Technology that addresses methane emissions has historically been overlooked compared to strategies that cut carbon dioxide, but that tide may be shifting.

Startup Windfall Bio has raised a $28 million Series A led by Prelude Ventures to scale its methane-capture technology, with a bevy of high-profile investors onboard, including Amazon’s Climate Pledge Fund and Breakthrough Energy Ventures.

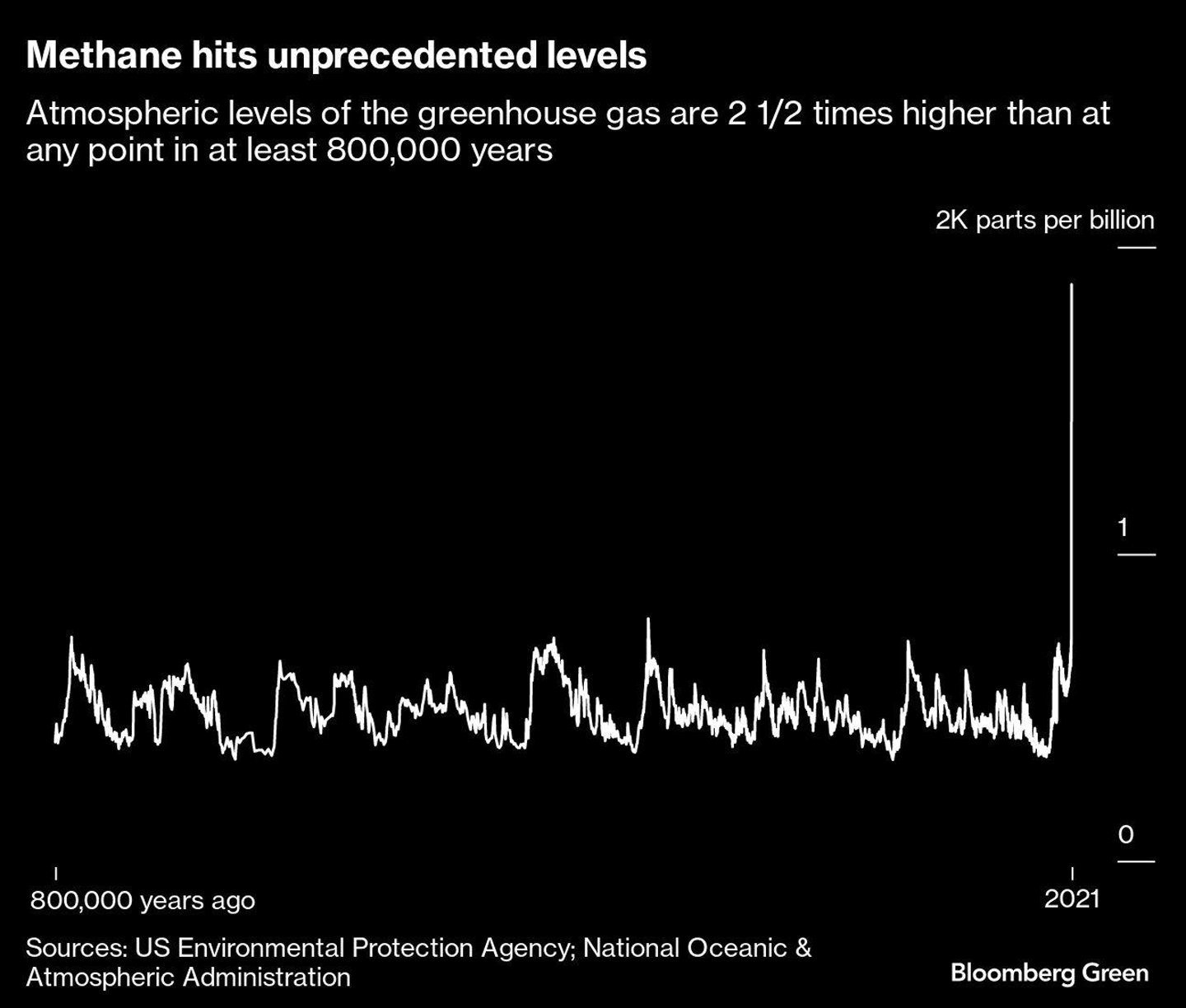

Methane is about 83 times more potent than CO2 over its first 20 years in the atmosphere. While some of the world’s biggest oil and gas producers have pledged to significantly cut methane emissions by 2030, the biggest anthropogenic source is agriculture, particularly beef and dairy production. Those emissions have proven hard to avoid.

