Oil and gas watchers can’t fail to have noticed a wave of ‘megamergers’ across the pond as established players have bolstered their future production pipelines through major acquisitions, with eye-catching numbers.

Our stateside cousins smashed all records in Q4 2023 with deals totalling a staggering $144 billion and backed this up with a further $51 billion in transactions in Q1 this year, according to energy analysts Enverus Intelligence Research.

The biggest trades were Chevron, announcing it would acquire Texas oil company Hess for $53 billion in October (arbitration hearing pending), and ExxonMobil’s merger with shale group Pioneer Natural Resources valued at $59.5 billion, which finally crossed the line in May.

Closer to home, Harbour Energy announced a reverse takeover of German oil and gas firm Wintershall Dea for $11.2 billion in December – adding 1.1 billion barrels of oil equivalent in reserves and consolidating the London-headquartered independent’s position as a genuine global player.

This, I believe, is a bellwether for deals to follow.

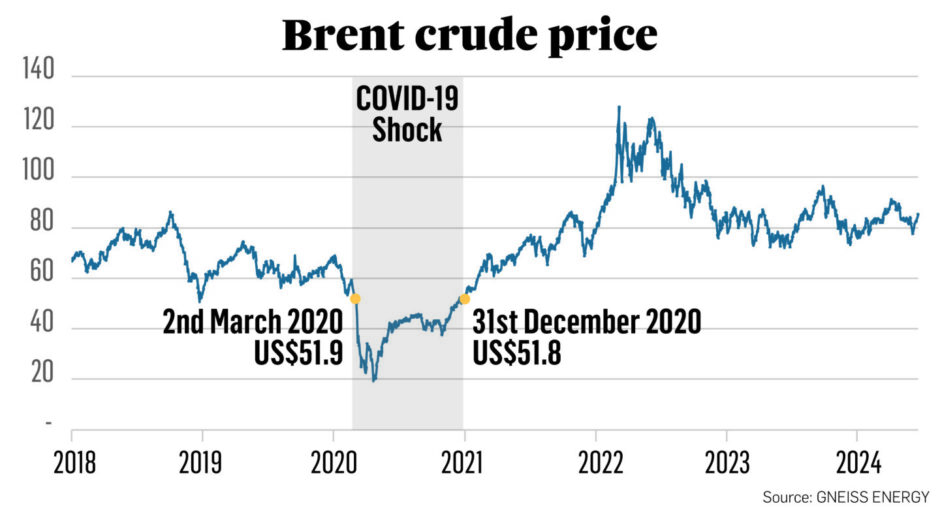

For nearly a decade, European supermajors have dialled back investment in their upstream business – driven in no small part by ESG pressures from its shareholders and governments, rebranding and a lurch towards investment in renewables – despite (Covid aside) the oil price remaining relatively high and stable for the last five to six years, and with global demand for oil and gas continuing to rise.

In the ‘normal’ cycle, this high oil price would have sparked upstream investment and all would be well – but the factors above have left some majors on the horns of a dilemma, having dropped the ball on reserve replacement and the prospect of shareholders demanding a return that will not be met by a renewables pipeline coming onstream far slower than hoped.

Return to consolidation

In the UK at least, new hydrocarbon exploration is looking perilously close to being off the table, and even further development drilling is unlikely to be sanctioned by sector participants under the new Labour administration.

The Westminster government will likely obfuscate the destructive nature of their domestic hydrocarbon policies by pointing to some short to mid-term M&A transactions in the UK. But those in the know will understand that this will likely be driven by companies looking to rationalise their tax position, rather than investing new dollars in the UKCS.

Contrast this with the US, where the front half of 2024 has seen no let-up in the return to consolidation in the oil sector that kicked off in 2023.

Chevron and ExxonMobil have gone in hard with both boots to buy substantial portfolios of low-cost assets (in the face of pushback from some stockholders), followed closely by fellow stateside energy conglomerate ConocoPhillips announcing plans to buy Marathon Oil in an all-stock deal worth about $22.5bn – placing another vast bet on the future of fossil fuel production.

These deals will cement their respective positions as dominant publicly listed upstream powerhouses, converting the valuation gap they enjoy – versus their European counterparts – into a looming production, revenue and operational capacity chasm.

As analysts Wood Mackenzie identify in their international E&P benchmark report, consolidation has been key in building scale, stating: “Size matters: larger players are more resilient with greater capacity to manage volatility,” provided that mergers build on (or maintain) financial strength.

In the end, these US megadeals highlight a challenge for shareholders in their European equivalents, who may demand solid returns alongside a cleaner energy portfolio.

Stateside supermajors are betting that oil and gas will be with us for quite a time to come, and to quote a colleague: “you can’t ‘just stop oil’ until you just stop oil demand”.

So, as long as demand remains, there are major firms US willing to step up and meet it.

Whether the European majors wish to jump in too – and do the major deals they need in order to compete – will play out in the months ahead.

Recommended for you