The North Sea industry not many weeks ago marked the Piper Alpha anniversary and debated how best to ensure that disasters like this can never happen again.

In a few weeks, some at least will mark the close call that the North Sea drilling rig Ocean Odyssey had on September 22, 2008, when it suffered a blow-out (see p33).

And of course, the US Gulf of Mexico post-Macondo legal juggernaut continues to greedily growl along, getting fat off $billions of claims against BP and others for the disaster of April 2010 that led to the loss of the rig Deepwater Horizon.

All three will figure somewhere in the 2013 Offshore Europe conference and exhibition, which has attracted tens of thousands of delegates to Aberdeen.

The three incidents, coupled with the sheer scale of the industry as evidenced by the success of OE for 40 years thus far, demonstrate how many people are employed by the offshore industry, not least in the Granite City, and can be affected by an offshore incident of any scale.

Indeed, various recent situations both on- and offshore have forced companies to examine how incidents impact not just those employees directly affected but also the families at home and the wider workforce.

This requires specialist input, which is why companies such as Altor Risk Group, set up in 2010, are today a part of the safety, emergency response and legacy issues jigsaw.

The firm has a programme known as “Care for People”, which is based around supporting the individual during and after an incident.

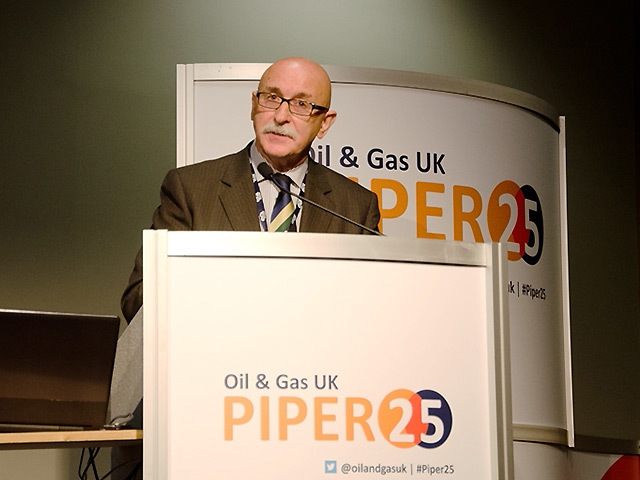

“We strongly believe that it is vital for companies to work with everyone affected in an emergency situation,” says Albert Thomson who leads the programme for Altor.

“It’s not just casualties companies need to focus on. The wider workforce, first responders, medical staff and, of course, the families of those directly affected need just as much consideration.”

Thomson has logged 30 years of experience as a police officer in Aberdeen during which time he worked in the Force Control Room. Here he provided police response to the Ocean Odyssey blowout and the Chinook and Cormorant Alpha helicopter crashes. After leaving the force, he began advising a variety of organisations across the world on disaster management, with a particular interest in relative response work.

“Caring for People extends the planning process that organisations already have in place should the worst case scenario occur,” says Thomson. “Our role is to help them develop that approach with a particular focus on delivering bad news to families.”

The programme covers a traditional relative response function as well as family liaison work and dealing with the resulting medical and psychosocial matters.

While it complements a traditional HR function, Thomson warns that it runs deeper. “This affects all departments and in the case of an emergency, it will call upon more resources than HR can provide. Organisations should ensure that their response is joined up, visible and fit for purpose. It must be organic.

He points out that rapid advances in technology, notably social media must be taken into account. News gets out faster than ever before and through the most unexpected channels.

Thomson claims Altor has a grip on this issue and that the group works with clients “to ensure they have robust methods in place to reach the next of kin before external sources approach them”.

Thomson is clear that risk will never disappear; similarly, when there is a loss of life, the pain cannot be diminished.

“I feel that it is vital for companies to adopt the same principle that we see in medical ethics – ‘first, do no harm’. What we must strive for is that everything is done to ensure that a difficult situation is not made worse,” he adds.

Recommended for you