korea will be big markets in the future.

Installing turbines is a feat of engineering. First, foundations weighing hundreds of tons are rammed or anchored into to the seabed at depths of 50 meters or more. Then, a massive crane hoists steel towers each the size of a small skyscraper on to the footings. Finally, the generator housing, or nacelle, is perched on top and the blades are put in place. Those nacelles already are about the size of a truck.

The few ships designed to do this are almost exclusively in Europe, and some are booked up until next year. Owners can charge anything from $112,000 to $180,000 a day for their services. That compares with the below $25,000 rate for one very large crude carrier class supertanker.

To squeeze more energy out of the wind, manufacturers like MHI Vestas are building bigger machines with longer blades and more powerful nacelles. The next generation of turbines will need even bigger boats.

One of them is Jan De Nul’s Voltaire, named after the French writer, that starts service in 2022. With a length of 169 meters (554 feet), it has deck space bigger than the soccer pitch at London’s Wembley Stadium. Built in China, the ship will be able to carry 3,000 tons of equipment to a height of 165 meters. That’s twice the load of Jan de Nul’s Vole Au Vent ship built six years ago and more than enough to hoist the largest turbines currently available.

“We recognize the global trend toward larger wind turbines for increased green energy demand,” said Philippe Hutse, offshore director at Jan De Nul. “The Voltaire will have all the required specifications to meet the upcoming challenges.”

Deme Group’s new vessel will be ready for installations next year. At over 215 meters long, its crane will be able to lift 5,000 tons to a height of more than 170 meters.

Nevertheless, a shortage of ships could come as early as 2022 since the European market is expanding at an “unprecedented pace,” according to Clarksons Platou AS, a broker that has arranged offshore wind charters for a decade. The squeeze will only get tighter as boats leave the region for growing markets in Asia and the U.S.

“Some of the current vessels can be upgraded to serve the new turbines to a certain extent,” said Jens Egenberg, an analyst at Clarksons Platou in Oslo. “But this is not nearly enough to meet the demand for installing the larger turbines.”

But the wind industry has survived challenges in the past. Decades ago, with turbines still in their infancy, there weren’t enough specialist cranes to erect them. And about 10 years ago, costs were rising fast and offshore wind farms got delayed because there weren’t enough installation vessels. Offshore wind was deemed “a niche” by the then head of Vestas Wind Systems A/S, Ditlev Engel.

Generator sizes have multiplied over the decades, from the half-megawatt units used in the first offshore wind farm built in 1991 off the Danish coast to the 12-megawatt giants currently planned by General Electric Co. Vestas Chairman Bert Nordberg said last month that a single generator could be as big as 20 megawatts in the future.

The first prototype of GE’s biggest model will be installed on land for testing at the Port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands, John Lavelle, chief executive officer of the company’s offshore wind unit, said in an interview. He’s already started offering the turbine in Europe and the U.S. for deliveries from 2021.

That gamble on future turbine size is precisely what’s occupying the thoughts of shipping executives. Anyone building a new installation vessel will be looking at a life of at least 20 years, said Even Larsen, chief executive officer at Fred Olsen Ocean AS in Oslo.

His company has three such jack-up ships—so called because of their long support legs that can be lowered to the seafloor—and may invest in more. His dilemma is how big to make the next ships. Build too small and you won’t get the job. Build too big and the economics won’t stack up. Larsen said vessel owners are waiting to see what the others are doing.

“It has been a challenge to define the required characteristics of a potential new build due to the rapid development in the turbine size,” Larsen said. “It’s important to hit the target with a new vessel design.”

As many as 18 nations will have offshore turbines by 2027, compared with seven in 2017, according to industry consultant Wood Mackenzie Ltd. Wind provided less than 1 percent of the world’s power in 2006, but BNEF estimates that will rise to 24 percent by 2040.

And while numbers like those would be great for the environment, as well as turbine makers and utilities, they show the challenges facing the installation market. In a sign of what’s to come, ship operator Seajacks Ltd.’s Seajacks Zaratan, built specifically for the harsh conditions of the North Sea, is leaving the main European market to install turbines in the Taiwan Strait this year.

About 10 of the current installation vessels were built five to seven years ago and almost all of them have gone through some upgrades, according to Soren Lassen, senior offshore wind analyst at Wood Mackenzie’s power and renewables division. As a result, he expects to see more vessels from the oil and gas industry being adapted for offshore wind, especially to install foundations.

The cost to hire a ship is also as much as 30 percent lower than it was earlier this decade because of an oversupply. That’s putting even more pressure on getting it right and the need for a higher utilization rate to make a profit.

“The pressure on rates has been quite dramatic,” said Larsen at Fred Olsen. “At these rates, it’s difficult to secure a good business case for a new build.”

While there are enough ships to serve the industry for now, BNEF analyst Tom Harries in London sees a crunch in about four to five years.

“You’ll very quickly run out of boats that will be big enough to lift the next generation of turbines,” he said. “The vessel owners have underestimated the size and now everyone is waiting to see who will move first.”

Recommended for you