The idea that the UK’s energy market is ‘broken’ is both true and untrue at the same time. Long-standing warnings that the system of marginal pricing does not provide a meaningful value for energy security have been roundly proven right. High prices are the consequence.

That it does not put a price on pollution was equally evident, but eventually acted upon via the introduction of a carbon market.

Otherwise, it is working pretty much as intended.

In the UK’s wholesale gas and electricity markets, the highest bid that matches supply with demand sets the price for all. Gas-fired generation typically provides the marginal MW of power when demand is high because it can be dispatched flexibly, unlike wind or solar which depend on the weather – or nuclear generation, which aims to run at a steady rate, providing baseload rather than peak power.

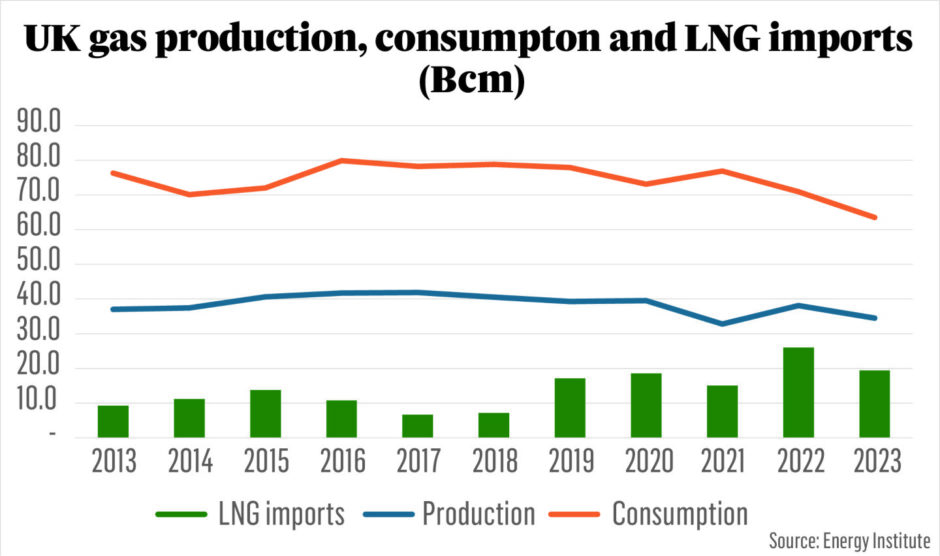

As gas-fired generation sets the marginal price of electricity, the price of gas becomes a key component of the electricity price. Despite still producing gas from the North Sea, the UK is dependent on gas imports, with LNG providing the marginal therm.

