Secrecy surrounds the UK Government’s £1billion competition to decide who will lead the country’s drive to prove that carbon capture and storage (CCS) can work.

The stakes are high, with the technology seen not only as crucial in the battle to cut harmful carbon emissions and tackle climate change, but also in enabling local firms to tap into a burgeoning, multibillion-pound global market.

Shell and SSE hope their joint scheme at Peterhead’s gas-fired power station will get ministers’ backing when the winners of the contest are revealed in the autumn.

But few details are known about the proposal, because Westminster’s department for energy and climate change (Decc) has banned bidders from discussing their plans publicly.

A glimpse of what may be involved can be found in Canada, however, where there was a major breakthrough in CCS development last week.

Shell and its partners announced that they were ready to go ahead with the world’s first CCS project for an oil sands operation.

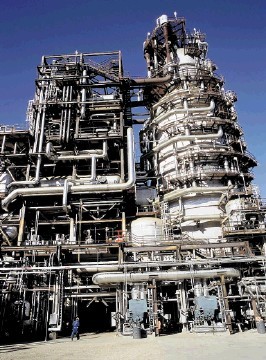

Energy production at the oil sands in the province of Alberta is often criticised for its environmental impact. But from late 2015, Shell’s Quest project intends to capture more than 1million tonnes of the CO2 produced during bitumen processing and store the emissions deep underground.

The initiative will cut about a third of the emissions from the plant – the equivalent of taking about 175,000 cars off the road every year.

Bill Spence, head of CCS at Shell, told the Press and Journal the Quest project was “comparable” in scale to the plans for Peter-head.

Quest also offers an illustration of the amount of public funding potentially required for Peterhead’s CCS scheme to get off the ground.

The provincial government in Alberta – which has population smaller than Scotland, at about 3.645million – is contributing £476million. In addition, the national government of Canada will invest about £76million.

Up to 700 workers will be employed during the construction phase, expected to take about 30 months.

“This is one of about half a dozen projects in the world to prove to the public that it works,” said Mr Spence. “It is one of four projects that we are pursuing.”

As well as Alberta, Shell has a scheme up and running in Norway to develop capture technologies, and one in Australia involving contaminated gas.

“The fourth one is our submission to the Decc competition,” Mr Spence said. “We hope to hear back soon from the UK Government.”

He believes the Peterhead project would “essentially be the first of a kind”, because of the use of a depleted North Sea gas reservoir to store the carbon after it is captured.

Mr Spence is confident such technology — once proven commercially — will be in demand across the world.

“I think there are many people looking to use that (technology),” he said.

Experiences in Alberta, Norway and Australia could influence the Peterhead project, and vice versa, he added.

“When you look at these projects there is a real willingness to share learnings. One of the key things is that our knowledge is made available for other people.”

Recommended for you