Distorted price signals and poor messaging around Zambia’s move towards solar has obscured the challenges of new renewable generation in sub-Saharan Africa.

A new paper from Energy for Growth’s Teal Emergy examined the Scaling Solar Program, by the International Finance Corp. (IFC).

A solar auction in Zambia in 2016 set records with tariffs as low as $0.06 per kWh. This Scaling Solar plan, though, “did not scale”, Emery wrote in a new paper. The broader plan also failed to provide a widely replicated model.

The IFC targeted 1 GW under the Scaling Solar plan by 2019. There are now only three projects under the plan, with about 245 MW of capacity.

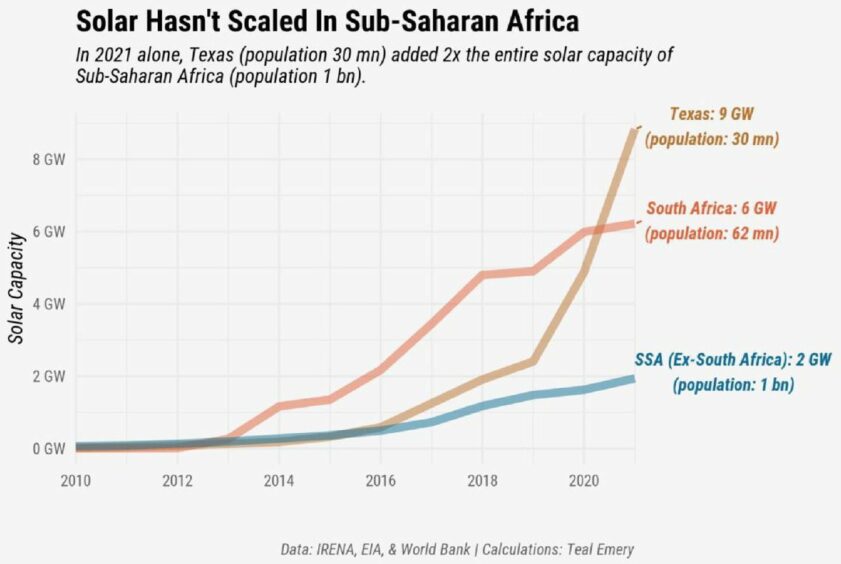

Sub-Saharan Africa “remains a laggard” in solar power access.

Scaling Solar was well designed, wrote the analyst. “However, official messaging undermined the program’s goals by denying or downplaying the critical role of explicit and implicit subsidies in Zambia’s success,” he wrote.

Distorted price signals hindered the efforts of African governments and solar developers.

The initiative also “undercut the case for the expansion of concessional lending”, which would have reduced the cost of capital.

The IFC should acknowledge that concessional lending will continue to play a major role in the sector, Emery concluded. Furthermore, there must be more clarity on explicit and implicit subsidies, with transparency on power contracts.

This latter point would help “market participants to scrutinize pricing drivers and prevent the accumulation of large undisclosed public debts”.

Magical solar story

Emery said that senior leaders at the IFC had undermined the “ambitious and thoughtfully designed” plan through a desire to “tell a magical story where a pinch of best practices and a dash of de-risking” would be enough to unlock the required financing.

The project in Zambia was achieved through “cheap [development finance institution] DFI was a primary driver” of the record low tariff. Private investors have imposed high prices on capital not because of their unfamiliarity with deal structure, Emery said, but because of “genuine credit risk”.

No country has carried out a second round of Scaling Solar projects, the analyst wrote. Zambia’s success appears to have been by substantial DFI funding, although the details are “shrouded in opacity”. The project was simply unviable using market interest rates, he said.

The World Bank said at the time that the African solar project had no “implicit or explicit subsidies”.

In addition to the unclear DFI funding, companies renegotiated deals after closing, Emery said. Quoting a USAID report, he noted IFC did not disclose these renegotiations seemingly out of embarrassment.

As a result of not coming clean, other governments in Africa cancelled various solar projects. Furthermore, the message that concessional financing was not needed put off other DFIs from backing other solar projects.

The true cost of securing $24.5 million from solar developers in Zambia was $81mn of cheap DFI debt and a $5.7mn payment guarantee. With higher borrowing costs now, DFIs should disclose all subsidies, Emery said, so that participants can see “clear price signals”.