AT LEAST Ofgem delivered on one promise – that it would publish the findings of its catchily-named TransmiT exercise before Christmas and indeed it came as a gift-wrapped package for the onshore wind industry.

Having committed to the Beauly-Denny line it would be irrational, even by Ofgem’s standards, not to ensure that there is a justification for it in terms of electricity to transport. That is why the proposed cost of carrying power from the Highlands to markets in the south has been slashed.

It was economic to build windfarms in the north of Scotland prior to these recommendations and it will be a lot more profitable now, with the rate per megawatt hour down from £26 to £10.

So look forward (or perhaps not) to many more onshore windfarm proposals and a powerful political imperative for local authorities and Holyrood to consent them to meet targets.

This is because onshore wind is still the only serious game in town. Significant offshore remains a dream.

The more serious option over the next decade for diversification of renewable generation north of the central belt would be for much of it to come from the Western Isles and Shetland where there are big proposals for windfarms which are both onshore and offshore, if you see what I mean. They are in a third category. The size of land-based turbines and costs of installation and maintenance would be par for the industry, so no complications there.

But the islands are offshore in the sense that new subsea cables are required to export power to market. Hence both onshore and offshore.

However, this is the prospect that has been dealt the harshest blow by the Ofgem recommendations.

The prospective charge, based on Ofgem’s modeling, would be £77 per megawatt hour – a full £67 more than on the nearest mainland. And on that basis, little may happen.

So the question that has been around for a decade now presents itself in stark form: does anyone in authority want renewable energy developments to happen in the Western Isles, Orkney and Shetland or the waters that surround them?

And does anyone in political power in Whitehall or Holyrood care enough to do anything about it?

Essentially, Ofgem has done what the “big six” electricity generators wanted – and remember these include SSE and Scottish Power. The regulator has given considerable benefits to developments on the mainland and basically rejected the case that it should enable island-based projects.

So where do we go now?

Well, there is a consultation period until the end of February though the Ofgem report has the feel of finality rather than of being interested in further discussion of what is an issue of principle.

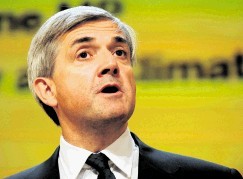

If Ofgem stands firm, there are two other possible solutions. First, it is open to the Secretary of State, Chris Huhne, under the Energy Act of 2004, to over-rule Ofgem and put in place a charging regime for the islands that will remove obstruction to renewables development.

Second, though it has kept very quiet, Holyrood can provide its own solution from a different direction.

The banding of ROCs – renewable energy subsidies – is devolved to Edinburgh and already there are significant variations from what is on offer in the rest of the UK.

By creating an additional band for remote island generation, the Scottish Government could compensate for the additional transmission costs. Problem solved.

In reality, a pure “postage stamp” system has never been a serious option and even I would not advocate it. Transporting electricity from one end of the country to the other is costly and transmission losses are significant.

Comparisons with transmission costs in the populous south of England are irrelevant and unhelpful.

The focus must be the huge gap between the cost of generating electricity on the Highland mainland and the proposed charges for the three island groups.

These are discriminatory and, in my view, illegal under the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive. It says islands and peripheral areas must not be penalised in this way.

They are also self-defeating in terms of renewables generation and carbon reduction targets.

Now is the time for London and Holyrood to act in the interests of what these islands can deliver or else have their fine words about renewables “potential” judged accordingly.

Recommended for you