Just as they first ventured to do over a century ago, the world’s largest oil companies are staking claims far from home — this time to swallow, rather than spew, planet-warming industrial emissions.

Carbon dioxide storage is emerging as a potential multi-billion-dollar revenue stream for firms like Exxon Mobil Corp., Shell Plc and Chevron Corp., which are under global pressure to rein in the unfettered burning of fossil fuels.

In Asia, which will generate the majority of this century’s carbon emissions, Indonesia and Malaysia are among the few places where CO2, once captured, can be viably stored underground. With the cash, decades of experience injecting carbon for the purposes of pumping extra oil, and an increasing number of depleted wells that can be refilled, oil companies are already jockeying for position.

Exxon Mobil Chief Executive Officer Darren Woods said the company has “secured exclusive rights to CO2 storage” in Indonesia and Malaysia. “World-scale problems like climate change need world-scale companies to help solve them,” he told business leaders at a San Francisco summit in November.

Shell has signed an agreement to scope out possible sites with Malaysia’s national oil company, Petronas. Chevron is studying a project in Indonesia. And France’s TotalEnergies SE is actively exploring storage potential in the region.

Meanwhile, Indonesia’s government last month rushed through a presidential decree on possible incentives for CO2 storage operators. Similar schemes are underway in Europe and Australia.

“There’s a race,” said Lein Mann Bergsmark, head of carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) research based in Norway for consulting group Rystad Energy. “More and more oil and gas companies are dedicating efforts to acquire pore space or rights to store CO2 all around the globe.”

Storage is the final step in the process known as carbon capture and storage (CCS), a technology designed to suck CO2 out of the atmosphere and bury it underground forever, in theory neutralizing its effects on climate change.

For oil companies, the wide deployment of CCS is a lifeline, albeit a thin one: It means they could preserve up to 20% of today’s oil and gas demand through 2050 without pushing global warming beyond levels set in the Paris Agreement, according to the International Energy Agency. Without it, consumption would need to fall even further. It also provides a new source of revenue, as companies can rent out storage space for a fee.

