UK carbon capture and storage (CCS) developers outside of the track-1 process need certainty from the government “before Christmas”, according to an industry body.

Carbon Capture and Storage Association (CCSA) chief executive Olivia Powis said investors and track-2 initiatives “urgently” need to see clear signals of support after just two projects were allocated £22 billion by the UK government.

Speaking to Energy Voice, Powis called for the introduction of regular funding rounds for CCS like the UK government’s current contracts for difference (CfD) scheme

“We’ve been caught in an election year which has caused an enormous delay to progress for those projects,” Powis said.

“For projects outside of track-1 they absolutely need certainty, and they need it very soon.

“We’re very much pushing for clear signals and directions in terms of what the process will be, which projects will be selected as anchor projects… and we need to see that in the next few weeks before Christmas.”

Track-1 and Track-2 CCS clusters

Last month, the Labour government confirmed £22bn in funding for two major CCS projects in the North of England.

The previous Conservative government selected the HyNet and East Coast Cluster projects for its ‘‘track-1’ cluster process in March 2023.

Months later, the UK government selected the Acorn Project in Scotland and Viking CCS in the Humber for track-2 funding.

Other CCS projects are in development throughout the UK, with many stemming from the North Sea Transition Authority’s (NSTA) first offshore carbon storage licensing round.

Powis said many of these additional projects are “waiting in the wings, ready to go”, with investors wanting to see a clear future trajectory for the development of the sector.

“To make sure that we’re on track to meet our 2030 targets we need to be capturing and storing 20 to 30 million tonnes [of CO2] by 2030,” she said.

“We’ve got to move forward with those first projects, but also the next ones in line that are ready to make sure that we’re on track to meet those targets.”

UK a ‘serious opportunity’ for CCS investors

Overall, Powis said the mood within the CCS sector is upbeat, with UK developers attracting attention from international investors.

“People are now looking at the UK as a serious opportunity for investing in CCS,” Powis said.

“We’ve developed business models, we’ve developed the regulatory and legislative framework to move this forward, and now we need to act and keep that pace.”

With major CCS projects taking shape in North Sea Denmark and Norway, as well as Iceland, Powis said the UK is not the only option for investors.

“These investors are looking at where to focus their efforts,” she said.

Offshore wind lessons for CCS

Powis said many CCS investors are multinational an will be making investment decisions “at a global level” in terms of which projects move forward.

She pointed to American supermajor ExxonMobil’s recent decision to back away from plans for a CCS pipeline as part of the Solent Cluster.

“[Exxon] couldn’t see a route to market at the moment in the UK, and so we need to make sure we don’t see others go that same way,” she said.

The UK should look to its experience in developing the offshore wind sector by putting place a framework for regular CCS allocation rounds, Powis added.

“Looking at what’s happened for offshore wind, it very much provides a signal to investors that there will be an opportunity this year and there will be a further opportunity in the next year, and they can start to plan towards that,” she said.

“I think that’s key in terms of having forward visibility of opportunity and scale of opportunity.”

As part of providing that forward visibility, the CCS industry wants clarity from Labour on the £960 million allocated to the green industries growth accelerator.

The government should also “learn the lessons” from offshore wind, Powis said, supporting the development of local content, supply chain capability and expertise in the CCS sector wherever possible.

Bringing in annual allocation rounds, similar to the Contracts for Difference scheme for renewables, would also provide greater certainty to investors, Powis added.

Carbon pricing and cross-border transport

Elsewhere, Powis said higher prices on carbon and the recent confirmation of a UK carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) will likely improve investor sentiment.

Addressing barriers to cross-border CO2 transport could also open up UK projects to emitters in countries like Germany which have limited options to store carbon domestically, potentially providing new revenue streams.

But with Denmark and Norway securing cross-border agreements with countries like Sweden, Belgium and the Netherlands, industry observers have warned the UK “risks wasting a naturally advantageous position” by not reaching similar deals.

“We have enormous CO2 storage potential in the UK, we’ve got one third of Europe’s potential geological storage which is much more than required for our domestic purposes,” Powis said.

“There’s an opportunity to open up a European wide CO2 storage market.

“There are some regulatory and legislative barriers there that we need to overcome to make sure that can become a reality.

“But also pushing forward with non-pipeline transport, including shipping, making sure that can move towards being operational… will do a lot to open up those markets.”

