Roughly one third of the oil and gas workforce now comes from Generation Z and it’s the same for most other industries.

One of the biggest issues this simple fact raises for bosses in petroleum companies and across the industry’s supply chain, not least whether enough is being done attract and retain this tech-savvy and environmentally aware cohort.

Born between 1996 and 2010 and according to a Society of Petroleum Engineers publication, GenZ “represents one of the clearest signals that the great crew change has come and gone”.

And yet big questions remain about whether oil and gas companies have fully adapted to this reality, and various SPE papers presented over the past few years suggest that they have not.

Take safety and how it relates to management the situation is stark, possibly dangerously so.

There is attention paid to safety within the various tiers of management and bandying about of statistics but how much of this is tokenism. In the context of the Piper Alpha, corporate memory of this horrible disaster 35 years ago has effectively vanished.

The closest today’s industry can reach out to extant corporate memory is the loss of the super rig Deepwater Horizon in the US Gulf of Mexico on April 20 2010 when eleven offshore personnel perished and 17 were injured.

However, one suspects that even that is now tenuous, partially at least because of fundamental differences between North Sea and GoM cultures and the mobility of their respective workforces.

But there is something else. There are now five generations in the workplace; though perhaps rare in oil and gas. Nonetheless, there are five: GenZ right through to people still working in their 70s. Each generation spans about 10 years.

The generational gap in the workplace is, broadly speaking, the difference in behaviour and outlook between groups of people who were born at distinctly different times.

Each generation grows up in a different context and, as a result, may have different work expectations.

For instance, members of the silent generation are typically depicted as being very fiscally conservative, while baby boomers may show more liberal fiscal tendencies.

Safety Summit

GenZedders are heavily tech-reliant and comfortable using social media platforms, while older generations may prefer other forms of communication. And they may approach safety differently too.

Which is precisely why, at this year’s upcoming CHC Safety & Quality Summit on November 14-16 in Canada, a new format will be introduced.

Arguably the most innovative change will take place the day before the conference itself, November 12.

“On Monday we will be running a full day of ‘next generation’ training for high potential candidates who we hope will lead our industry in the years to come,” say the organisers.

“These next gen delegates will join us at the conference from Tuesday onwards as we explore and develop new safety mindsets. Together, we will develop a succession plan to ensure the safety and quality of our industry in 2024 and beyond.

“Much has changed in the past five years. The offshore helicopter industry has had to adapt – quickly – to meet changing demands.

“As the pace of change has accelerated, it has sparked a state of permacrisis with little time to regroup. Simultaneously, the accident rate has accelerated, from an all-time low in 2019/20, to 12 fatal accidents and 18 lives lost in 2022.

“Were we distracted, complacent, without the focus and resources? How do we enhance safety, succession and sustainability in a dynamic industry?”

The theme this year is ‘Reset 2024: Developing New Safety Mindsets’.

This echoes the post Piper Alpha disaster period when safety soul searching and vowing to do better was top of the North Sea agenda.

But it took a disaster to make this happen. Similarly the reset theme at the 2023 CHC summit.

It is also important to recognise that the event is led by CHC, which has a sizeable North Sea presence.

Corporate memory in oil and gas safety and the next gen

Perhaps Big Oil will be able to learn from the summit, in particular the ‘next generation’ training day, and apply it in the North Sea when endeavouring to drive home the criticality of safe working practices and effective response to a crisis.

At the very least its leadership needs to be in a position where it is managing safety with equal competence and that includes the make-up of the workforces of every company involved. That composition is changing profoundly too.

This latter point was driven home starkly at a seminar hosted last year by GDS, a corporate performance analyst based in Bristol.

Everyone in the North Sea surely knows that, from AI (artificial intelligence) to the cloud to robotics and analytics, emerging technologies are transforming the world of oil and gas.

Digital tools are optimising processes, reducing costs and lowering risks.

But the next-generation oilfield requires a next-generation workforce while tapping into the knowledge of seasoned workers and, willy-nilly, that is supposed to include on the safety front.

At GDS’s most recent oil and gas summit, a gathering of execs responsible for driving digital change made various workforce predictions and examined what the future of work in the industry will look like.

Rosemary Freeman, senior manager of global exploration and production planning at Hess in Houston predicted: “Soon, there will be more data scientists than engineers in oil and gas, that’s where technology is taking us.

“In order to keep up with this digital revolution, the C-suite – bosses – needs to make digital a priority, drive a culture of change and invest in people with great talent.”

Freeman is putting the onus on the C-suite saying, “A lot of what we are predicting in here is not really common knowledge among employees in oil and gas; there is just a subset of people who know how technology is moving and how it will impact oil and gas. They are aware of it in their personal lives but not how fast it could change oil and gas.

Automation and AI

It is well known that automation is displacing jobs in oil and gas though it is strangely late into the North Sea.

However, some in the industry believe machines will never do it all on their own.

Jim Claunch, VP of business efficiency at Equinor said at the GDS session: “I think the future of work in oil and gas is a relationship between man and machine. I don’t believe machines will be an independent entity, accountable on its own.

“We’re going to need translators, people that can speak sub-surface and those who can speak machines and look at code and be able to bridge the two together.”

“We need more leaders that truly get digital but also really get the transformation and what’s possible and I think what we’ll see is those companies that have executives that can do that will be successful.”