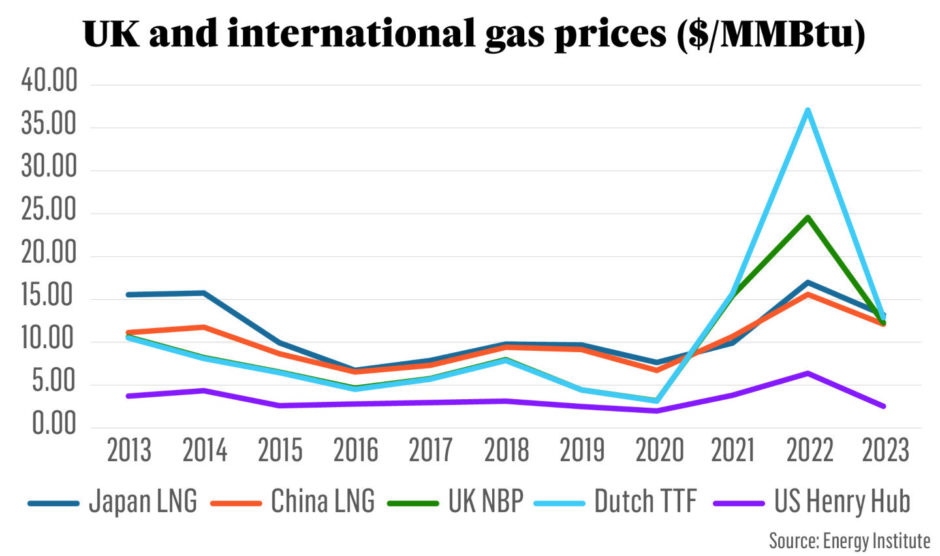

As in the electricity market, the marginal price sets the price for all. As a result, the international price of gas flows directly through into UK electricity prices. Forces far away that affect the supply and demand of LNG impact what UK consumers pay to run a fridge, watch the television or turn on the central heating.

The UK’s energy crisis is thus a product of its dependency on the international gas market and the forces to which it is subject. These, in recent years, have been momentous.

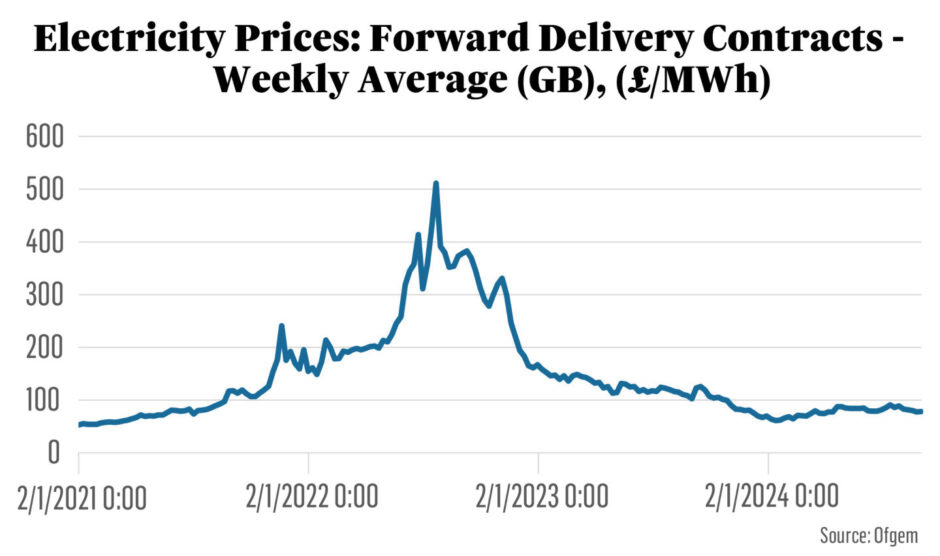

The energy crisis did not start with Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, but it certainly consolidated it; day-ahead electricity prices hit records in December 2021, two months before Russia invaded, but climbed to new highs thereafter as Russian gas pipeline exports to Europe were curtailed.

Almost all of Europe became increasingly dependent on an already tight LNG market, resulting in the massive peaks in both gas and power prices seen in August and December 2022. LNG supply takes time to increase and investment levels prior to the energy crisis were low, so there was little new capacity coming onstream to address the sudden surge in European LNG demand. Prices have still not returned to the levels prevalent before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

So what needs fixing?

The cost of a MWh of solar or wind power may be only £30, but the consumer might pay over £200, if that is what the price of gas and gas-fired generation dictates under a marginal pricing system. It does not seem fair, but the system is there for a reason.

High market prices provide a signal for investment. They encourage new generation capacity to be built. More capacity increases supply, usually of the lowest-cost forms of generation (as they promise the greatest profitability) and intensifies competition, ultimately reducing prices. In this sense, the marginal pricing system is not broken. It is doing precisely what was intended – providing a clear market signal for increased investment.

In the gas market, the same process is taking place. High prices stimulate investment and increased supply.

The problem is that building new generation capacity takes time, as does building new LNG capacity. Eventually… and none too soon for consumers and businesses – new wind and solar generation capacity will reduce the amount of time the UK electricity system is dependent on gas-fired generation and prices will fall.

