European Union negotiators struck a deal to curb methane releases from fossil-fuel infrastructure and plotted a course to monitor and limit the emissions associated with imported energy sources.

EU lawmakers and member states reached a provisional political agreement to require energy companies to regularly check infrastructure including wells and pipelines for leaks of methane, the Council of the EU and the European Council said in a statement.

The potent greenhouse gas — the main component of natural gas — has more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide during its first two decades in the atmosphere and is responsible for approximately 30% of the Earth’s warming.

#TRILOGUE | Deal! @EUCouncil and @Europarl_EN reached an agreement on a regulation to track and reduce methane emissions in the energy sector.

The regulation introduces new requirements for the oil, gas and coal sectors to measure, report and verify methane emissions.#EU2023ES pic.twitter.com/2xHPhDM0Uk

— Presidencia española del Consejo de la UE (@eu2023es) November 15, 2023

The deal is notable because monitoring, reporting and verification measures will eventually be applied to imports, which account for more than 90% of the 27-nation bloc’s oil and gas. The agreement is the latest in a series of global efforts targeting methane cuts, which scientists say is one of the cheapest and most powerful ways to reduce rising temperatures in the short term.

The new EU rules could eventually impact where it sources its oil and gas, and operators that are unable or unwilling to halt their methane emissions may find themselves with shrinking market share. Releases of methane from pipeline gas tend to be higher than for LNG, mainly due to activities in producing countries, according to Berkley Research Group.

Negotiators agreed that by 2027, importers will have to demonstrate equivalent monitoring, reporting and verification requirements at production level. After the regulations have been in force for three years, the European Commission, the bloc’s executive branch, would propose placing methane intensity classes for crude oil, natural gas and coal at the level of the producer or company.

By 2030 importers will have to pay a financial penalty for imports that are above a certain methane intensity threshold, and new supply contracts will have to take into account the rules.

The deal comes two weeks before countries meet in Dubai for the COP28 climate summit, where tackling methane is likely to be one of the main issues.

How the EU will tackle methane emissions in imports

- From 2025, energy importers will have to disclose where they get supplies from and what kind of measures exist, including whether the producer is part of the oil and gas methane partnership

- In 2026, the European Commission will publish a transparency database and create methane intensity profiles for countries; an instrument will also be implemented alongside UN to tackle so-called “super-emitting” events

- From 2027, imports will have to be aligned with the EU’s rules on monitoring, reporting and verification; the commission will also publish methodology for measuring methane intensity

- In 2028, importers will have to show how methane-intensive their imports are

- From 2030, penalties will be issued for imports that are above a methane intensity threshold

“The extension to imports, which was my main priority in the parliament’s position, will have repercussions worldwide,” said Jutta Paulus, the green lawmaker who led negotiations from the European parliament. “I am very pleased that we will go to the UN climate conference in Dubai with full hands.”

Methane is the primary component of natural gas but it also leaks across coal and oil supply chains, sometimes without the knowledge of operators. However, producers do often choose to release the gas into the atmosphere if it’s more expensive to contain than trap and bring to market.

“Considering the prospect of an import standard was nothing more than a dream a year ago, this outcome is a major step forward,” said Brandon Locke, Europe policy manager for methane pollution prevention at Clean Air Task Force, a climate non-profit.

“While we would have preferred a faster timeline to reduce emissions before 2030, this agreement will nonetheless go a long way to dramatically cut global methane pollution.”

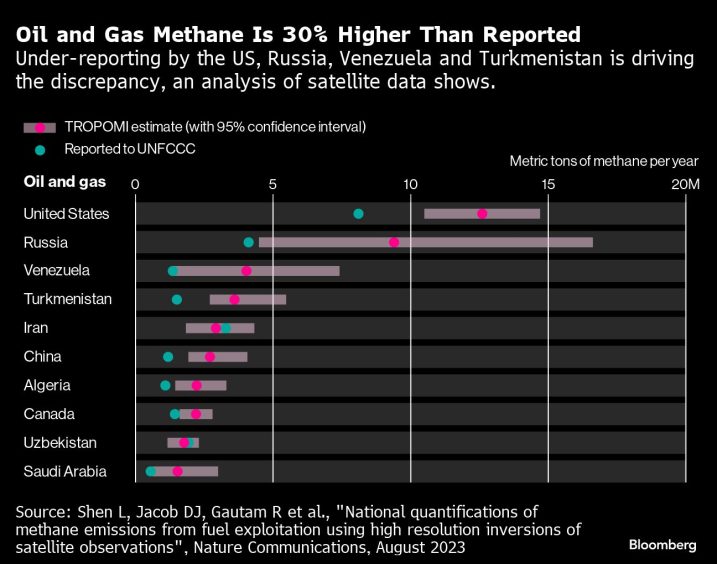

Scientists using satellite observations have consistently found that operators and governments significantly under report methane emissions from fossil fuel production. A study published in Nature Communications in August that relied on satellite observations found that observed methane releases from global oil and gas operations are 30% higher than estimates provided by countries to the United Nations.

The world’s four largest oil and gas emitters — the US, Russia, Venezuela and Turkmenistan — account for most of the overall discrepancy, according to the report.

China, the world’s largest emitter of methane, said earlier this month it will boost monitoring, reporting and data transparency to reduce releases of the greenhouse gas. American officials were negotiating a deal to help Turkmenistan curb its vast methane emissions, Bloomberg Green reported in June.

Recommended for you

© Bloomberg

© Bloomberg