Sea trade is under massive pressure to change as the global population of 61,000 ships collectively weighing in at over 2.1 billion tons deadweight is responsible for over 3% of current CO2 emissions and still rising.

Two years ago, the World Bank ranked it as the “sixth largest greenhouse gas emitter worldwide, ranking between Japan and Germany”.

But how to turn this staggering diesel and heavy oil-guzzling juggernaut around is a massive challenge as there are currently very few vessels fuelled by alternatives.

We covered nuclear in January, but what are the other options?

Speaking at the DNV Maritime Shipping Energy Transition Summit last month, the influential classification body’s maritime chief executive officer Knut Ørbeck-Nilssen told the industry that the clock was ticking with just seven years before it hit the first major carbon footprint reduction hurdle.

“As we all know by now, global decarbonisation targets became more ambitious last summer. Shipping’s target is now a 20% reduction in emissions by 2030, 70% reduction by 2040 and full decarbonisation by or around 2050,” he warned.

“We’ve also seen implementation of the EU’s ETS (Emissions Trading Scheme) on shipping from January 1 this year, further raising the stakes.”

However, the drive for decarbonisation is not just coming from regulations.

Ørbeck-Nilssen: “More and more we are seeing demands for a greener maritime industry from stakeholders within the maritime industry’s value chain.

“Cargo owners are a key force in this regard; they are listening to their customers and to society at large and understand their responsibilities and obligations to make the (maritime) supply chains greener.

“And, in turn, they expect their maritime partners to help them achieve this.

“This increased pressure really crystallises things and challenges us to come up with both short-term and long-term decarbonization solutions.”

This begins with analysis of fuel availability and DNV last year warned that the maritime industry and those forcing it to slash its carbon footprint must not ignore the reality that the supply of alternative carbon neutral fuels is nowhere near where it needs to be to reach short-term emissions reduction targets let alone long-term.

“Our latest maritime forecast estimates that shipping would need 30-40% of the global supply of carbon neutral fuels if we are to reach the IMO’s 2030 target,” said Ørbeck-Nilssen

“Now, that is as most of us can understand, highly unlikely, bordering on the impossible.”

Classification societies like DNV and Lloyd’s Register, Bureau Veritas and the American Bureau of Shipping report promising growth in the number of new and retro-fitted vessels which will be able to run on alternative fuels, whether ammonia, methanol, hydrogen, biofuels or something else and carry banks of batteries for in-port idling.

Interest in biofuels is also increasing and this could become a key component of decarbonisation of existing fleets.

This is a great step in the right direction and we expect these numbers to continue to grow, the reality is that, even if the technology is in place, the shipping industry is a long way from being able to access the huge volumes of carbon-neutral fuels needed to operate the global fleet.

Ørbeck-Nilssen told summit delegates they must also accept that these new fuels come at a premium to traditional fuels; at least for now.

“It is also uncertain as to which fuels will eventually be the ones that break through and succeed in making investment decisions even more difficult for shipowners.

“So how can we reduce emissions by 20% by 2030 if we haven’t enough alternative fuels? This is a key question. And the answer is we need to look beyond fuels and this starts with energy efficiency.”

The reality is that a range of practical, effective technologies is available today which can improve the energy efficiency of vessels, decrease net energy input and achieve significant reductions in emissions.

One of the possibilities is wind assist and this has apparently captured the imagination of many maritime industry decisionmakers.

Who would have thought that after all these years of technological development we would use sailing ships again?

“Now this is an exciting, practical solution to the decarbonisation puzzle and a testament to the fantastic innovation taking place,” enthused Ørbeck-Nilssen.

“There are other energy saving options in abundance … air lubrication systems (basically this means streamlining), solid oxide fuel cells, machine efficiency improvements, waste heat recovery and so forth.”

Digitalisation is also playing its part, making fleets smarter and maximising efficiency.

Shipowners need to thoroughly examine these technologies and decide what the best fit is for their own fleet.

Once this is done they should make sure that they develop a long-term decarbonisation plan that has energy efficiency at the core.”

This is not pie in the sky, real momentum is building, albeit slowly. 2023 was hugely important in this regard.

According to analyst Steve Gordon, head of the research arm of the world’s largest shipbroker, Clarksons of London, the shipping juggernaut is altering course towards decarbonisation.

In a research note summarising progress for 2023, Gordon records:

- There were 539 newbuild orders involving alternative fuel-capable vessels, 45% of all orders placed by tonnage.

- The largest share of alternative-fuel orders for the year was still LNG (liquefied natural gas) dual-fuel (220 orders of which 152 were non-LNG carriers), albeit with an increase to 125 orders of methanol dual-fuel vessels.

- There were 55 new orders involving LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) as a fuel and four capable of burning ammonia (NH3).

