I have met the events of recent weeks in North Africa with great interest and a large degree of disheartenment. As former senior intelligence analyst for the Middle East & North Africa (MENA) region, assessing these kinds of attacks was part of my daily work.

Today, my role is to work with companies, highlighting the huge benefits of risk mitigation strategies, training, and the knowledge to secure personnel operational in challenging environments.

What I have found particularly interesting is the widespread perception, including at the highest levels, that this threat is new, and that the scale and capability of insurgents has radically increased.

However, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), as it is known now, has been active in Algeria and the wider region for many years. In fact, in 2004-2006, I analysed numerous attacks, targeting energy personnel and assets in Algeria – and on at least one occasion did so in this very column.

Enlisting the expertise of my colleague from our intelligence team, Alan Fraser, not least to present at the recent Aberdeen and Grampian Chamber of Commerce event on this topic, he has provided his analysis on the tragic events at In Amenas and the security situation facing energy companies operating in the MENA and Sahel Regions as a topic for this month’s column.

In truth, the threat is neither new nor somehow more potent in the aftermath of the French intervention in Mali, cited by the militants and picked up by some media organisations as the reason for the attack.

Today’s militant threat has its root in the Algerian civil war that led thousands of young Islamist men to take up arms against the military establishment, following the latter’s intervention to cancel the second round of voting in the 1991 parliamentary elections.

The first round of elections had been a landslide victory for the Front Islamique du Salut (Islamic Salvation Front – FIS), the country’s then largest Islamist organisation, and the intervention was quite rightly perceived as a last ditch intervention to prevent a popularly elected Islamist government being installed.

After the imprisonment of the FIS’ older more pragmatic leaders, a young vengeful leadership sought to confront the military through violence, forming the Groupe Islamique Armé (Islamic Fighting Group – GIA), followed by the Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat (Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat – GSPC).

These armed groups used a combination of guerrilla and terrorist tactics to attack both government and security targets, as well as intermittently, civilians.

Following a series of government and military successes, which included counter terrorism operations and a government amnesty that encouraged many of the less extreme elements to re-join civilian life, the increasingly pressured and extremist GSPC leadership began to shift more towards a transnational, al-Qaeda inspired, rhetoric in order to swell its dwindling numbers.

This culminated in the rebranding of the group as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in January 2007.

For the next five years, AQIM carried out attacks on both domestic and foreign targets in Algeria, and began to extend its influence south.

It took advantage of the GIA and GSPC’s influence in the Sahel region through its southern battalions to create a safe haven.

This was facilitated by a complex network of relationships created through smuggling ties, as well as tribal and familial relationships, which form the basis of the region, predating modern colonial state boundaries.

Attacks in Algeria – although much reduced due to successful government operations – have continued at a rate of around 150 to 300 per annum over the last three years.

The group’s leadership maintains a similar appearance, with many coming from a select group of fighters that fought under the infamous Abdullah Azzam in Afghanistan in the 1980s, which provided a number of household names over recent decades.

Thus, it appears logical that the group which retains the ability to penetrate Algeria’s southern borders from neighbouring Mali, would continue to carry out attacks and kidnap operations in Algeria, targeting both government and security force targets, and foreign expatriates.

This point highlights the need for an intelligence-led approach to security on the part of foreign energy companies, in order that everyone from director level to personnel on the ground is aware of the specific threat, and the risk posed by this threat in the wider context of more common risks such as motor vehicle accident and petty and violent crime.

Only then can an efficient security regime, which is relevant to the realities of the threat and most immediate risks to personnel on the ground, be put in place.

With an understanding of what the major risks are, as well as the specifics of the threat in a regional and even site specific context, personnel are much more able to operate in a more efficient manner and play a positive role in maintaining an efficient company security policy.

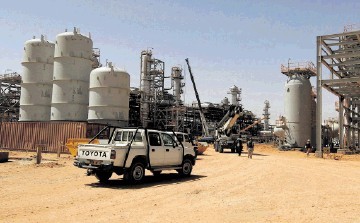

In countries such as Algeria and Libya, where physical security is solely the domain of the national security forces, a more inclusive and co-operative system involving the input of international oil companies (IOCs), the National Oil Company (NOC), which normally has a majority stake in the venture, and the national military, would also make for a much more efficient security regime, making the response to any unforeseen crises more efficient, but ultimately preventing a scenario where a viable threat is ignored or misunderstood.

Nearly two months have already passed since the In Amenas attack and the immediate flurry of reactive evacuations from the region and focus on security and the preparation of personnel has calmed.

Facing penalties for time spent not fulfilling their contractual obligations, companies have redeployed albeit amid continued concern over the safety of their personnel.

I mentioned disheartenment in the introduction and I do so as again; yet again it has taken an event that has again claimed lives to encourage a reassessment of security and duty of care requirements.

Claire Fleming is corporate relations manager at security specialist AKE