The hydrocarbons landscape is going through dramatic changes and worries over peak oil appear to have been pushed to one side for now.

Indeed, with the US on the brink of gas self-sufficiency thanks to the shale revolution, with LNG exports just around the corner and with domestic oil production rising for the first time in many years, again thanks to shale, plus massive resources being identified worldwide, here, there and just about everywhere, it is clear that the energy book must be rewritten.

This is surely reinforced by what appears to be a staggeringly large oil reserves base in Kurdistan, very large conventional gas discoveries being made in East Africa and the now clear emergence of the Falklands as a new energy province.

Let’s stick with shale.

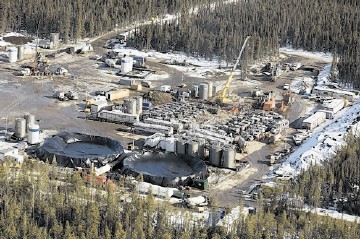

Just in the last few weeks, Apache Corporation has discovered an enormous shale gas field containing up to 48trillion cu ft of recoverable natural gas in northeastern British Columbia, Canada, from reserves of 210TCF of gas in place.

The company’s vice-president for worldwide exploration, John Bedingfield, said: “This is probably the best shale gas reservoir in the world.”

In Turkey, Anatolia Energy has obtained an independent assessment of its unconventional resource on its Dadas shale from Ryder Scott Petroleum Consultants. The company has stated that the P50 gross best estimate is of 11.6billion barrels of original oil in place at Dadas on the Bismil, Antep, and Sinan blocks.

ExxonMobil and Rosneft have joined forces to assess the potential for apparently huge oil shale reserves in Western Siberia.

This agreement provides for ExxonMobil to assist Rosneft in the evaluation of tight oil in Western Siberia and for Rosneft to farm into some of its tight oil projects in Canada and Texas.

Exxon is considering shale opportunities in China too where it could have as big an impact as it has had in the US, or at least that is an increasingly held view.

However, Edinburgh analysts Wood MacKenzie are more sceptical than some and, at last month’s World Gas Conference (WGC), delegates were warned that developing a sizeable domestic Chinese production profile will take longer to build than promoters would like.

That said, WoodMac sees shale resources in the Sichuan and Tarim basins as making a substantial contribution to China’s energy needs by 2030. On the other hand, demand is set to rocket four-fold over the same period and this most populous of nations is forecast to make up almost 30% of global incremental gas demand growth within the timeframe.

Although the Chinese government has ambitious shale gas targets for 2020, Wood Mackenzie believes production will be delayed due to a range of challenges, including a need for deeper geological understanding of China’s shale potential and know-how to exploit this.

In Europe, the situation is a lot less clear and the fact that Exxon has just called a halt to its shale gas exploration programme in Poland will be viewed as worrying by various other holders of shale gas exploration licences. In Austria, OMV put the brakes on its intended shale campaign in the spring, pending clarification of the country’s regulatory regime.

Basically, the European programme is very immature, with most if not all member states currently aspiring to develop shale-based oil and gas resources at sixes and sevens over how to regulate.

The same can be said for the European Commission in Brussels where officials appear to be struggling to get to grips with how to sensibly regulate an emerging industry that is so new that there is as yet no commercial production of shale gas.

For the time being at least, different countries are taking different approaches, not least in the UK where Energy is given to understand that the Government currently places, at best, little strategic value on shale gas (or indeed oil) as a part of the future energy mix of these islands, though coal-bed methane at least has the nod through the Government’s revised gas-fired power generation strategy (er … second dash for gas).

Aside from renewables, there is far greater interest in nuclear, despite the economics of the madhouse that go with and the need to apply hidden subsidies to underpin both current operations and future-potential new generation plant investment and operation.

To my way of thinking, that is a serious mistake, not least because the UK political machine’s apparent current unwillingness to underpin shale exploration as an onshore strategic priority means that companies wishing to explore for and exploit such resource will face potentially unsurmountable opposition from local and vested interests . . . in some cases quite possibly the very same people currently fighting against windfarm projects in many parts of Britain.

With the not-always-appreciated or understood (by government) UK North Sea in rapid and irreversible decline (barring a miracle of the kind that blessed Norway some months ago with the linked Aldous/Alvadsnes oil discoveries), our imports of both oil and gas are climbing.

We foolishly comfort ourselves by thinking that neighbour Norway will plug at least the piped gas gap; that, plus imports of LNG (liquefied natural gas), from who knows where.

Day by day, we’re increasingly a ship of fools, pushing our credit beyond the limit and becoming ever more unwilling to exploit the resources we have beneath our feet for all sorts of reasons.

Meanwhile, every month onshore, massive new unconventional hydrocarbon resources . . . especially shale-based . . . are coming to light around the globe and I’m not at all sure that we, the UK, are a part of that.