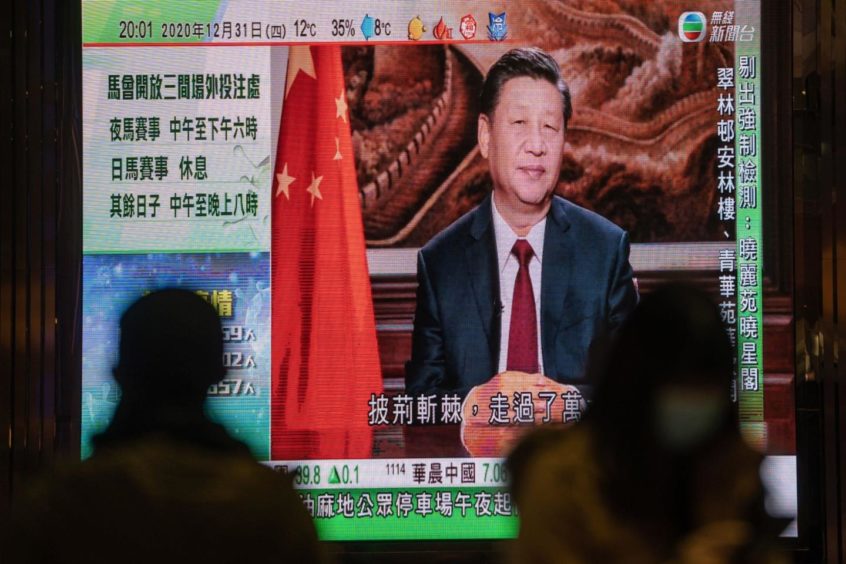

China’s newest oil refiners are thriving by aligning themselves with President Xi Jinping’s vision, expanding even as their older rivals and several other private businesses have been reined in by Beijing.

These newcomers have gained the moniker Teapot 2.0 in China, and are benefiting because they are fitting into Xi’s push for cleaner industries and greater energy efficiency.

Still little known in international trading circles, companies like Jiangsu Eastern Shenghong Co. and Hengli Petrochemical Co. are now poised to become more influential in global markets. They’ve built vast refining complexes that are more environmentally conscious and focused on using crude to make plastics and chemicals instead of more polluting fuels like diesel. As a result, some are starting to receive tax benefits or permissions to import larger amounts of crude directly from big producers like Saudi Arabia.

In June, Shenghong installed China’s biggest refining tower, and dedicated the $10.5 billion facility to the Communist Party’s centenary anniversary. Once a producer of synthetic fibers, Shenghong’s stock has rallied more than fourfold since the project began two years ago. Hengli’s stock has more than tripled since its first refinery in late 2018.

Xi’s administration has cracked down on private businesses deemed as having grown too powerful or less aligned with its vision, imposing strict controls on tutoring firms and investigating ride-hailing service Didi Global Inc. over its data practices. In the energy sector, the government is now supporting firms most closely in line with its objectives, while curtailing the more polluting first generation private refiners — called Teapot 1.0 — that have been around for decades.

“The Teapots 2.0 have a very different business and operating model which, in theory, is better suited to China’s visions for its energy sector – integrated and efficient,” said Michal Meidan, director of the China Energy Research Program at the UK-based Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

These newer firms have “a political advantage as they tick more boxes in terms of China’s future market development and priorities,” Meidan said.

China’s private refineries popped up in the early 1990s, and became known as ‘Teapots’ because of the shape of their early designs. They grew from small clay kilns that processed oil from fields like the ones in the eastern province of Shandong, which produced more than what state refiners needed.

The government clamped down on several older Shandong refiners this year by closing certain tax loopholes. The move, which coincided with more scrutiny by the government, was exacerbated by a sharp reduction in amount of crude they were allowed to import. That’s given newer firms the upper hand.

North Huajin Chemical Industries Co., one of the few listed Teapot 1.0 companies, has seen its stock fall 14% since July. The company didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Meanwhile, newer firms like Hengli and Zhejiang Petroleum and Chemical Co. still have substantial quotas to import crude, while Shenghong has applied for permissions to import for its new refinery.

Teapot 2.0 companies have built facilities at isolated islands or peninsulas, which can dock oil tankers but remain far from crowded urban areas where the Communist Party wants to cut pollution.

“This is a perfect location for a petrochemical base,” Chinese Premier Li Keqiang said during a tour of Hengli’s Dalian refinery in 2019.

The new firms may eventually face their own checks, with more scrutiny of their carbon emissions. “Potentially they may need to swap higher carbon emissions projects with lower emissions capacities if say they want to expand their capacities in the future,” said Sengyick Tee, analyst with Beijing-based consulting firm SIA Energy.

Still, many Teapot 2.0 companies have other environmental advantages because they are more advanced in aspects like waste and water management.

Hengli, which started as a chemical fiber maker in Jiangsu, began full production of the country’s first teapot 2.0 project two years ago. Its revenue has surged since then and about 66% of its 13.5 billion yuan ($2.1 billion) in annual revenue now comes from refining. State-run titans like Sinopec Group and PetroChina Co. still account for about two thirds of China’s oil refining.

The crackdown on older private refiners doesn’t mean they will all disappear, but the 2.0 firms have advantages, Meidan said. “They have economies of scale, those that are in Chinese free trade zones enjoy preferential tax treatment; they are integrated plants which gives them flexibility to shift from oil products to more petrochemicals.”

The Teapots 2.0 firms are all less focused on producing diesel and more on making paraxylene, a petrochemical used in daily necessities from bottles to sportswear, where demand has surged in tandem with China’s economic boom. That’s an area where China wants to be more self-sufficient.

Shenghong said in a statement that new techniques will helps its plant to turn more than 70% of the crude it uses into chemical products. So only a third of its crude would go into making fuels like diesel. By contrast, Sinopec Group and PetroChina Co. turn about 60% of their crude into road fuels and that ratio is at around 85% for the older private refiners.

Hengli and Zhejiang Petroleum didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Companies like Hengli in the past spent billions on buying chemicals like paraxylene overseas for their massive fiber production. But that’s changing as teapot firms produce more of the chemical at home, hitting suppliers in South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan.

In the first half of this year, China’s imports of paraxylene from South Korea, its largest supplier, was 13% lower than same period in 2019.