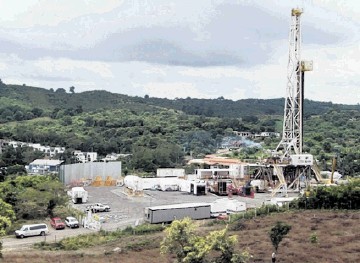

Pemex, the Mexican state oil company, has recently called for bids for those interested in exploiting the oil and gas resources of the Chicontepec region of Mexico.

The contracts on offer are the result of a controversial energy reform package approved by the Mexican Congress in 2008 in an effort to halt production decline and stimulate production.

Contracts are due to be awarded by July this year and Mexico hopes to increase the production in the Chicontepec region from a modest 70,000 barrels a day to almost 400,000bpd by 2018.

There are a number of legal structures a country can adopt when looking to use the expertise and capital of international oil companies (IOCs) and service companies to help develop its hydrocarbon resources.

Rather than offering a concession or licence, as in the UK or Norway, or a production sharing agreement (PSA) as in Indonesia or Nigeria, Mexico has chosen the service contract model.

Under this model, Pemex will remain the owner of the relevant oil fields and their production but IOCs or service companies such as Schlumberger and Petrofac (each of whom were awarded contracts in earlier rounds for other areas) will be brought in as a contractor to operate them.

In an attempt to maximise production of oil reserves, contractors will be offered costs plus a fixed fee for each barrel of oil produced but to maximise production there will also be bonuses where production exceeds output targets.

Contractors will also have to commit to certain minimum investments in development, to training of employees and to decommissioning after the 35-year term of the contracts.

Under a concession agreement or licence model, which was the earliest form of agreement used for hydrocarbon development, the licensee is granted production rights by the host state and owns all of the produced resource (but not the resource in the ground). The advantage of this to IOCs is that it allows them to book all the oil and gas reserves for financial reporting purposes.

The licensee bears all risks and funds all operations. The host state obtains its revenues in the form of royalties and taxes and may exercise some regulatory oversight over production operations but does not get involved in commercial decisions.

PSAs have become increasingly popular since their introduction in Indonesia in the 1960s, especially among developing states. In this model, the rights to the oil are typically held by the national oil company which then enters into an agreement (the PSA) with the IOC under which the IOC bears all risks and funds all operations (although the state may keep an equity stake).

The IOC is paid a share of the oil to cover its costs and the remaining profit oil is split between the state and the IOC in agreed proportions. As a result, the IOC can only book a share of the total reserves. The IOC also usually pays income taxes on income derived from the PSA.

Under PSAs, the national oil company has a direct share of production and has a say in operational decisions either through the PSA or as a partner in the IOC’s joint venture.

Under the service contract model, the state or national oil company hires a contractor which assumes all risks and costs although it is reimbursed for its costs out of production.

It is also paid for its service in accordance with a mutually agreed formula so long as commercial production targets are met, but it never owns the oil or gas produced.

It is usually paid its costs and fees in cash, although in some cases it has a right to convert the cash payment to an equivalent amount of petroleum and in these cases it may be able to book some of the reserves.

The contractor model is increasingly popular amongst developing countries as a means of maximising the potential upside for the host state and obtaining the experience of IOCs without handing over control of vital national assets.

Service contracts are therefore popular in South America where issues of resource nationalism have been to the fore; we have also advised on them in Iraq. The contractor model widens the pool of potential bidders to include the service companies, which have not tended to bid under the more traditional models.

IOCs, on the other hand, dislike service contracts because they have limited petroleum ownership rights and also limit the economic upside compared to the other models.

The process for award of these service contracts is proceeding alongside a major debate in Mexico about the future of the oil and gas sector and how to modernise Pemex’s structure and governance to allow it to reverse the recent declines in production.

President Enrique Pena Nieto, who took office in December 2012, has made overhauling Pemex a major priority under his leadership. We will be watching developments closely, with the assistance of the firm of Woodhouse Lorente Ludlow in Mexico, with whom we are developing close links.

Penelope Warne is head of energy at the international law firm CMS Cameron McKenna.

Recommended for you