As Offshore Europe gets ready to celebrate its 50th anniversary event, we launch our monthly series looking at each decade of the showcase.

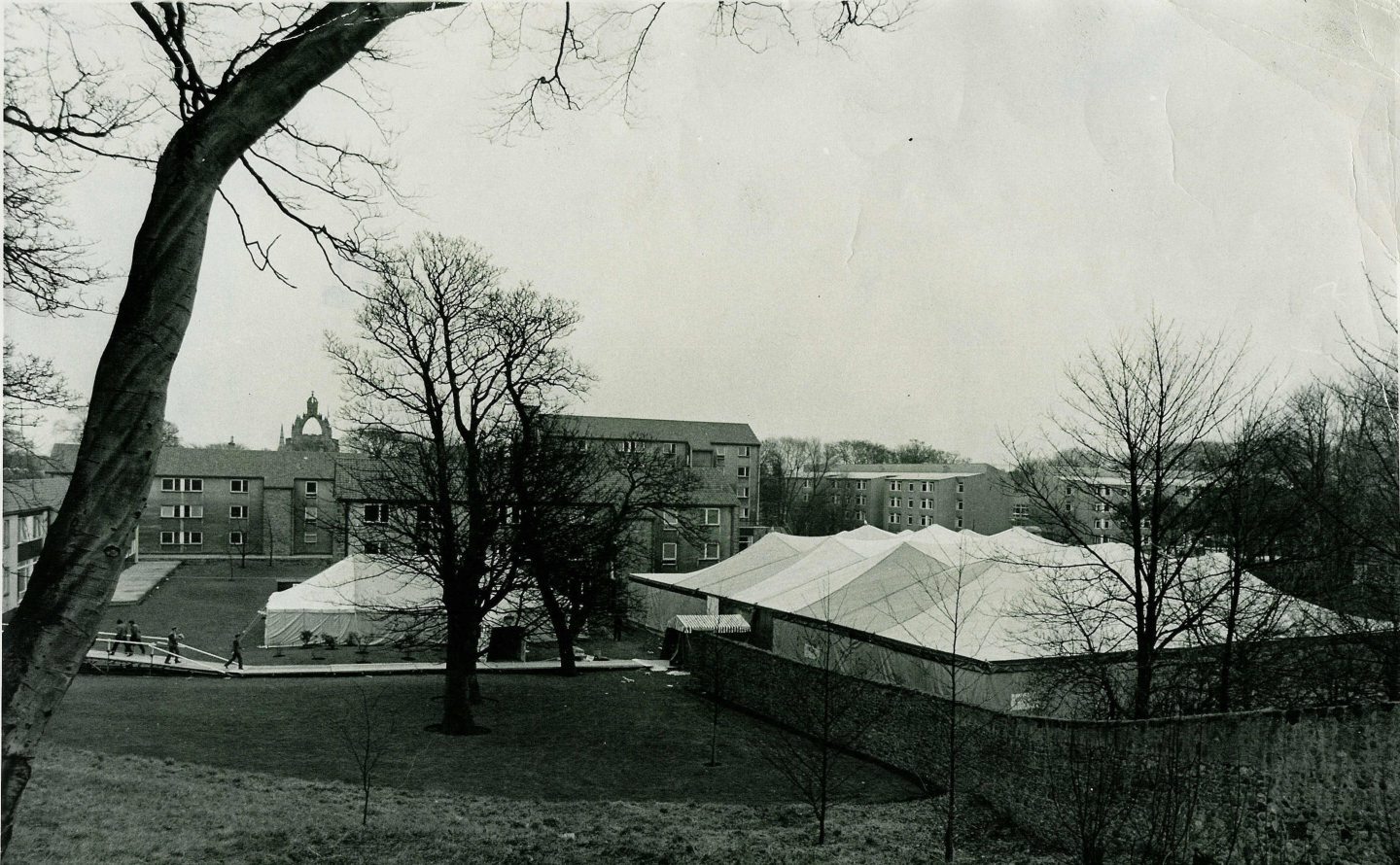

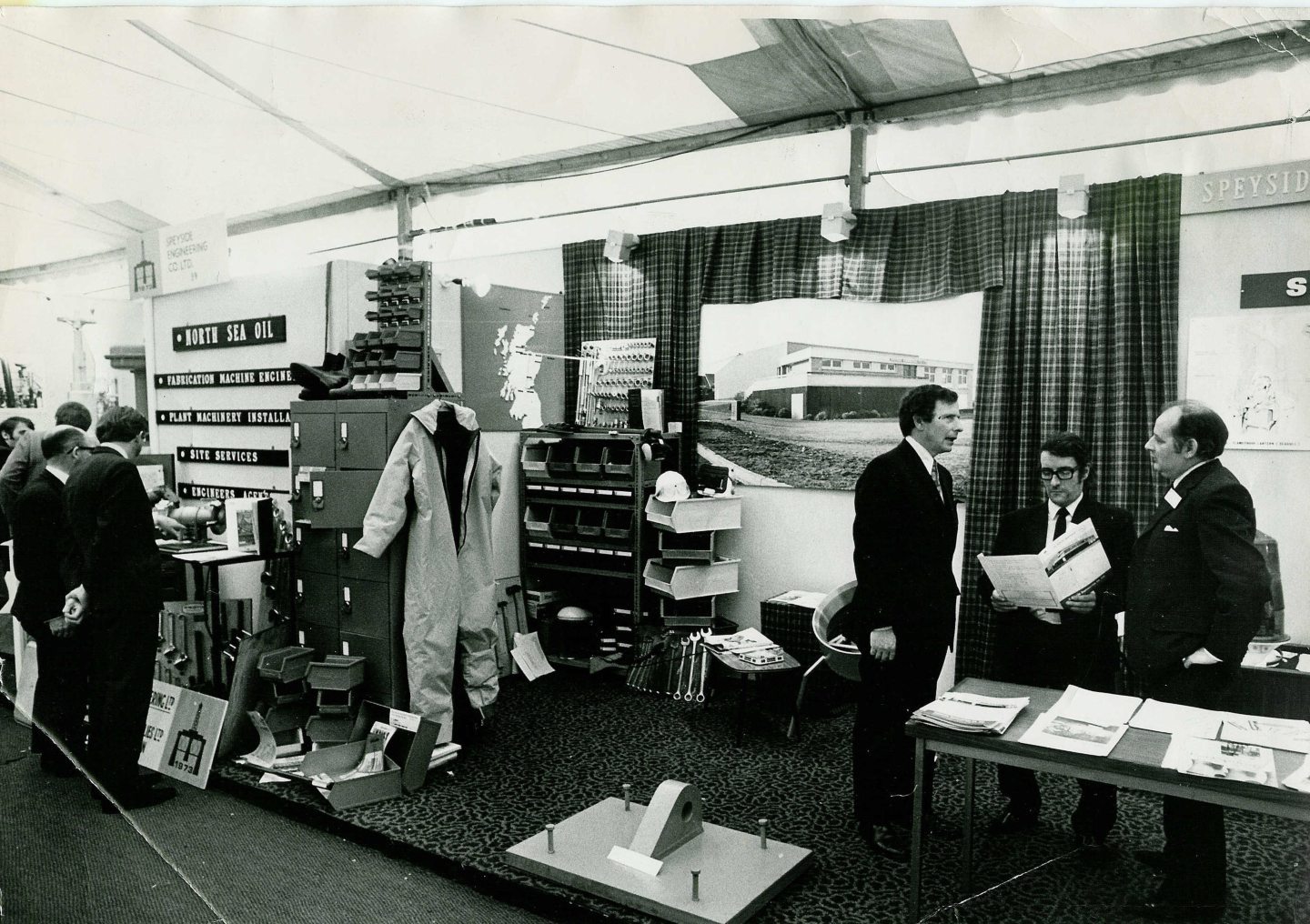

Offshore Europe was first staged in March 1973 in the grounds of Aberdeen University and Aberdeen Arts Centre against a background of massive energy promise and virtually a decade after the first UK Oil & Gas Licensing Round had been launched.

Today, some 60 years after the UK offshore industries fiscal foundations were laid, it is hard to imagine what the start of the North Sea hunt was like in the 1960s.

It’s a tale of poorly equipped companies battling against the elements in their quest for riches, encouraged early on by a six exciting gas discoveries made in the Southern North Sea, starting with BP’s West Sole find of December, 1965.

But, while gas was easily found, oil proved elusive. No fewer than 22 gas finds were to be made in the UK North Sea before Amoco located the small Arbroath oilfield in 1969.

And five more finds were made before BP hit the jackpot with multi-billion barrels at Forties and sparked the klondike that was to transform Aberdeen into the Oil Capital of Europe and revitalise UK government finances.

Forties was discovered 110 miles east of Aberdeen in November 1970, with production starting in September 1975. Shell made its massive East Shetland Basin Brent oil find in ’71, didn’t go public until September 1972 and fast-tracked it to first commercial production by 1976.

Until Forties and Brent, the Southern North Sea fishing town of Great Yarmouth had been the focal point of early activity, with the tally of gas finds rising rapidly and fields being put into production as fast as possible.

Helping to fuel early gas buzz excitement were various pioneering conferences and exhibitions and quartering the quaysides of Yarmouth at that time was David Stott, who already knew the place and Aberdeen too as he had been a fisheries journalist in his early working life and was wondering how to cash in on the putative North Sea boom.

Reminiscing with the writer about Offshore Europe’s beginnings, David said: “It all began as an idea hatched in a holiday camp in Great Yarmouth.

“It was Spring 1971, and the occasion was an exhibition – Oceanex – with which my tiny publishing company, Spearhead, had become involved.

“But, as a result of the dramatic announcements about oil finds in the Northern North Sea, it seemed to me that Aberdeen would become the main centre for offshore activity in the future.

“I had knowledge of the city and some very limited experience of exhibition organising.