Meanwhile, LNG prices by 2026/27 are also expected to drop as new liquefaction capacity comes online in the US, Qatar and to a lesser extent elsewhere.

The rebalancing of either or both of the electricity market (national) or gas market (international) will eventually return UK energy prices to more normal levels.

Interventions unsound

A key problem is that the marginal pricing system is reactive rather than anticipatory and the reaction takes time. It is at its worst when faced with sudden shocks, such as the loss of Russian pipeline gas to Europe. The more sudden the shock, the more brutal the adjustment period. The pressures on governments to come up with a ‘fix’ are intense.

Price caps and guarantees offer a degree of short-term relief to consumers, but retard market rebalancing by skewing the investment signals and investor confidence. If investors do not receive the returns dictated by marginal pricing, their enthusiasm to invest is diminished.

Moreover, some companies get caught in the middle – typically retailers. They face higher prices for the electricity they buy on the wholesale market, but cannot pass the cost through to consumers, whose prices are capped. The retailers go bust and competition in the retail market is damaged, usually benefitting large incumbent, vertically integrated suppliers.

On November 19, accountants Price Bailey reported that over half of the UK’s remaining domestic electricity and gas suppliers were technically insolvent and at risk of collapse.

Is there a fix?

Marginal pricing is beneficial in that it promotes the efficient allocation of resources, but only in the interests of maximising profits. It does not encourage the maintenance of spare capacity or large fuel stocks. Just as the marginal pricing system fails to price pollution, it fails to price adequately energy security. In this sense, marginal pricing didn’t break so much as never worked.

However, there is a fix – the energy transition.

Gas consumption will steadily be replaced by electricity and electrification, with gas-for-power generation out by 2035, the target for complete UK power sector decarbonisation. With no gas-fired generation, UK electricity prices will not be subject to the vagaries of the international gas market.

What then will set the marginal price, assuming back-up diesel generators are also regulated out of the equation on emissions grounds – curtailment, demand-side management, biomass-fired power plant? It is hard to say.

The marginal pricing system was designed for competing fossil fuels. Wind and solar add a new element of variable, must-run, zero fuel cost generation. The UK power system of the not-too-distant future will be dominated by must-run generators with no or relatively minor fuel costs.

Any surplus generation will be turned into renewable gases, stored or, in the worst-case scenario, wastefully curtailed. Meeting power demand will remain the priority and surplus generation implies prices trending towards zero in the wholesale market because the majority of generation will have no choice but to generate. The incidence of zero pricing in the UK wholesale electricity market, and across European markets, has been well documented.

The marginal price could be formed by the offtake of surplus generation for fuels and storage, both of which seek low prices. This would be an extraordinary turnaround: from being a product of fuel consumption, electricity becomes the raw material for the production of fuels. To keep fuel costs low (think of the high cost of hydrogen production), electricity would need to be cheap.

Market already changing

A market trending towards zero presents challenges for all forms of generation, as all need to recoup their costs. However, although they feed their generation into the wholesale market, much of the UK’s new generation capacity has already been removed from the marginal pricing system.

EDF’s two nuclear reactors under construction will be remunerated by expensive contracts for difference (CfDs). Most offshore wind is subject to CfDs, at more reasonable prices, as are increasingly solar and onshore wind via the UK’s renewable energy licensing rounds.

As these technologies begin to dominate, marginal pricing in the electricity wholesale market will make less and less sense, and its usefulness in providing a market signal for investment will fall, if not be lost entirely.

Moreover, the price paid by the government for the CfDs will increase as wholesale prices trend downward. Consumers would increasingly pay for electricity through general taxation. Prices would be heavily subject to new generation capacity construction via the government’s provision or withholding of new CfD contracts, a move, maybe inadvertent, in the direction of state planning with all the pitfalls that entails.

There is no reason why the marginal pricing system, designed for competing fossil fuels, should be fit for purpose in a world with no fossil fuels. But when and how it will be replaced are open questions.

Recommended for you