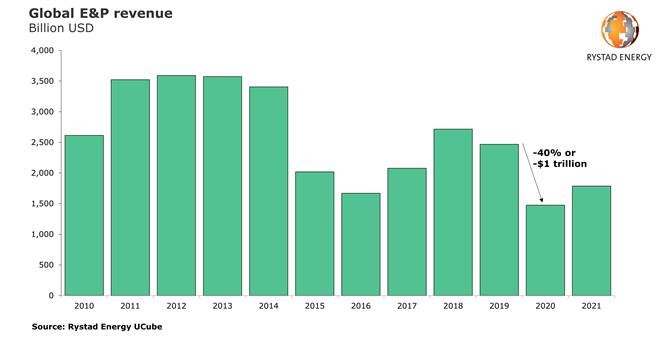

The devastating effect of the Covid-19 pandemic on global oil and gas exploration and production (E&P) companies is better understood by looking at the industry’s expected total annual revenues for 2020.

A Rystad Energy analysis shows that global E&P revenues are now forecasted to fall by about $1 trillion in 2020, a drop of 40% to $1.47 trillion from last year’s $2.47 trillion.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, Rystad Energy expected total E&P revenues to reach $2.35 trillion in 2020 and $2.52 trillion in 2021. Now 2021 revenues are also projected lower, at $1.79 trillion.

Companies’ cash flow is also set to plunge. For 2020 we estimate free cash flow for the E&P sector will shrink to $141 billion, or one-third of what it was in 2019. This is based on our base-case oil price scenario of $34 per barrel in 2020 and $44 per barrel in 2021, so there is a considerable downside risk if the current low-level prices persist.

“This drop not only undermines the companies’ solidity and reduces money available for investments and dividends, but also significantly cuts government tax revenue. It will be challenging for petro-states such as Russia and many Middle Eastern countries to sustain their budgets,“ says Rystad Energy’s upstream analyst Olga Savenkova.

In the short term, national wealth funds might come to the rescue and plug holes in the budgets to avoid sweeping spending cuts, but if the low-price environment persists these countries could come under serious financial stress, adds Savenkova.

Initially, Rystad Energy expected upstream spending to fall about 20% this year as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, which would have reduced investments by $100 billion from the 2019 level. As companies have continued to crimp investments, we now expect upstream spending to fall by 25% instead, from $530 billion in 2019 to $410 billion this year.

US shale remains the largest contributor with reported plans to slash 38% off their previously announced 2020 capital budgets, which implies a cut of nearly 42% compared to 2019 spending. These record numbers are followed by oil sands producers, which have also revised down spending by 42%. Conventional supply segments show cuts in the range of 19% for onshore to 12% for offshore deepwater assets, as these segments are not as flexible when it comes to managing their capital costs.

The capex cuts will have a particularly strong impact on discoveries and companies’ ability to proceed with final investment decisions (FIDs) on new projects. This year might be marked by the lowest project sanctioning activity since the 1950s in terms of total sanctioned investments, dropping to $110 billion, or less than one-quarter of the 2019 level, with most of the projects being deferred.

An operator may need several years to bring a deferred project back on track as more strict economic requirements are applied for a new FID. Facing the threat of prolonged low oil prices, stakeholders are likely to lower projects’ breakeven price requirement, which was already on average below $35 per barrel even before the crisis. This will send many developments on a long-lasting cost optimization journey.

But, in contrast to the previous downturn, this time the situation is complicated by the distressed position of many service companies. The oilfield service sector already made substantial improvements in the supply chain with significant cost reductions back in 2015–2016, and operators cannot rely on a repeat performance a second time around.

Operators are now understandably demonstrating extreme caution when it comes to future investment commitments, resulting in a drop in sanctioning as projects are reshaped and paused until oil prices recover. Considering the high maturity of most oil-producing regions, this approach to handle the crisis puts huge volumes of unsanctioned production at risk, potentially undermining medium-term liquids production levels.

At the same time, we see a growing decarbonization sentiment from both E&P players and investment banks, with major players targeting to reach carbon neutrality. As a result, the current low appetite for new project sanctioning could mean “peak oil” will arrive sooner than what we thought only a few months ago.