Offshore Energies UK (OEUK) has launched a new set of guidelines aimed at helping entrants into the offshore wind sector better understand the development process.

The guidelines are intended to address knowledge barriers to wind farm deployment, drive strategic supply chain investment, and speed up the UK’s transition to using homegrown renewable electricity.

OEUK wind energy manager Thibaut Cheret told Energy Voice: “It gives a clear pathway that helps companies prioritise their activities and know where their pinch points are going to be earlier in the game.”

Working alongside BVG Associates, an independent specialist renewable energy consultancy, OEUK outlined the procedures for establishing a wind farm, from first principals of leasing a sea area, to commercial market regulations and supply chain requirements:

Cheret warned that the complexity of the regulations covering offshore wind projects means that, even for seasoned players, not everyone in an organisation may understand the entire process.

“We put a full picture in one document, telling you how everything works and who is responsible for what,” he said.

“It’s to help people in the wind industry and people who are getting into it, especially the supply chain. Now, the supply chain has a tool to understand at what step projects are in and when they can start engaging with it.”

At present, supply chain companies have to play a guessing game to work out when and how to invest – with some of the larger tier ones having whole departments dedicated to predicting when certain projects will arrive at their key milestones.

“Wherever you play, you now have a signpost telling you what is important because there is potentially job activity for you.”

By signposting upcoming milestones, the supply chain can frontload, bringing forward work and making the right investments at the right time.

“This guide is also helping tier one and lower understand the process, so they invest at the right time. If you invest too early first, you probably buy the wrong things and end up losing money. If you’re too late, you risk missing the boat.

“For the UK supply chain, timing of the investment is critical.”

Guidelines

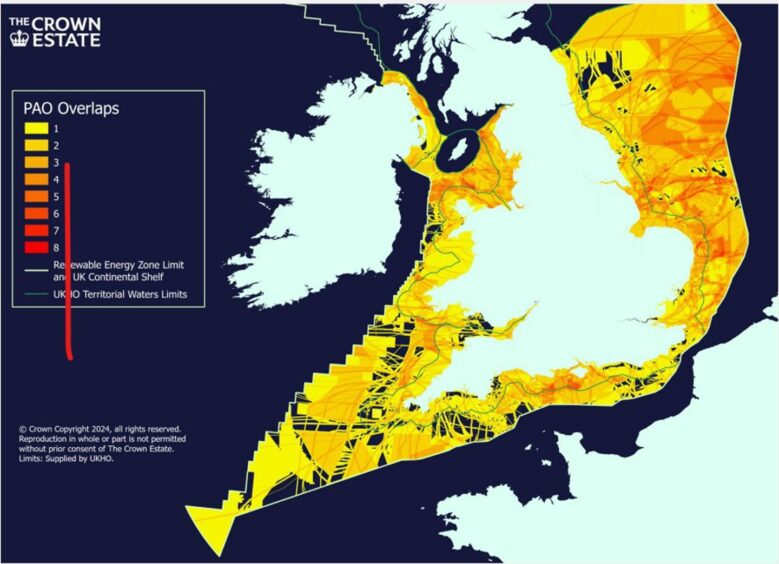

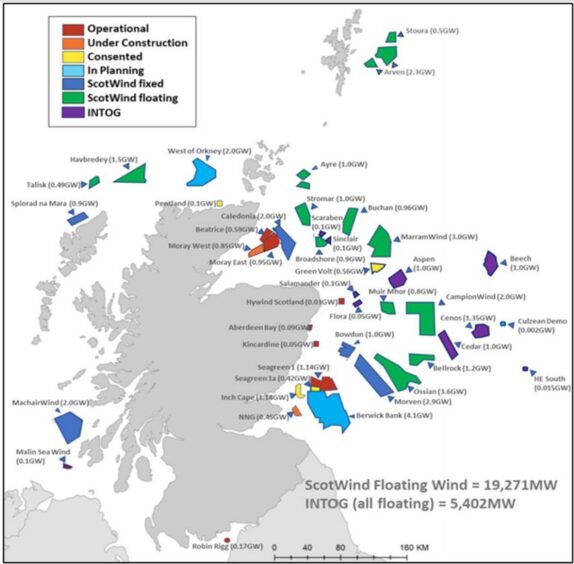

The guidelines include maps showing potential areas of opportunity for offshore wind farm development, the mechanisms of leasing agreements in different UK jurisdictions, consent, licensing, distribution, connections, and supply chain requirements.

This provides offshore wind farm operators and supply chain companies with a full picture of all the different agencies involved.

Part of OEUK’s aims for the offshore wind guidelines is to help companies progress through the approval process smoother and faster.

“Projects have a lot of costs due to delays,” Cheret noted. “It creates a lot of uncertainty and that uncertainty eventually increases costs.

“Eventually, the cost of delays will then reflect those costs in their contract for difference at auction. There is a high value to keep things flowing, as part of the price the consumer pays is due to inefficiency.

“If everybody has a common vision and identifies those pinch points early enough, they can be resolved before they cause delays.

In addition, the guidelines aim to help new players attracted by the UK’s booming offshore wind industry understand how the UK’s regulatory system works.

“ScotWind has attracted players who were working in different environments and markets that don’t have the same rules,” Cheret added.

The next steps

OEUK created its guidelines, in part, due to how complex it is to approve an offshore wind farm. Putting everything in one place was also intended to “hold a mirror to government,” Cheret said, to show how complicated the process is.

“Maybe part of the next phase of the conversation is how do we make this simpler,” he said. “By highlighting the complexity of a process, we’re also pointing to what could be improved.

“Now when we have the full picture, the dimension of the difficulty people face, we can take action.”

Compared to offshore wind, the oil and gas sector has a more condensed and streamlined approval process, with the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) acting as the main regulatory body.

“It’s well organised, you have a clear path that everybody understands. But for the wind industry, the regulation hasn’t reached the maturity of oil and gas and that’s why people are struggling,” Cheret added.

With multiple bodies, such as the Crown Estate and the Department of Energy and Net Zero (DESNZ), handling approvals for offshore wind, Cheret said that greater consolidation could help resolve some of these issues.

“GB Energy could play this role of coordinating with the other bodies. It doesn’t necessarily have to be one body, so long as everybody reads from the same playbook.”

Recommended for you

© Supplied by OEUK

© Supplied by OEUK © Supplied by Offshore Wind Scotla

© Supplied by Offshore Wind Scotla