“It’s particularly hard because agriculture is so important, and we all need to eat,” said Stephanie Díaz, an associate on BloombergNEF’s technology and innovation team. “But it’s such a diffuse set of producers who are working on thin margins, [so] it’s hard to get change when that’s your market condition.”

Methane-eating microbes

That’s where Windfall hopes to step in. Founded in 2022, the San Mateo, California-based company sells methane-eating microbes, or mems, to big methane producers, including farms, waste treatment facilities, landfills, and oil and gas producers. In addition to destroying methane, the process also produces organic fertilizer. The startup is currently piloting its technology with customers that include Whole Foods, which provides Windfall access to its network of dairy farmers.

Methane “has been a huge blindspot,” and mems can be one way of transforming the harmful emissions into a useful substance and revenue stream, said Windfall co-founder and Chief Executive Officer Josh Silverman.

He compared the microbes to yeast; mems like to eat methane the way yeast likes to eat sugar. Windfall’s mems use energy from the methane they eat to pull nitrogen out of the air, creating an organic fertilizer that customers can use on their own farms or sell for profit.

Agriculture methane

The technology is best suited for enclosed sources of methane, such as a dairy farm’s barn, tarp-covered manure lagoon or enclosed feedlot, where gas from the source can be easily vented out and treated. In an oil and gas facility, that might look like diverting a pipe of methane that otherwise would have been flared. In a landfill, it could mean taking methane from a well drilled into the structure or from cracks and leaks in the landfill cover. While Windfall is working with companies in those industries, it declined to share specific customers outside Whole Foods.

At dairy operations, farmers can spread mems over a compost pile. The methane from the barn, lagoon or feedlot can then be piped over to the treated compost. For customers without access to direct compost, they can grow mems on any solid, inert surface, such as biochar or even plastic beads in a fiberglass tub, which can be reused. In the latter case, the transformed cells can be sprayed off and dried down into a high-nitrogen paste.

Read more: Farming in a net zero world

That process leaves out two other big sources of emissions: rice paddies and cattle left out to graze. Mems can pull methane out of the ambient air, Silverman said, but the economics are tougher because of how diffuse the methane and nitrogen are, as well as the difficulty of recovering the fertilizer once it’s created. Other startups are working on addressing those sources of methane emissions, with solutions ranging from feeding cows additives like seaweed to not-yet-commercialized vaccines and breeding.

Oil and gas methane

When it comes to oil and gas leaks, another major source of methane emissions, oftentimes the solution is very low tech: Repair the leaky pipe. But that doesn’t address emissions from intentionally flared gas, like the type that’s ticked up in Texas’s Permian Basin despite investor pressure to curb emissions. Instead of flaring, oil and gas producers could transform the methane emissions into organic fertilizer and sell it to neighboring farms, generating a profit, Silverman said.

Selling or using the fertilizer locally would be key to making this a profitable solution, since organic fertilizer is hard to store and transport compared to its synthetic alternative. It’s also typically more expensive. But Windfall is banking on rising regulatory pressure and issues associated with ammonia usage, such as groundwater contamination, to spur more widespread organic fertilizer adoption.

Silverman said that fertilizer made with Windfall’s mems is 50% cheaper than conventional organic fertilizer, and that the company’s main challenge now is keeping up with demand. That’s why the fundraiser came so quickly on the tail of Windfall’s $9 million seed round last year, he added. The company’s focus for the year ahead is scaling up its manufacturing process to start supplying commercial quantities of mems in 2025.

© Supplied by Bloomberg

© Supplied by Bloomberg