It has long been recognised that removing the human being from offshore can deliver a worthwhile safety dividend, even if it turns out to be a collateral benefit to the core cost savings objective and arrived at more by accident than design.

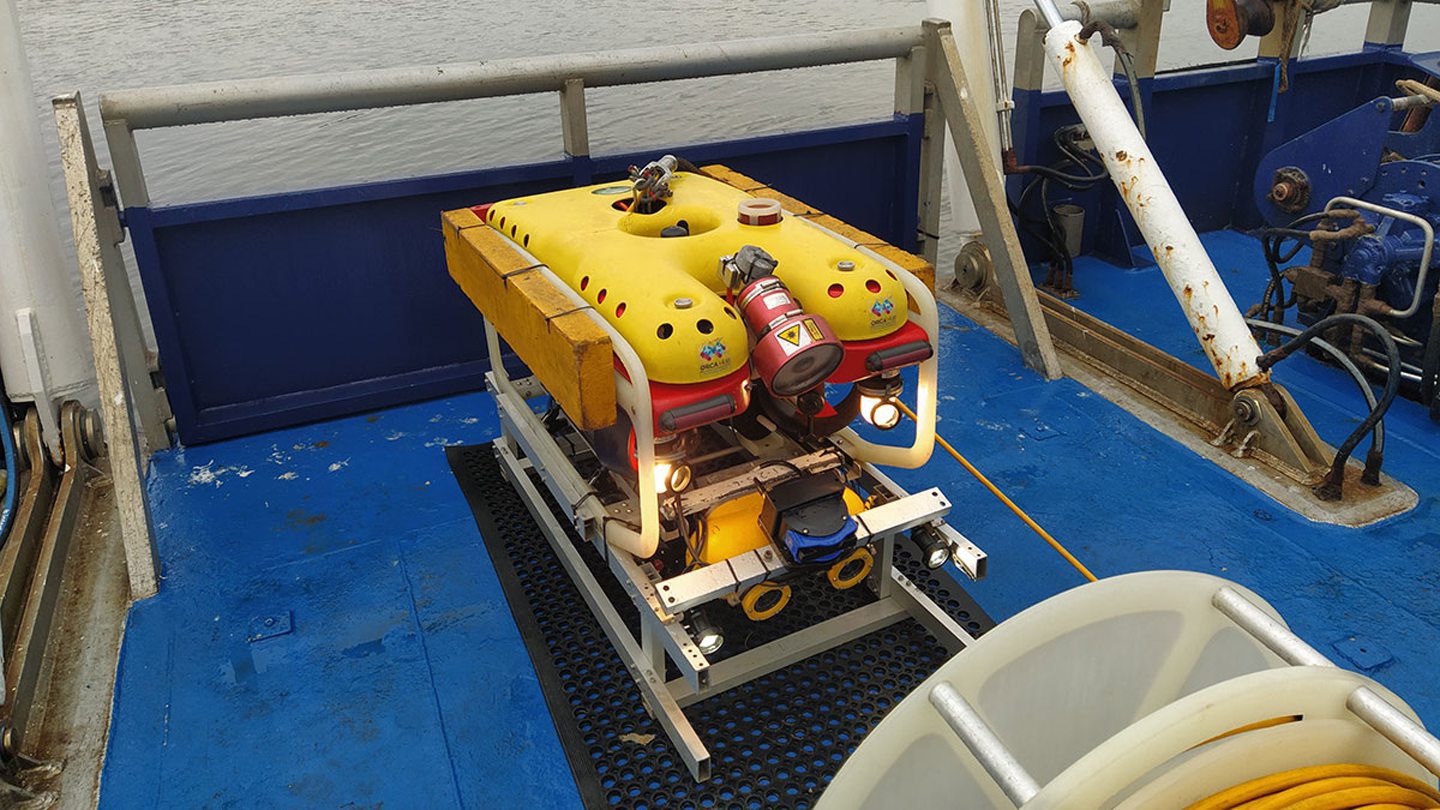

A fine example of how AI can potentially protect lives and prevent offshore disasters is research at Scotland’s Heriot Watt University at the ORCA offshore robotics hub, which is a five-universities initiative.

They have combined artificial intelligence (AI) with a specially developed radar technology to create a state-of-the-art digital architecture known as Integrated Edge-Robotics Information eXchange (IERIX).

The software can operate autonomously to carry out detailed assessments including the condition and performance of offshore installations, including wind turbines and can also be used to simulate offshore emergency scenarios and forecast outcomes to inform on vital incident planning.

Regardless of such solutions, resolutions made by corporations following a major disaster, and diktats made by regulators, managers cannot duck their responsibilities regarding safety.

But how does the oil and gas or indeed any other industry with their GenZs and C-suites get around the issue of how long the impacts of an incident may last within a company.

Well, according to research conducted for the American Institute Chemical Engineers (UK equivalent is IChemE), which has a considerable profile in upstream and downstream oil and gas, it’s very fragile indeed.

In a nutshell it boils down to this:

· After three years , memories of the incident were almost completely gone;

· The few people who remembered an incident were either directly involved in the incident, or were responsible implementing corrective actions following the incident;

· To those not involved in the incident or corrective action, it was as if the incident had never happened.

Sobering or what?

Recommended for you

© Supplied by AP

© Supplied by AP © Supplied by ORCA Hub

© Supplied by ORCA Hub