Much writers ink has been spilled on the severity of the skills shortage facing an otherwise resurgent global oil and gas sector. The figures are stark, and speak for themselves. The average age of oil and gas workers – at 56 – is astonishingly high relative to almost all other industries on the planet. Nearly half the industry workforce is now over 45. And the shortage is most severe where the industry can least afford it to be – highly skilled, technical roles out in the field, crucial to any project. Of the total pool of experienced engineers within the industry, over half will be eligible for retirement in the next five to ten years; a sobering statistic for anyone with an interest in the future of the industry (which, to be frank, is everyone).

This shortage – predominantly of mid-tier employees in the 35-50 age range, with around a decade’s worth of experience – is in part the price the industry is paying for the shutdown of recruitment and training programmes during the oil price slump in the 80s. Until now, companies have largely muddled through regardless, buoyed by a return in demand. But the demographic conveyer belt will come to an end sooner rather than later. What’s more, the industry will soon need a major influx of people if it is to cope with ballooning demand from emerging markets (not to mention the potential impact of shale gas extraction taking off outside of the US). It is estimated that the global oil and gas industry will need over 120,000 new workers to plug the gap over the next decade.

Fast-tracking younger employees and graduates through training schemes will play a big part in the solution. Making effective use of industry veterans in a mentoring capacity will also play a vital role at the other end of the spectrum. But given the scale and immediacy of the crisis, these solutions alone will not suffice. In order to adequately rise to the skills challenge, the industry needs to look sideways, and recruit candidates with the relevant transferable skills from other sectors.

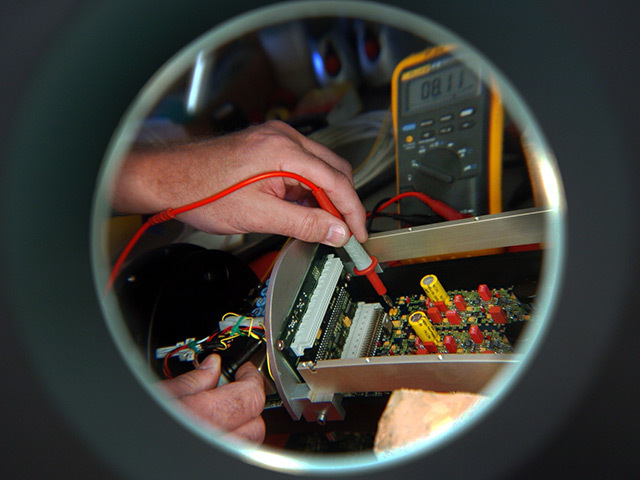

So far, so simple – after all, sideways recruitment is an everyday fact of life in many other industries. However, the oil and gas sector has historically – and understandably – been reluctant to do so. This is an industry where multi-million pound projects reliant on multi-million pound pieces of very sensitive, technical equipment are routinely placed under the responsibility of a relatively small number of highly specialised employees. So the oil and gas industry has more incentive than most to want to ensure its workers are ‘proven assets’, with mountains of previous hands-on experience in that precise field.

Now the time is fast approaching – if it isn’t here already – when relying solely on candidates with direct experience simply isn’t an option. There are sectors out there that the oil and gas industry would do well to tap more thoroughly for talent. So where should companies be looking?

The main priority for oil and gas businesses when it comes to these skilled roles is usually practical experience as opposed to pure technical know-how. Firms want ‘field-tested’ candidates, who have used the equipment, run successful projects, and have encountered and overcome the thousands of pragmatic and logistical niggles, set-backs and malfunctions that can plague such projects. So the key for successful, cost-effective sideways recruitment is to find such ‘field tested’ candidates from sectors where the jump across in terms of retraining for a new environment or new equipment is minimal.

The mining industry is one of the more obvious sources of such talent. As with oil and gas, its engineers are often out in the field, in inhospitable, high-pressure environments. In a lot of cases they will be dealing with very similar equipment to that used in onshore and offshore oil and gas extraction (such as turbines). Countries such as South Africa that have both large energy and mining sectors have made use of the overlap for some time.

However some promising pools of talent are a bit less obvious: for example, the military. The Army, Navy, and Air Force are full of potential recruits with relevant transferable skills. These are people with plentiful experience operating all manner of specialist aircraft and vehicles – or people with deep experience of managing logistical issues, with getting the right people to the right place at the right time under pressured, time-sensitive conditions. All of which can be useful depending on the project in question. For instance, a lot of current and future development in oil and gas is underwater, down at the sea bed. Recruits can often be found in the Navy with skills relevant to subsea environments such experience with remotely operated vehicles (the jump from using such technology for salvage missions to using it to fix malfunctioning equipment is minimal). Similarly, a pilot’s experience of flying specialist aircraft in desert conditions may be of particular use for a firm looking to develop a new oil field in some far-flung onshore location. The military is also fertile ground when it comes to finding recruits with relevant mechanical and electrical engineering skills, and with experience of operating in hostile environments. Marine engineering staff from the merchant service already find roles in production plant operations and maintenance, non-destructive testing and certification, but still represent an underused resource.

The wider energy sector is also less appreciated than it should be as a source of transferable skills. The nuclear sector, for example, is steeped in experience when it comes to decommissioning old plants. Decommissioning platforms and wells from depleted fields is also a major part of the oil and gas lifecycle, so there is a natural overlap here. Indeed, the refitting and re-commissioning of plants to cope with changes of feedstock, handling flows from competitors due to changing pipeline sharing arrangements over time, changes to oil/water ratios over the life of operating fields and to recovery enhancements, could all fall within the skills scope of employees with decades of experience in the nuclear sector. Similarly, the renewables sector has plenty to offer in terms of project managers, engineers, and technicians with experience of managing high and low temperatures and pressures, working with turbines, transporting materials, carrying out major installations and so forth.

Increased sideways recruitment would be a quid pro quo, bringing benefits to both the oil and gas industry and to those candidates making the crossover.

In terms of the benefits to oil and gas businesses, one of the big obstacles to solving the skills shortage is commercial concerns regarding the cost of training programmes for graduates and new recruits. Not just the up-front costs of the training itself, but the danger that, once trained, employees will be snapped up by rivals offering a marginally better remuneration package – effectively meaning that firms run the risk of subsidising the training costs for competitors. A well-judged sideways hire can mitigate this risk by reducing the amount of training needed in terms of cost and time. For an analogy, compare the cost in time and money for a law degree, as opposed to a conversion course.

A wider pool of candidates would also itself be beneficial to the industry. A smooth, profitable project means finding the right people quickly, and adequately managing risks related to this throughout. People risk is a big deal in the oil and gas sector due to its global, project-based nature, as well as its strict health and safety requirements. A larger pool of relevant candidates to draw from mitigates people risk, and will reduce overall labour costs in the long run. With oil prices so high this may not be the foremost consideration right now, but at some point in the future prices are bound to fall again for one reason or another, squeezing margins. It goes without saying that a company reducing costs associated with staff employment now will be in a far better position to see through poorer market conditions when they come.

As for the candidate making the jump across to oil and gas, the proposition will usually be a very attractive one. It is likely that they will enjoy a far greater earning potential and more opportunities to travel than their previous industry could offer. And it’s not just a matter of superior material benefits; a lot of the current activity in oil and gas, such as the aforementioned development of new subsea extraction techniques – is at the very forefront of engineering, technology and science. Curious minds and able engineers will often find a far greater and more satisfying intellectual challenge in oil and gas than they might find in other areas.

Andrew Speers is managing director of Petroplan

Recommended for you