“After some research and with a great deal of trepidation, I gave a small press conference at the Station Hotel in April 1972, announcing the go-ahead for an oil and gas event in Aberdeen.

“But we would never have got Offshore Scotland (as it then was) launched if it was not for four men – John Hutton and Jim Dinnes of the North-East Scotland Development Authority (NESDA), and Alan Robertson and Jim Main of the University of Aberdeen.

“Because of their invaluable advice and help, we were able to plan for the first show (based on tents) to take place in 1973 in the Chemistry Car Park of the University, with the conference in the Arts Centre.”

March 20-23 was selected despite a Dutch contact warning David that staging a tented show in Aberdeen so early in the year was mad beyond belief. But he persisted.

“As it was, we managed to attract 140 exhibitors, who became too hot in a temperature of over 70oF as the sky was blue and the sun blazed down on the canvas roof.”

Offshore Scotland was hailed a great success despite a few hoax bomb calls. The day after the show closed, snow fell and the East wind struck chill!

David had got away with it! Time to get planning for the next Aberdeen show. And a crucial catalyst became the short-lived Yom Kippur War of October 1973 when the Egyptian military rolled into Israel.

OPEC reacted by limiting oil supplies as a deterrent to Western powers stepping into the fray.

Because of Yom Kippur, in just 12 weeks the price of crude rocketed more than 400% … delivering perfect conditions to accelerate the North Sea oil and gas hunt beyond everyone’s wildest dreams at the time.

“We knew we had the potential for a much larger event, and once again NESDA came to the rescue by suggesting the Bridge of Don showground, owned by the Grampian Regional Council (GRC),” said David.

The show was rebranded Offshore Europe, moved to a September date in 1975 and, as the North Sea finds and developments came thick and fast the orders poured in.

However, the danger of being overwhelmed by success became very real, not least because the “infrastructure was entirely inadequate”.

“In our naive optimism we underestimated the difficulties,” admitted David.

“We erected a vast tented village – nicknamed ‘Tentie Toon’ locally – to house some 800 exhibiting companies from all over the world, and awaited an onrush of visitors.”

On September 16, the opening day of the show, Aberdeen became a gridlocked city. Nothing moved on the roads, as the oil world and some rubberneckers – 36,000 in total over the week – poured in from all points, headed for Tentie Toon.

David: “The exhibition wasn’t ready – the aisles full of rubbish. When I accompanied Willie Ross, then Secretary of State for Scotland, down South Anderson Drive in his official car on the wrong side of the road, following a police escort, frustrated drivers shook their fists at us as we passed.

“The show staggered from crisis to crisis, culminating in a torrential all-night downpour that nearly took the roof off some of the tents, and making such car parks as we had uninhabitable, so that we had to introduce a fleet of emergency buses from the Esplanade to get anyone to the show.

“Somehow, the exhibitors did a lot of business. We had survived despite a withering public dressing down from Sandy Mutch, then Convener of Grampian Regional Council, which I remember to this day.”

But this was a case of the ill-prepared absolutely having to go on. The North Sea was going like a train, Aberdeen really had become a goldrush town.

Lessons were learned from that first Offshore Europe, various key and enduring appointments were made and cash invested in the show.

“We invested £120,000 of our own money in the site – It seemed a fortune at the time – laying down a hardy Bitmac surface covering much acreage to include proper car parking as well as exhibition space.

“And we rented a brand new and greatly superior type of temporary structure from Aberglen (an Aberdeen company owned by local entrepreneur Jimmy Milne).”

As a result and bolstered by masses of oil coming ashore from Brent and Forties, the 1977 and 1979 shows were a success. But it also became obvious to David that as a major international event the infrastructure of OE left a lot to be desired.

“We had already attracted serious competition when the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE), organisers of the OTC in Houston, and in co-operation with the Montgomery Group, launched a major rival in 1978 in Earl’s Court, London, repeating in 1980.

“The new Scottish Exhibition Centre (SEC) in Glasgow was in the final planning stages, and there was a political desire either to attract OE to Glasgow, or to set up a new oil show in the modern halls, with full conference facilities and all the trimmings.

“I suspect that behind the scenes we had some discreet and heavyweight backing from then minister of state for energy, Alick Buchanan-Smith, and (the legendary) John d’Ancona, director-general of the UK government’s OSO (Offshore Supplies Office).

“GRC made several valiant but unavailing attempts to fund a centre at the Bridge of Don; not however consulting us in the process.

“We were looking decidedly shaky without major improvements, so, under fire from all sides, we swallowed hard and set about trying to raise the finance to build a centre ourselves.

“We appointed architects, drew up a plan and after a lot of pressure we finally met our target, the investment being provided by the Royal Bank, GRC , ourselves and – grudgingly – from the Scottish Development Agency, which was of course a firm backer of the SEC.”

AECC was completed just in time for the 1985 show.

“At last, we could hold our head up high and know that we could compete with anybody.”

Offshore Europe was two years into its second decade.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by AJL

© Supplied by AJL © Supplied by -

© Supplied by - © Supplied by AJL

© Supplied by AJL