You do not have to look far to find arguments that the UK is more polarised than it has been for decades.

There are a whole host of issues that divide public opinion – often with rather nasty results – and more battle lines in society really aren’t needed.

Cue Siccar Point Energy and Shell’s Cambo development.

When an exploration licence for the oil field west of Shetland was approved in 2001, it is unlikely that those who signed off on it could have imagined the backlash it would have 20 years later.

Cambo, which will target around 170m barrels in its first phase, has become a battleground, one that encapsulates a wider debate about the future of the North Sea.

So far, we’ve had kayak protests, letters between leaders and rather a lot of political posturing, and that’s just been the last few months.

And with the COP26 climate conference on the horizon, it is likely that what has gone before has been merely a skirmish.

In the interest of simplicity, there are two prominent schools of thought with regards to Cambo.

On one side of the fence, there are those who want the field axed, arguing that it is at odds with the UK’s ambition to be net zero by 2050 and is a threat to the climate.

On the other is the argument that stopping Cambo would do nothing to address demand for oil and gas, it would simply cut off supply and lead to more imports.

That could also be worse for the environment as barrels could be sourced from countries with fewer commitments to cutting production emissions.

While certain politicians and environmental groups have guffawed at the idea Cambo could be climate positive, there is merit to the argument.

As advisory firm Gneiss points out, “not all barrels are equal”, some are more impactful on the environment than others and Cambo is not at the top end of that spectrum.

According to Carnegie Endowment’s Oil Climate Index, a standard barrel of light oil will generate about 475 kilograms of carbon dioxide emissions.

That covers its production, transportation and end use.

A small part of that total figure, around 35kg, will be tied to upstream operations but some other sources of oil have a significantly higher upstream contribution..

On the upstream emissions estimates for Cambo, a spokesman for Gneiss said: “Emissions intensity of 16kg CO2e/bbl, derived from the publicly available Environmental Impact Statement, appears reasonable compared to a global average of 18-19kg CO2e/boe, as estimated by Rystad Energy.”

This figures is also below the UK’s offshore emissions intensity of 20kg CO2e/boe, according to industry regulator the Oil and Gas Authority.

Moreover, it could also displace more environmentally damaging barrels imported from overseas.

