Policymaker targets for global offshore wind are “unrealistic” due to the tens of billions of dollars of investment needed near-term in the supply chain.

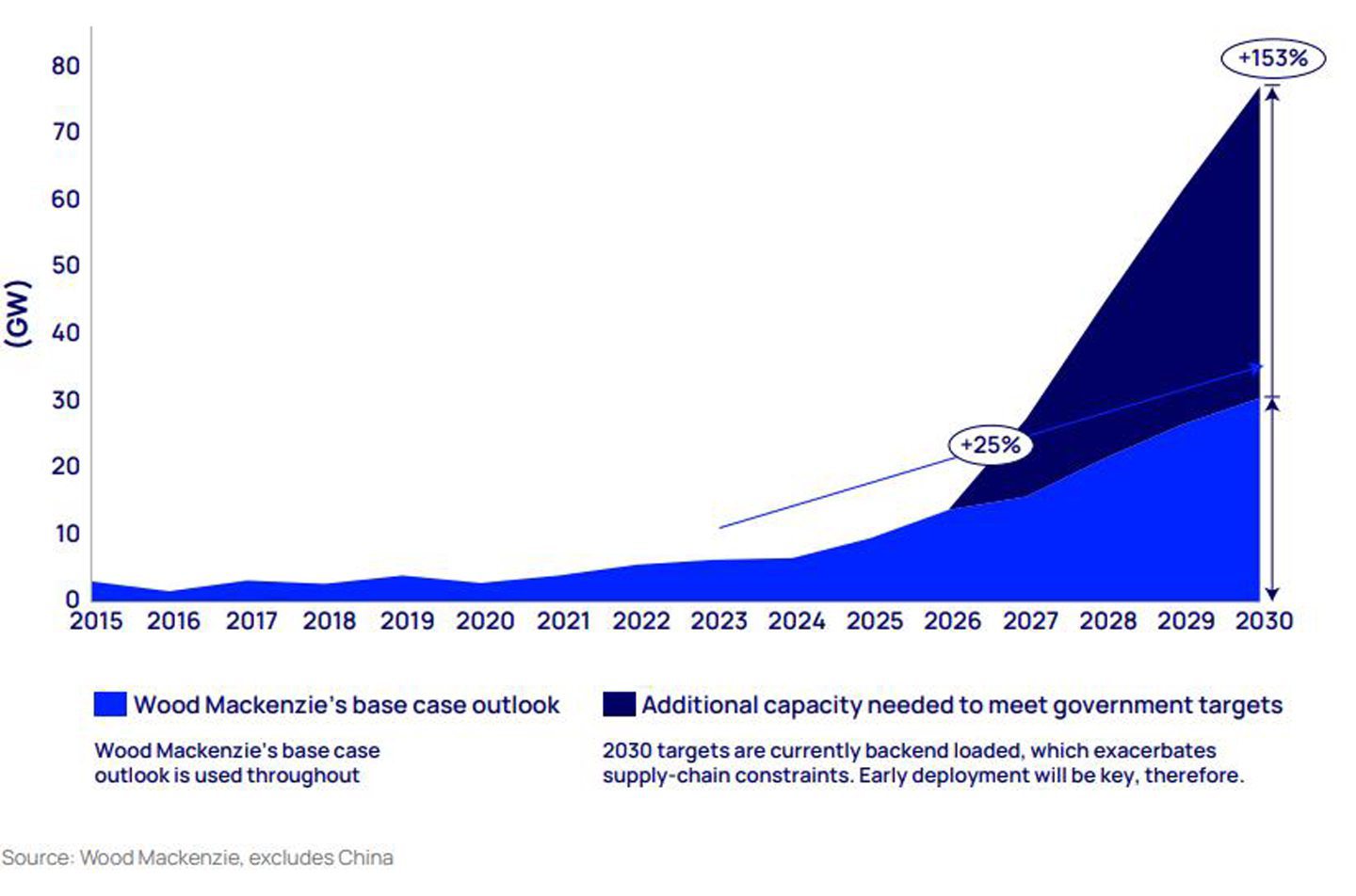

Analysis from Wood Mackenzie has set out the investment needed to hit the “base case” of adding 30GW annually by 2030, and the much larger policymakers’ targets of 80GW.

To hit 30GW of additions, some $27bn of investment needs to be secured by 2026, the analyst firm said, which rises to $100bn in order to hit governments’ 80GW target.

It comes as offshore wind suppliers are struggling with inflation pressures, and an oversupply in 2015 which has seen firms become more cautious to invest.

‘Unrealistic’ offshore wind targets for supply chain

Chris Seiple, vice chair of power and renewables at Wood Mackenzie, said: “Governments have made clear their commitment to offshore wind as an important pillar of decarbonisation and energy security. However, the supply chain is struggling to scale up and will be an impediment to achieving decarbonisation targets if change does not happen.

“Nearly 80 GW of annual installations to meet all government targets is not realistic, even achieving our forecasted 30 GW in additions will prove unrealistic if there isn’t immediate investment in the supply chain. Adjustments and new policies by governments and developers will be required to transform the supply chain to deliver offshore wind projects at industrial scale.”

Developers, manufacturers and marine contractors have all felt pressure over commodity costs and inflation, with some turbine manufacturers reporting billions in losses.

Mr Seiple added: “The oversupply that resulted from the 2015 supply chain buildout is one of the factors depressing profitability, which saw the industry boost its capacity to supply around 800 turbines, compared to the yearly average of 500 since then. Suppliers are now also having to cope with the inflation of the past two years and higher commodity input costs.