According to DNV’s Maritime Forecast to 2050 analysis, although there are ongoing demonstration projects for ammonia-fuelled ships, there are none in the official order book.

The report says that using ammonia as a ship fuel requires the continued development of suitable energy converter technology, which is still a few years into the future.

Furthermore, the lack of prescriptive rules and regulations for handling ammonia is making it difficult to plan for its implementation on board.

This lack of regulatory development is also causing issues for the adoption of hydrogen as a fuel.

Indeed there are so far only two operational vessels – one in Norway, the other in China.

The entry into service of the MF Hydra, ferry powered by proton-exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells fuelled by liquid hydrogen a year ago marked a significant advance for what remains a largely untried technology.

Launched during the China Green Energy Development Conference in the city, also a year ago, the 49.9m vessel, known as Three Gorges Hydrogen Boat No. 1 is employed in the Three Gorges reservoir area for transportation, patrol and emergency response.

The above-noted implementation barriers come in addition to the challenges currently applicable to most carbon-neutral fuels: increased capital investment, limited fuel availability, lack of global bunkering infrastructure, additional training of crew, high cost of fuel, and additional demand for storage space on board.

The uptake of vessels capable of operating with ammonia as fuel is expected to pick up once the technology becomes available, supported by the fact that 58 ships in DNV Class have been ordered

as ‘ammonia ready’, implying that some preparation for potential conversion to ammonia propulsion has been done at the new build stage.

Returning to the Clarksons’ take on the 2023 decarbonisation progress, Gordon noted:

- Reflecting future “optionality”, there were 579 in fleet and newbuilds with “LNG-ready” status, 322 classed as being “ammonia-ready” and 272 categorised as “methanol ready” (CH3OH).

- Take-up varied across shipping segments, with 83% of containership newbuild capacity ordered, rising to 94% including orders with “ready” status; and 79% of car carriers (98% including “ready” orders) ordered with alternative fuel capability but much lower shares in bulk carrier and tanker.

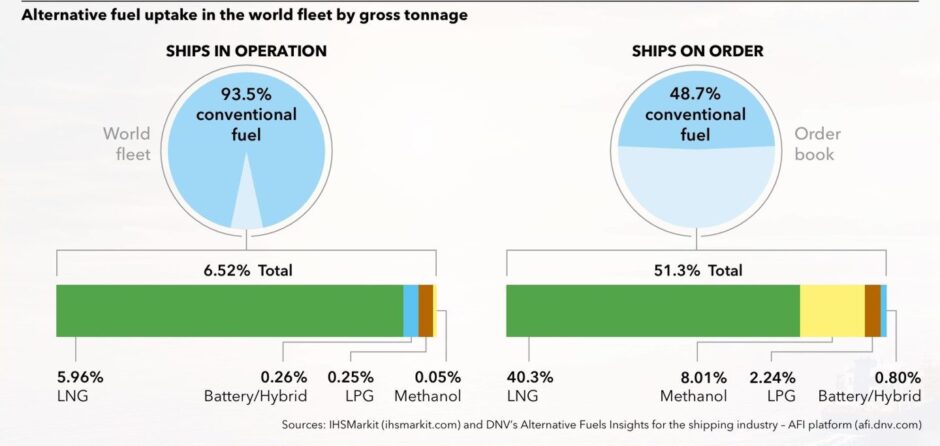

- Overall, at the turn of the year, 6% of global fleet capacity was classed as alternative fuelled capable (up from 2.3% in 2017), which Clarkson’s projects will increase to nearly a quarter of all fleet capacity by the end of the decade (2030), around 23% of global fleet capacity.

- The Clarkson’s Green Technology tracker also included 31 in-fleet vessels (plus 22 new builds) testing onboard carbon capture technology.

Further, Gordon reported other important developments, with “eco” vessels now constituting 32% of global tonnage on the water (as high as 50% in VLCC and Capesize ships), with the use of innovative energy-saving technologies continuing to expand.

At the turn of the year, Clarksons recorded 7,295 vessels in the global fleet as having “significant ESTs”, including 47 with wind assist.

And, in terms of cleaning up emissions, Gordon said: “Our tracking of SOx (sulphur dioxide) scrubbers has also increased year-on-year; totalling, including pending retrofits, over 5,590 vessels in the fleet … 27% of global fleet capacity.”

He added that 420 vessels were retrofitted with scrubber systems last year and 321 new ships on order have scrubbers specified.

Clarksons also estimated that over 80% of global tonnage is now fitted with a ballast water management system.

This is a classic passive measure as it has been known for centuries that a properly ballasted and trimmed ship is more efficient and safer than one that hasn’t been afforded such attention.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by DNV

© Supplied by DNV © Supplied by DNV

© Supplied by DNV