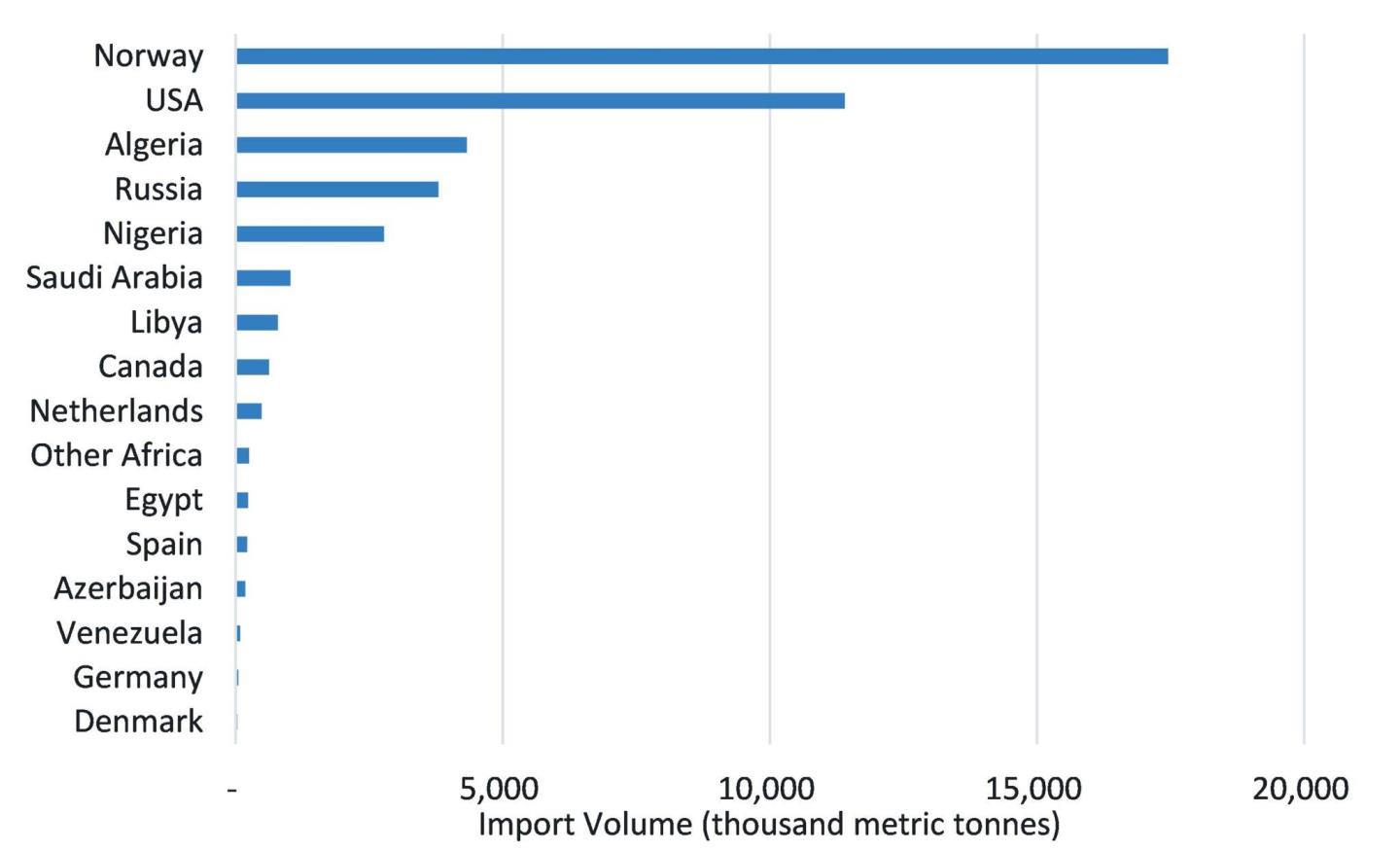

The UK has been a net importer of crude oil since 2005 and in 2018, total net crude oil imports were 3.3 million tonnes, according to the Energy Institute.

Much of the oil and gas that is imported comes from countries with a more laissez-faire approach to flaring – an emissions intensive process – such as the USA, Russia and Algeria.

According to Gneiss, Cambo will produce enough oil to offset “roughly” all of the oil imported from Algeria, the “3rd worst offender globally for flaring intensity”.

ENGINEERED SCENARIOS

A spokesman for the organisation said: “It is far easier to measure, and create incentives to improve, domestic upstream emissions than to influence the operations of the global crude market.

“However, post-Brexit the UK does have some flexibility in its trade policy and there are options that could be considered to prioritise imports from countries with less flaring.

“These range from diplomatic moves to request that countries that supply oil to the UK endorse the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 Initiative, as the UK has done, to enforcing sanctions or penalties on imports from countries where flaring is deemed to be unacceptably high.”

He added: “Cambo won’t have the lowest emission profile on the UK Continental Shelf but it will be better than the current UK average and will therefore take that average in the right direction – increased imports may do the opposite.”

But, a scenario by which Cambo directly replaces imports from high flaring countries is “engineered” and “unrealistic”, Gneiss said.

Instead, it is likely that some of barrels produced from the west of Shetland field would come at the cost of those from Norway, the UK’s biggest source of imports and a leader in low upstream emissions.

As such, any displacement of barrels from across the North Sea could actually “worsen the UK’s carbon footprint”.

To try and ensure that barrels for the worst flaring offenders face the chop, the UK could look to roll out “carbon border pricing”.

But Gneiss warned that “challenges in assessing the carbon emissions profile of any given cargo” would likely be an “impediment to implementing this unilaterally”.

As “no amount of modelling” would be able to accurately predict the environmental impact of Cambo, Gneiss said the only way to ensure it is “net positive” is to strive to be best-in-class for carbon intensity.

As scrutiny of the industry intensifies, all future North Sea developments, such as BP’s Clair South and Equinor’s Rosebank, are looking to keep their operational emissions to a minimum.

Cambo is no different and is being built “electrification-ready”, meaning its assets could be powered using renewables.

But, Gneiss says the plans to keep emissions low could have gone further.

“First concrete was poured at the 433 megawatt Viking wind farm on Shetland recently and yet there are no current firm plans to use this clean shore power at any fields in the area. This is just one example of missed opportunities to reduce upstream emissions.”

Indeed, there is also scope for Rosebank and Clair South to tap into Viking, an idea that is currently being explored by the ORION project in Shetland.

Equinor is also considering using a floating wind farm to power Rosebank, building on its Hywind Tampen development in Norway that will supply energy to the Snorre and Gulfaks installations.

Initiatives such as these will help to build up the scientific case for future North Sea production, as ultimately this is what the debate around Cambo truly boils down to.

Gneiss said: “A political block on development of Cambo would undoubtedly set a precedent for other development projects on the UK Continental Shelf.

“The particular public relations dynamics surrounding COP26 may not apply to discussions about future developments, however, that is unlikely to diminish the pressure to take a consistent approach.

“Even without an explicit shift in policy, the cost of capital for pursuing UK developments would become dramatically higher.

“Projects with specific features, such as gas resource rather than oil and those able to extend the life of existing infrastructure, may be more likely to be able to continue unaffected.

“However, the appetite to pursue even these would be substantially reduced by the new regulatory uncertainties that would have been introduced.”

© Gneiss Energy/ BEIS/ DUKES

© Gneiss Energy/ BEIS/ DUKES