“Burned once, current suppliers are cautious in their investment plans and the lack of profitability is hampering their ability to fund manufacturing capacity expansion – ultimately stalling innovation in the sector.”

Scale up or fall behind

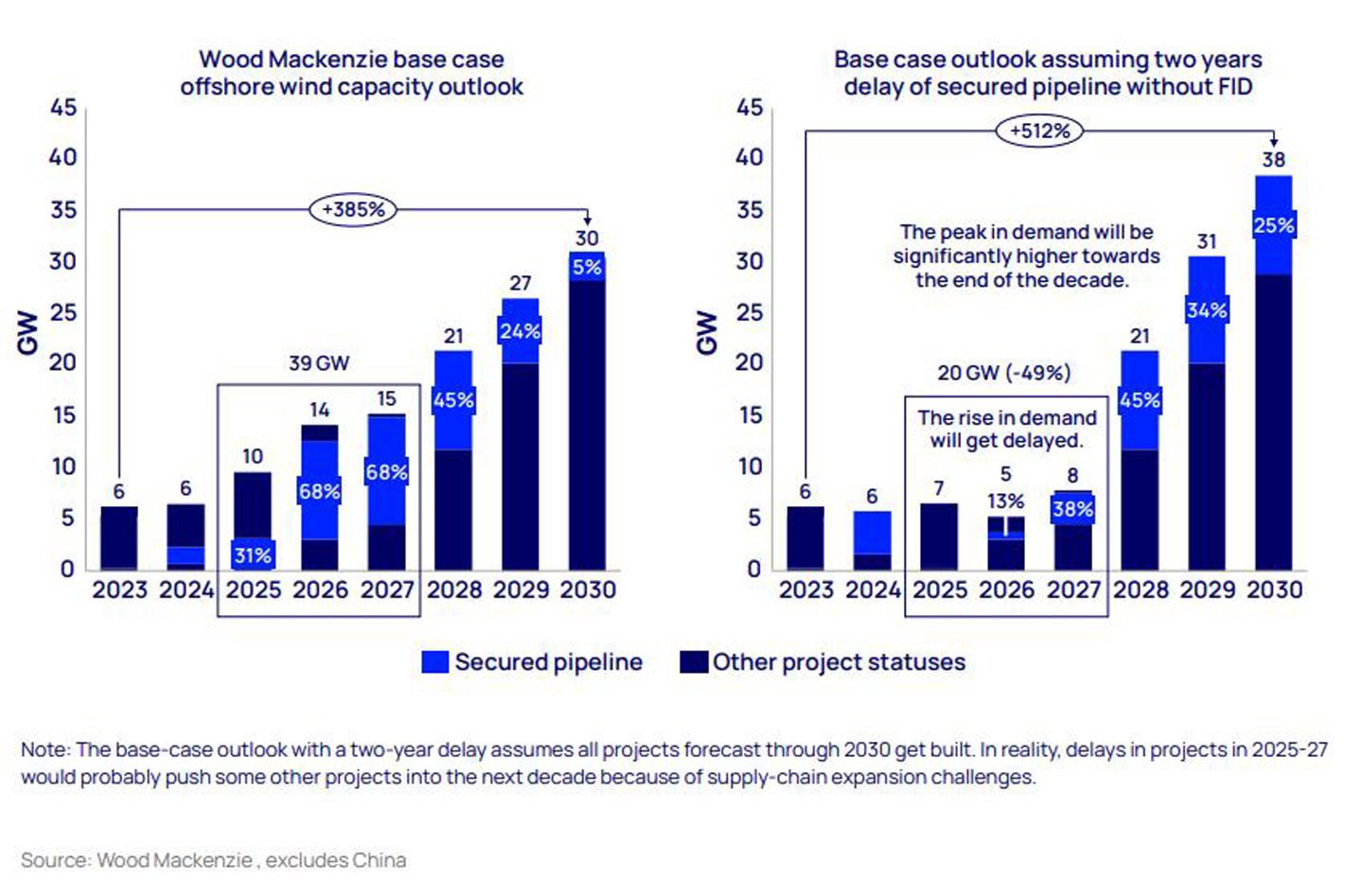

Wood Mackenzie said the crunch means certain projects risk being delayed by years, putting even greater pressure on the supply chain, with potential for governments falling even further behind on their targets.

Meanwhile, Wood Mackenzie said many investors are concerned that if the supply chain built out to meet peak demand by 2030 there would be insufficient demand for equipment after that period.

Report co-author Finlay Clark said: “This seems eerily similar to the post-2015 drop in margins across the supply chain. This is an important consideration for suppliers, in particular, as they need to be confident in the demand 10-plus years ahead to earn a return on their investment.”

In order to scale up governments and developers need to set plans for power market infrastructure to support offshore wind beyond 2030, in places where they don’t already do so.

Policymakers should also consider the impact on the supply chain when deciding whether to renegotiate existing contracts, and pausing the turbine size “arms race” with a size cap.

Wood Mac also noted its “not all up to governments” as developers need to consider innovative partnerships with suppliers to increase capacity.

Mr Seiple added: “The sector – most notably the policymakers – must take this opportunity to chart a more sustainable path for offshore wind. This will not just influence the projects being installed today or in 2030, but also the 1.4 terawatt (TW) offshore wind capacity that Wood Mackenzie expects to be connected by 2050.”

Recommended for you