Floating offshore wind turbines are the technological growth area for the offshore wind industry. Though the first industrial scale prototype was built in 2009, floating offshore wind (FLOW) is rapidly moving towards large-scale commercialisation.

Many forecasts suggest there will be a fleet as large as 15 GW by 2030. Floating wind farms could provide up to 15% of the global offshore wind installed capacity by 2050.

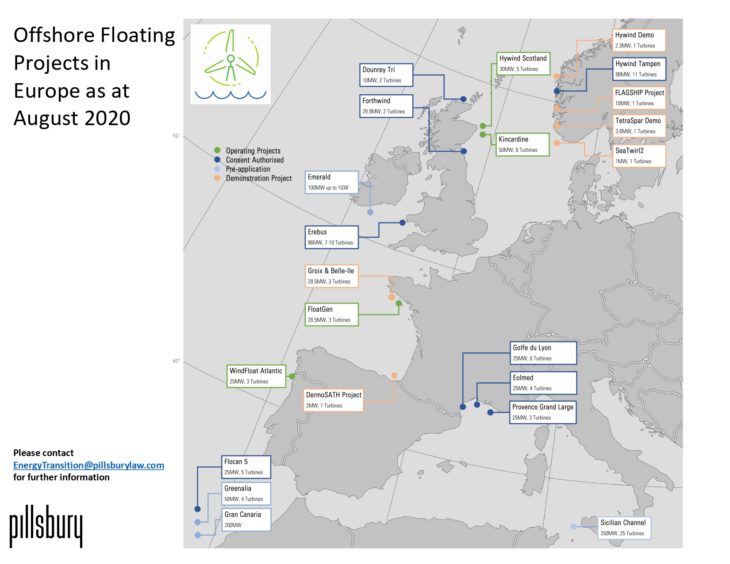

Demonstrations of FLOW have been developed across Europe with various technology types. There have been proof of concept developments with one turbine only, to three-turbine pilots, like the FloatGen Demonstration project in France.

Larger projects, like Hywind Scotland (operating since 2017) with five turbines, and Hywind Tampen in Norway with 11 turbines (expected to complete construction in 2022), also exist. The size of floating wind farms in Europe is growing too, with the 7 Seas Med project in the Sicilian channel, which requested government authorisation in early July 2020, intended to produce 500 MW.

The size of commercial floating wind farms further afield is also growing. Eolfi Greater China has been developing a portfolio of five 500 MW projects off the Taiwanese coast and there are two similar sized projects being developed off the coast of Ulsan in South Korea. The future of offshore wind, it would seem, is floating.

Zero-subsidy

The cost of offshore fixed bottom windfarms has been, and is still, decreasing. It is expected that windfarms could generate electricity more cheaply than existing gas-fired power stations as early as 2023. Projects due to become operational are doing so at prices below the reference price that the UK government is expecting to be the price of electricity on the open market in the relevant year.

In Germany and the Netherlands, the first auctions have been won with zero-subsidy bids and more than 2.5 GW of zero-subsidy capacity has been bid into the European offshore markets. This does not mean that all projects will be zero-subsidy, but it does go together with the decreased costs of the technology.

This contrasts to the position for FLOW. There the value of subsidies that can be obtained remains uncertain in most jurisdictions and the technology is not yet sufficiently developed to be standardised.

While there are four main design types (barge, semi-submersible, spar, tension-leg platform), there are also proposals for two turbines on a single platform. This diversity in technology reduces supply chain optimisations and economies of scale.

Incentives are key

Many of the European demonstrators have received national or international funding, much of which is being provided by the European Union.

Indeed, the EU is actively supporting floating wind energy systems for deeper waters as they see this as improving the European position in the global market. Funding is available for demonstration projects, pre-commercial deployment and commercial deployment.

One example of such funding is the grant by the EU of NOK 290 million to a consortium led by Iberdrola in April 2020, for a FLOW turbine at the test centre at Karmøy. The consortium members may also be able to access further grant money from the EU once they land the final agreement.

The continued availability of subsidies will likely determine how competitive the market will be in future.

UK subsidies

In the UK, particularly in the context of Brexit when EU funding may no longer be available, the key question is whether the next round of contracts for difference (CfD) auctions will have a separate pot for floating and fixed offshore turbines. This would give FLOW its own administrative strike price.

A consultation on this matter by the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) closed for comments on May 29, 2020, and the date for publication of the consultation response remains unknown. If the consultation is successful, the new “pots” would apply from 2021.

It would be a mistake not to separate the pots for fixed bottom offshore wind and FLOW, as:

- the economics for both types of project are different;

- significantly higher levels of deployment of renewable energy projects are needed to meet the UK’s plan for net zero in 2050;

- prioritising FLOW will help maintain a position as industry leaders in the UK;

- enhancing bankability for projects and liquidity of investment into FLOW projects through the availability of a competitively priced CfD will facilitate debt availability at more attractive pricing.

Not all plain sailing

Making subsidies available is not the only challenge to circumvent prior to building large commercial scale FLOW farms across Europe.

In many European jurisdictions, legislation is needed in order to facilitate the next step towards developing FLOW projects. Whether this is to allow for competitive tendering; to allow for a systematic grant of seabed leases; or to update centralised economic rules to ensure that incentives can be given to developers.

There are also commercial considerations, such as ensuring that there is a clear offtake solution available and that any required port infrastructure is developed so as to create the logistical hubs necessary to support FLOW. In some cases this includes the opportunity to review the fortunes of ports that have served the oil and gas industry for decades but now face a more uncertain future.

The UK remains well placed for large-scale commercialisation of FLOW, with clear existing rules as well as a roadmap for FLOW development. Clarity on the incentives that will be available at the next auction for CfDs will only help further.

Recommended for you