Investment in the world’s electricity grids must double to more than $600 billion a year if nations are going to meet their climate targets and maintain energy security.

That would pay for adding or refurbishing about 80 million kilometers (49.7 million miles) of power transmission and distribution lines by 2040, the International Energy Agency said in a report Tuesday.

That’s equivalent to about 100 round trips to the moon from Earth.

The world needs a huge increase in electricity production, transmission and storage as population growth accelerates and economies increasingly depend on cleaner sources of energy to heat homes, run factories and power cars.

That’s becoming an increasingly political issue, as well, with governments trying to ease planning regulations while some local communities push back against more building.

Current progress on clean energy “could be put in jeopardy if governments and businesses do not come together to ensure the world’s electricity grids are ready for the new global energy economy that is rapidly emerging,” IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol said.

Doing so won’t be cheap, with governments and companies facing high costs of borrowing to finance huge infrastructure plans.

Annual investment in grids has been stagnant in recent years but needs to top $600 billion by 2030, according to the IEA’s Electricity Grids and Secure Energy Transitions.

While so much attention and money has been committed to clean power, it’s unclear whether grids are ready to handle those new assets.

At least 3,000 gigawatts of renewable power projects — nearly 30 times the generation capacity of the UK — are waiting in line for connections, the IEA said.

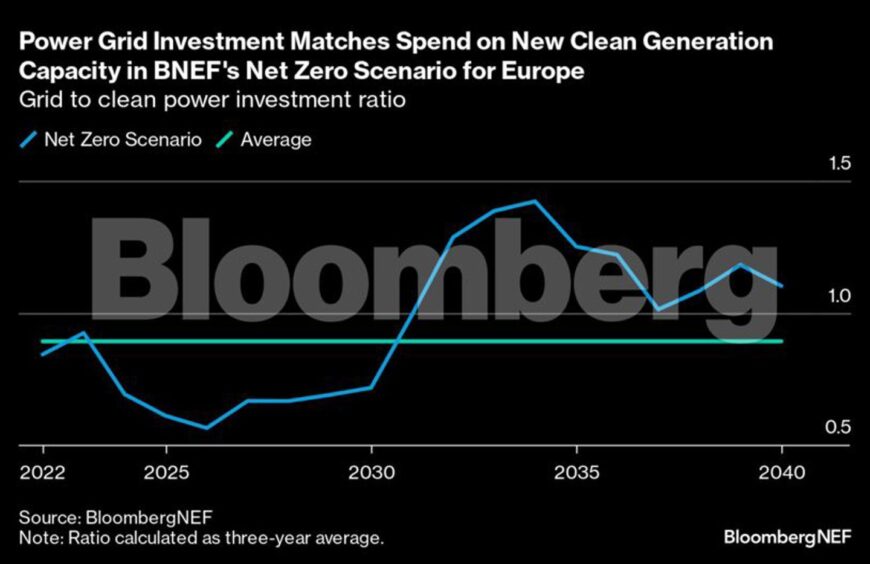

Europe’s spending on grids lags its investments in renewables and must double from current levels in order to reach net zero emissions by 2050, according to BloombergNEF analyst Felicia Aminoff.

There’s also no guarantee the poorest countries can make the required investments.

China has rapidly advanced its transmission grid and accounts for more than a third of the world’s expansion this past decade, the IEA report said.

When China is excluded, the pace of expansion in emerging economies has declined by an annual average of 7% in the past five years.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg