The wind sector is still very much in its ascendancy, but some vanguard projects are only a few years from the end of their initial design life, prompting many asset owners with the ultimate question – whether to repower or decommission?

In the more mature onshore wind sector, the implications are pressing. The UK currently has 14GW of onshore wind, though more than two-thirds of this is expected to reach the end of its operational life by 2040. Many of these sites – given they were among the first windfarms in the country – are in some of the country’s windiest locations, making them among the most productive.

“If these sites are not decommissioned and repowered, we not only lose the green power they’re producing now, but also the potential to get even more clean green energy from newer and more powerful turbines with greater capacity,” a ScottishPower spokesperson told Energy Voice.

The latter is already happening at some key projects such as the utility’s own Hagshaw site, which will be “supercharged” via repowering efforts, producing five times more power from just over half the number of turbines.

But not all sites will be suitable – life extension will be a different proposition for every asset depending on its condition and site restrictions.

Onshore repowering

The range of options for repowering range from partial – replacing turbine generators for more powerful options or with longer, lighter blades while keeping much of the main structure – to a full repower involving removal of the turbine and its foundation with a larger capacity unit. In both cases, it’s likely as much of the existing electrical infrastructure and its grid connection would be preserved.

“Most operators’ preference would be for life extension, but then there’s the questions around how economically viable will that be,” explained Lorna Bennet, a project engineer who leads the ORE Catapult’s work on the circular wind economy.

“There are two discussions we’ve been having at how they could get guaranteed income – one is through power purchase agreements (PPAs)…the other is around the growth of green hydrogen production.”

In the former case, the difficulty lies in timing. Corporate consumers may look to secure agreements a year or two ahead of delivery, while the owner of a major generating asset will want to lock in contracts as early as possible.

In the latter case, location is more of a concern – can a hydrogen production facility be located close to the wind farm to avoid transmission charges, while also maintaining its own logistical requirements to deliver the fuel to users?

ScottishPower said market support was one of the major factors in its assessment. “We focus on looking at the ability to extend the life of, or repower, our windfarms and consider a number of factors. These include operational reliability, the expected lifespan, and the opportunity to enhance the site, alongside issues such as securing a route to market,” it said.

Yet it also cautioned that the latter still presents a hurdle: “Without clear policy support, such as continued CfD eligibility for repowering projects and suitable auction parameters, there is a growing risk that existing well-sited and productive windfarms end up being decommissioned.

“If we can repower, the existing infrastructure will be decommissioned before construction can get underway. If there is not an opportunity to repower, our focus will turn to decommissioning.”

Even if market support can be found, supporting grid infrastructure could also be a major limiting factor.

“We have three or four operators currently repowering or planning to repower onshore sites. Two of them are restricted with the grid limit that they currently input, so they can’t put a bigger wind farm there,” said Ms Bennet.

“Whereas one has managed to get an allowance to increase the capacity of the wind farm they’ve just decommissioned. So, one of the main limiting factors is again back to the grid.”

Adrift offshore

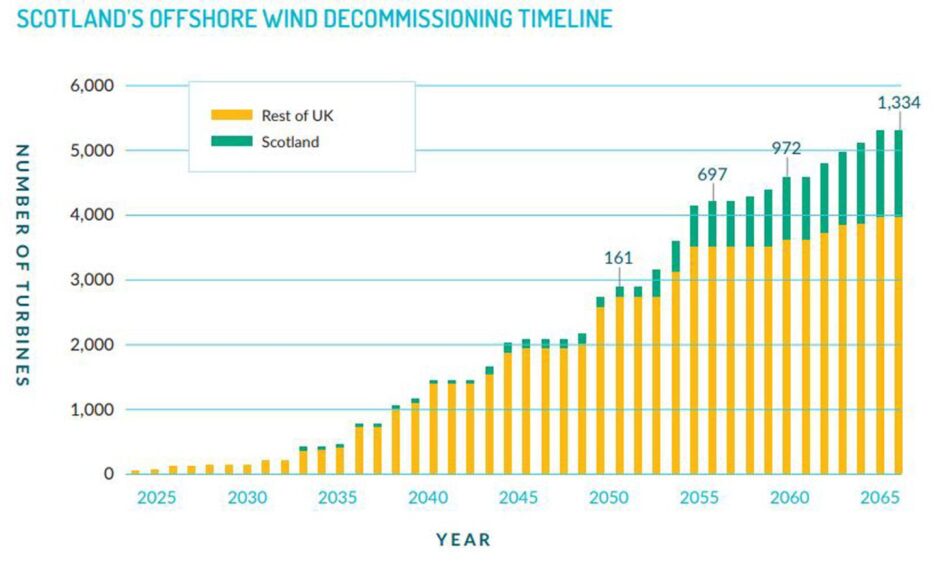

In offshore wind, end-of-life planning is further from the minds of both developers and regulators. According to ORE Catapult estimations just over 3.8 GW of offshore wind capacity in the UK is expected to reach the end of its operational life by 2035, though the volume grows significantly beyond 2055.

The regulatory process is, on the surface, similar to that in oil and gas, though it requires a Decommissioning Plan (DP) to be produced at the beginning of development alongside environmental assessments and planning consents. As in oil and gas, developers also agree a cash bond at the time of their leasing agreement as a form of security to cover decom costs.

However, the application of these documents and the frameworks in which they will be applied are to some extent untested.

“It’s a tricky one because nobody’s done it yet,” Ms Bennet noted.

“[The first offshore sites] are only just coming up to 19-20 years, and they were originally designed for 25, so we’ve still got another six years and there hasn’t been a regulatory body like an NSTA that has taken the lead on this.

“A lot of the standards have been based on taking the lead on what’s been happening with oil and gas… There has been the slow development of new standards in different places, but as far as I’m aware there’s nothing concrete done for decommissioning offshore wind yet.”

The same appears to be true of the paperwork submitted by developers. A 2020 study by University of Leeds academics reviewed a range of submitted decommissioning plans for offshore wind, concluding they “all roundly translate as effectively waiting for somebody else to take the lead in [end of life] EoL management efforts”.

Another ORE Catapult report also warned that – as has been seen in the oil sector – cash set aside to cover estimated end of life costs “can become unrealistic after 25 years or more of asset life.”

The picture is further clouded by the difference in infrastructure offshore.

“There’s additional complications in the fact that the developers build everything for the wind farm but then once it’s operational, they have to relinquish the export system to the [Offshore Electricity Transmission operators] OFTOs.

“At the moment there’s no clarity around whether the operator is going to be responsible for decommissioning the export transmission as well, or whether the OFTOs are responsible for that. So there’s still a lot of areas that are under discussion about what’s actually going to be required.”

50-year lifespan

Greater certainty has been offered for the more mature onshore sector – at least in Scotland where the planning framework makes clear that any site that has been a wind farm can remain a wind farm in perpetuity. That reassurance can make all the difference when considering life extension options.

“There’s at least three developers we know that are looking at repowering their onshore sites just now and two of them know that they won’t be able to put any more power into a site because they’re also height restricted,” Ms Bennet added.

“So they are putting in the most modern, biggest turbines they can and hope to run that for 75 to 100 years if possible – more like a traditional hydropower station – because they know that they can’t put anything better on that site.”

“It’s a complicated process and at the moment everything’s up for discussion, but I think the majority of people are wanting to look at life extension where possible,” she opined.

Offshore, these decisions are still in the works. Some clarity is given the current generation of new generation projects which are typically being built with a minimum design life of 35 years.

“The hope is that they would be able to extend the life by 15 years, so you’d get a 50-year lease out of one wind farm term.”

That’s aided by the fact the sector now has “a really clear understanding of the technology” and the environment.

“That looks far more possible than it did 20-30 years ago.”

Ms Bennet said a variety of discussions had kicked off within the past two years to developer better planning amongst developers and stakeholders such as marine agencies and the Crown Estate.

But for the moment, many questions over end of life decisions remain open – and the clock is ticking.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by ORE Catapult

© Supplied by ORE Catapult © Supplied by SSE Renewables

© Supplied by SSE Renewables