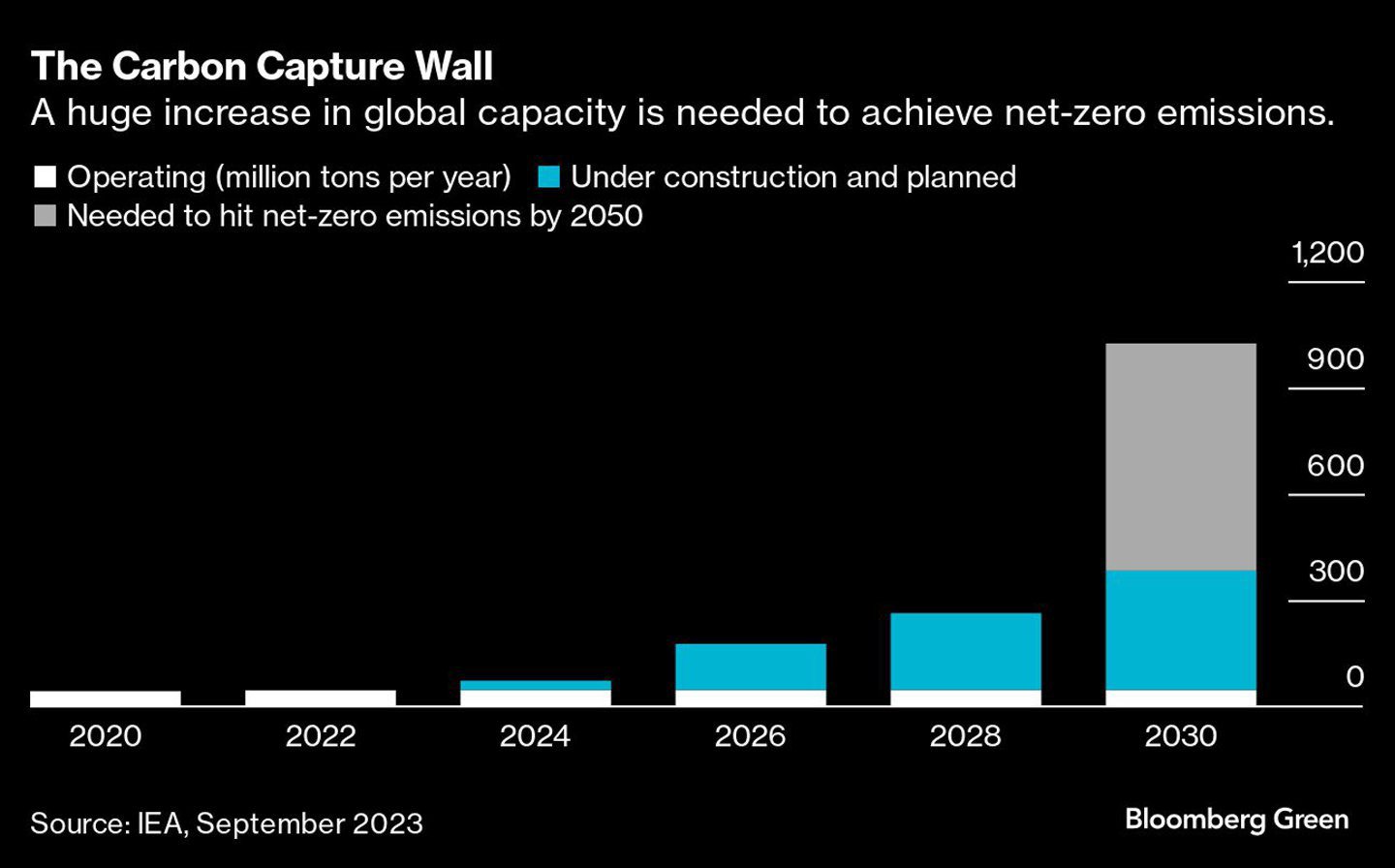

For now, there’s a huge gap between the amount of CO2 that will need to be captured and the storage space that’s available. To meet global climate goals, more than 1 billion tons of CO2 will need to be sucked up and buried every year by the end of the decade, according to the IEA. But today only 4% of that capacity is available across just a few dozen commercial sites globally.

Part of the problem is economics. At the high end, it can cost more than $1,000 to capture and bury a ton of CO2, depending on the source of the gas. Absent a strong price on carbon emissions, oil companies have yet to make even lower-cost capture and storage projects financially viable.

Then there’s the politics. In the US, fierce pushback from environmentalists and local residents has delayed storage-well permitting and construction. In a public hearing last summer, dozens argued that state regulators were ill-equipped to oversee the injection wells, warning about the risk of lax oversight and ruptures.

Geology also is a constraint. There are two types of underground space that can be filled with carbon dioxide — deep, permeable rock formations called saline aquifers, and old, depleted oil and gas wells — and they don’t exist everywhere. In Asia, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore are all heavy emitters, but they lack the subsoil characteristics to permanently sink enough CO2, meaning they’ll need to export it to elsewhere in the region for burial, analysts say. Singapore recently appointed Exxon and Shell to help it scope overseas sites.

Indonesia and Malaysia, meanwhile, are being earmarked as suitable repositories — a plan the two governments have, so far, endorsed.

Big regional emitters “come and see us,” said Emry Hisham Yusoff, head of the carbon management division at Petronas. “What they want is assurance that there’s storage.”

The two countries of course have their own emissions to capture and bury too, a challenge that’s prompted Jakarta to state that 70% of Indonesia’s potential storage space will be reserved for domestic emissions.

“You can think of Korea or Japan as huge markets that are looking for homes for emissions,” said Chris Stavinoha, Chevron’s general manager for CCUS solutions in the Asia-Pacific region and the Middle East. The company anticipates “significant interest” in the limited space available, particularly in southeast Asia, he said.

Rystad estimates that CO2 transport and storage in southeast Asia may generate about $16 billion of annual revenue by 2050, though it depends on how much the region can sequester, and projections vary widely.

Exxon signed an agreement last year with Indonesian national oil company Pertamina to develop a $2.5 billion storage facility. TotalEnergies is investing about $100 million per year in global CCS development, a figure that may triple by the end of the decade, said Etienne Anglès d’Auriac, the company’s vice president of CCS.

For some analysts, the emphasis on storage is misplaced in light of the current state of carbon capture. Some of the biggest and most advanced attempts are struggling or have failed outright. If capture does work, there still aren’t many ships available to transport CO2. Suitable storage sites are rare and take years to identify. Even then, history suggests they’re far from reliable.

Read More: Big Oil’s Climate Fix is Running Out of Time to Prove Itself

There’s a chance there won’t be enough CO2 captured to fill all the wells, said Mhairidh Evans, head of CCUS research at energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

“One narrative is there’s this big gap on storage, whereas our take is there’s a gap on capture,” she said. Big oil companies “see this as a natural evolution of their business, as a revenue generating opportunity, but what’s much murkier is the myriad of industries that have to actually come on board and capture that CO2 in the first place.”

To encourage the market, oil companies are leaning on governments to accelerate permits for storage and to subsidize the cost of developing those sites. Exxon, Chevron, Shell and TotalEnergies all told Bloomberg that they’re working with the respective governments to help shape the rules governing the sector.

Days before last month’s general election in Indonesia, the government issued a presidential decree offering financial incentives to companies seeking to build storage facilities for imported carbon. The companies will be able to apply for permits that are valid for up to 30 years. How much the projects will generate in taxes and royalties is still under discussion, a government spokesperson said.

Malaysia, meanwhile, has no clear legislation for importing CO2, said Emry at Petronas, which is looking to develop three storage hubs that together would be capable of storing up to 15 million tons of CO2 per year by 2030. “There’s a lot of push” to expedite this, he said. “We’re trying to learn from each other here.”

The ministry of economy is conducting a “comprehensive study” on CCUS development and Malaysia is aiming to have draft legislation on CO2 imports and storage in the first quarter of 2025, a ministry spokesperson told Bloomberg. The country expects it has more storage space than it needs and renting that to others will reduce the need for government subsidies.

“If you want to try and build a business model that is underpinned by a regulatory framework that is supportive of CCS, then both sides have to actually start talking,” said Yu Li P’ing, general manager of CCS for the Asia-Pacific region at Shell. “Getting both industry and government to come together has really picked up in the last few years. The momentum has grown and continues to grow.”

Recommended for you

© Bloomberg

© Bloomberg © Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg © Bloomberg

© Bloomberg