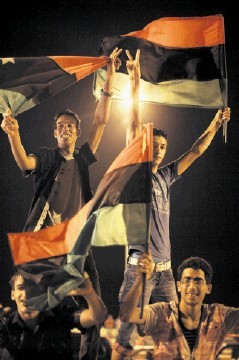

THE Arab Spring has caused massive upheaval in one of the world’s most strategic oil producing regions.

The impact, however, has varied from country to country, depending on a myriad of internal social and political factors.

Demonstrations began in Tunisia following the self-immolation of street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi after police confiscated his cart-stall and harassed him in public.

Protestors sympathetic to his plight began to express their anger at poverty levels and high unemployment, with gatherings soon forming in the capital, Tunis.

Many called for the resignation of then president Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, and within 28 days of Bouazizi’s self-immolation, he had fled the country.

Demonstrations then spread to Egypt, and within 18 days President Mubarak had also been forced to step down.

While the Tunisian revolution was a game-changer, the Egyptian revolution sent shockwaves throughout the region, awakening long-standing grievances among Arab populations.

Demonstrations intensified in Bahrain, Jordan and Yemen, while in Libya military units defected to create a state of civil war.

In a number of other strategically important countries, including Saudi Arabia, Oman, Algeria and Morocco, lower level unrest led to talk of a domino effect, but the response of these governments, which involved concessions, pay-outs and repression, highlighted the importance each case.

So what was the impact on the upstream oil and gas industry?

In Egypt, the complete collapse of authority lasted only a few days, and levels of production remained constant at around 700,000barrels per day (bpd).

Unrest was largely concentrated in urban areas, and although a number of the main ports were temporarily closed, the effects on transportation were relatively minimal in comparison to other nations.

However, the impact has become more keenly felt in the aftermath.

There have been five attacks on a strategically important gas pipeline to Israel and Jordan, while instability has deterred tourists and foreign investors, exacerbating fiscal shortages and leaving foreign operators unpaid for the oil and gas they have produced.

Uncertainty over the economy and the government’s ability to pay for production is expected to endure as long as the political environment remains uncertain.

In Bahrain, the unrest had a minimal effect on the country’s oil industry and production rates remained constant.

However, the manner of the government’s brutal crackdown and the deployment of a Saudi-led security force to the country created massive resentment among the majority Shi’ah population, who have long expressed resentment towards their Sunni rulers.

In Libya, the conflict between rebel fighters and pro-Gaddafi forces has had a much more profound effect. Foreign companies evacuated their staff in February following a rapid deterioration in the security environment and oil production declined by as much as 1.2million bpd.

With fighting ongoing it is uncertain when foreign operators will return to the country.

Syria and Yemen have seen attacks targeting oil pipelines. Given that prospects for security remain bleak, further attacks and disruption should be expected.

At the time of writing, no sanctions had been imposed on the Syrian energy industry, but the US has threatened to target the sector if the government’s brutal crackdown continues.

All of the above makes for grim reading, but a number of the region’s most important oil producers have escaped significant unrest.

In Algeria, recent memories of violent unrest have dampened calls for revolution. The current president is also credited with helping improve conditions, so calls for a regime overthrow have been muted.

Eastern Saudi Arabia has seen some demonstrations, but the security forces remain capable of containing unrest.

Even Iraq has avoided fallout from the instability.

The Middle East will remain one of the most important oil producing regions in the world, but foreign operators must assess and prepare for the main security and political risks presented by instability.

Intelligence-led risk assessments, training and crisis management should all be in place so staff can react quickly and correctly should conditions deteriorate.

Evacuation plans should also be in place, and should not rely on air evacuation alone. The closure of Libyan airspace demonstrated that a variety of exit routes should be kept in mind.

The Middle East will remain a major source of opportunity, but only for companies with proper risk mitigation procedures in place. With sufficient preparation companies can avoid being caught off guard, as so many were when events unfolded rapidly in January.

Alan Fraser and John Drake are Middle East specialists at security consultancy AKE

Recommended for you