Without efforts to overcome these barriers, Powis said there is a “real risk” of the UK losing ground to Denmark and Norway.

Germany-based Scottish energy consultant David Scrimgeour echoed the concerns of the CCSA.

Speaking to Energy Voice, Scrimgeour said there is almost a “complete lack of awareness” of the UK’s offshore CCS potential among German industrial emitters.

With many firms in the world’s third largest economy looking to begin capturing their carbon emissions, Scrimgeour said UK projects should seek to capitalise on them.

With the Scottish government deepening its engagement with Germany on green hydrogen, Scrimgeour said there is an opportunity to build similar ties on CCS.

CCUS public perception challenges

With carbon intensive industries like steelmaking struggling in the UK, Powis said CCS offers a “very real pathway towards decarbonisation” for hard-to-abate sectors.

“Net zero is legislated… so each industry needs to know their route to decarbonisation,” she said.

But CCS technology has attracted scepticism globally over its feasibility, alongside criticism surrounding the high cost of projects.

The UK government strategy has also attracted criticism over for its focus on blue hydrogen and gas-focused CCS projects, amid warnings it could derail net zero targets.

In October, a group of UK climate scientists urged Labour to reconsider its CCS plans, calling for investment in areas like retrofitting homes and decarbonising transport.

Meanwhile, environmental groups have painted the industry as a “scam” promoted by Big Oil, creating a potential public relations problem for the sector.

Carbon capture and UK industry

But Powis said securing a viable CCS industry is not just a climate imperative for the UK, but an economic one as well.

“These other methods, they’re not going to address what CCS is addressing,” she said.

“They’re not going to address industrial emissions and as long as we still need those industries and those products from those industries, which we do, there is an alternative that we don’t develop and we don’t manufacture them here and we just import them, but then we’re importing all the CO2 and we also lose all the economic benefits if we don’t do that.

“[Investing in CCS] it’s never instead of those alternative decarbonization rates, it’s as well as.”

Powis said independent bodies including the Climate Change Committee, the IPCC and the International Energy Agency all recognise a future role for CCS.

“It’s not helpful to pit technologies against each other because they’re addressing different parts [of the problem],” she said.

“We can insulate every home in Britain, which we should have done… and should have been doing a long time ago, but that’s not going to solve the issue of industrial emissions.”

The CCSA estimates the UK could unlock between £20bn to £30bn in private sector investment by 2030 if the industry scales up to meet its targets.

Powis also highlighted that projects will not draw down government committed funding until they are operational, and if carbon prices rise that will limit the level of subsidy required.

Blue hydrogen

Similarly for blue hydrogen, which involves CCS when splitting natural gas to create hydrogen, Powis said the UK has to “use all the technologies available to us”.

Many UK CCS clusters involve blue hydrogen projects, including BP’s H2Teesside and Scotland’s Acorn project at St Fergus.

The industry sees blue hydrogen as an important transition fuel, enabling investment in hydrogen infrastructure while green hydrogen costs remain high.

” Green hydrogen will not be in a position to scale up to the levels that we will require for it to drive the hydrogen market in the immediate term, so we need blue hydrogen to kickstart the market,” Powis said.

UK carbon innovation

Establishing a viable CCS sector in the UK will also help foster innovation around new and emerging carbon-focused technologies, such as direct air capture (DAC).

Powis said historically the UK has been “very good” at homegrown innovation and research, but converting these into commercially viable and scalable solutions has proven challenging.

“We’ve got to make sure that there are opportunities to be able to do that, that the regulatory space is there and the investment space is there to facilitate that,” she said.

Swiss firm Neustark is one company investing in carbon removal innovation in the UK.

The firm recently launched its first site in the UK at Greenwich, where the company plans to capture CO2 from biomass sites before injecting it into recycled concrete for permanent storage.

Neustark chief executive and co-founder Valentin Gutknecht said the UK is an “ideal market” for the company because of its supportive policies surrounding CCS.

“The government is supportive of building a competitive carbon market and shifting the industry away from early-stage developments to a competitive commercial set-up,” he said.

“But there is not enough focus on carbon removal, or consideration of how carbon removal can be embedded into existing supply chains and industries beyond oil and gas rather than always requiring extensive new infrastructure.”

© Supplied by CCSA

© Supplied by CCSA © Supplied by Tanks arriving at No

© Supplied by Tanks arriving at No © Supplied by SSE Renewables

© Supplied by SSE Renewables © Supplied by INEOS

© Supplied by INEOS © Aerial Photography Solutions

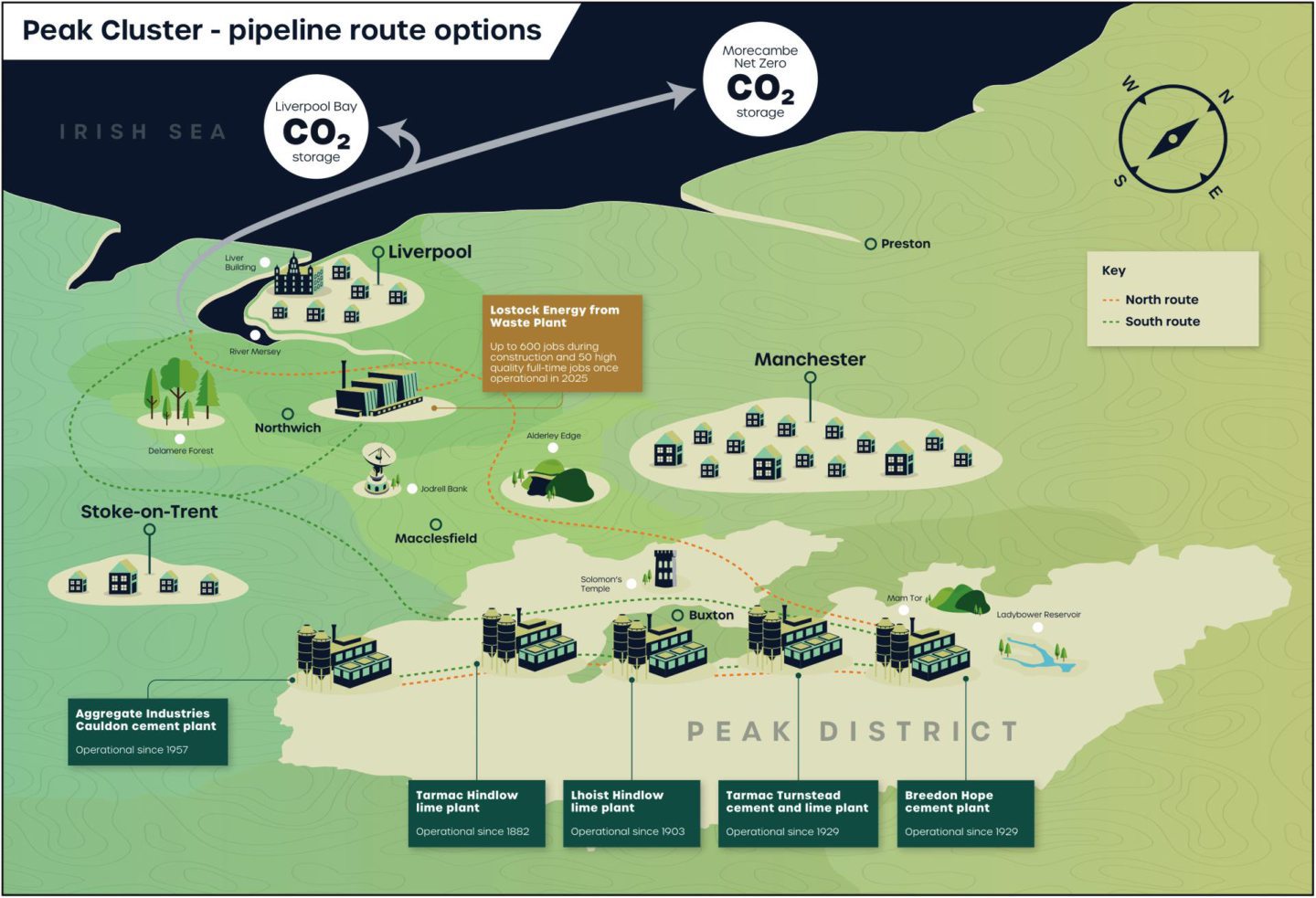

© Aerial Photography Solutions © Supplied by Peak Cluster

© Supplied by Peak Cluster © Supplied by Technip Energies

© Supplied by Technip Energies © Supplied by Neustark

© Supplied by Neustark