Transparency is a bit of a buzzword within the oil, gas and mining sectors currently following developments at both UK and EU level.

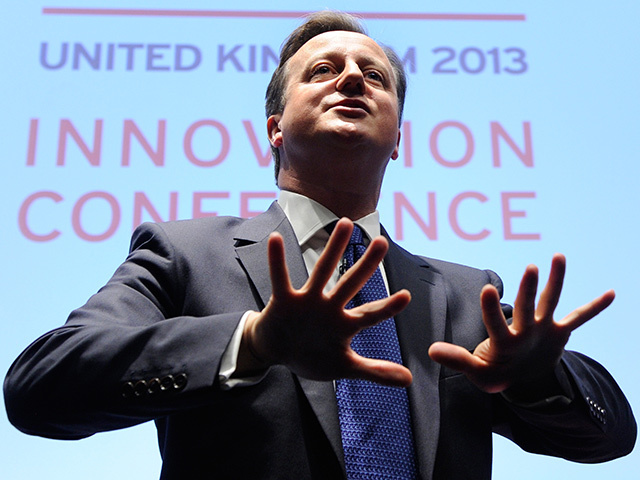

In May, our PM, David Cameron, announced that the UK (alongside France) will be implementing the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

Last month, the European Parliament approved amendments to the Accounting and Transparency Directives (the Directives) to require companies within the extractive industries to disclose details of government payments made in relation to projects in which they are involved.

EITI describes itself as “a global standard that promotes revenue transparency and accountability in the extractive sector. It has a robust yet flexible methodology for monitoring and reconciling company payments and government revenues from oil, gas and mining at the country level”.

The initiative was developed by a coalition of governments, investors, companies and international organisations. The ethos behind EITI is that transparency is the most successful means of combating corruption.

If citizens know how much money their government is receiving from extractive projects in their country they are better able to hold their government to account for how that money has been spent.

EITI is not a programme which governments can adopt simply by signing up but instead sets out principles to be adopted in a manner tailored to each country’s requirements.

A country signing up must demonstrate its commitment to implementing EITI by developing objectives and a plan to reach compliant status.

To be compliant, EITI requirements (of which there are currently seven) must be met. These include the creation of a multi-stakeholder group to oversee the implementation of the initiative, and timely publication of EITI reports that provide full disclosure of extractive industry revenues and disclosure of all material payments to government by oil, gas and mining companies.

Such reports must be subject to a credible assurance process to international standards, must provide data in a comprehensible and publicly accessible way and any lessons learned must be acted upon.

The support for greater transparency within the extractive industry is illustrated by the fact that around 40 countries have already signed up to EITI and between 2009 and 2013 the number of compliant countries increased from only two to 21.

In addition, EITI has also gained the support of both a large number of companies within the oil, gas and mining sectors and global investment organisations. The recent commitment of the UK and France suggests that, as EITI says, “transparency management of the extractive industries is not an aspiration for countries, it is an expectation”.

Of course, there are two ways of ensuring that income is reported – it can be disclosed by the recipient government or the paying company – the EU is tackling the problem from the latter perspective.

The amendments to be made to the Directives will create mandatory reporting obligations for companies in both the extractive and forestry sectors.

Under the new rules both EU listed companies and large non-listed EU companies are required to disclose any payments over the value of 100,000 euros (including for example taxes and licence fees) made to any government, and not just EU governments.

The rules apply on both a country-by-country and project-by-project basis. In order to be deemed a large non-listed EU company, such company must meet two of the following conditions. It must have: assets of more than 20million euros, turnover of more than 40million euros or an average number of employees equal to or greater than 250.

The Directives are intended to hold governments accountable for their use of revenue, and not to make business more difficult.

However, the obligations they place on companies may give rise to problems in practice.

In particular, certain countries may prohibit the disclosure of such payments.

This could put companies in the difficult position of potentially having to withdraw from a project if they cannot obtain consent to disclose the information required.

Requests were made for the inclusion of an exception to address this problem.

However, it was felt that while such laws appear to be rare at present, allowing such an exception would simply encourage countries to pass such laws in order to escape disclosure.

Other concerns include the costs of implementing new measures to ensure compliance and commercial consequences associated with disclosing sensitive information.

The amendment of the EU Directives and the UK’s commitment to EITI indicate increasing momentum for improved transparency in the extractive industries worldwide.

Although the developments may not in themselves be a complete solution, they have the potential to provide benefits for both countries rich in natural resources and companies in the sector in tackling the “resource curse”.

Implementation provides a clear signal to investors and institutions like the World Bank that a government is committed to greater transparency and so can lead to increased overseas investment.

By strengthening accountability and good governance, the initiative can promote greater economic and political stability. This, in turn, can contribute to the prevention of conflict.

Such long-term stability is in itself a good thing for companies making investments in the extractive industries, which are capital intensive and will take a long time to generate returns.

Transparency also assists in creating a level playing field between companies and has reputational benefits in allowing companies to demonstrate the contribution that their project makes to the host country.

There are still some problems which may be encountered along the way but if the international commitment to transparency continues to grow, these problems may be resolved over time leading to a rosier future for resource rich countries.

Penelope Warne is head of energy at international law firm CMS Cameron McKenna

Recommended for you