Billions of pounds are required to provide the UK’s grid with its largest upgrade in history, turning it into a beast fit for a more electrified economy, running on largely variable generation sources many of which will be offshore. Can it be done?

An integrated national grid has been part of our lives since 1935. Unlike some elements of the energy transition, when it comes to transmission there is less need to reinvent the wheel – but the UK’s power grid was not designed for the generation sources that need to be built by 2030.

Wind and solar farms are widely distributed in relatively small units, or come in large remote units – for example, offshore wind farms. The transmission ‘supergrid’ built in the 1950s, by contrast, was based on the transmission of power from a core set of large fossil fuel generators in the centre of the country.

The Hornsea 4 offshore wind farm, approved in the sixth renewable energy licensing round, for example, will have capacity of 2.4 GW – comparable to two large nuclear reactors but located 69 km offshore. A large number of the UK’s wind farms, both in operation and planned, lie off the Scottish coast far from the UK’s main centres of power consumption.

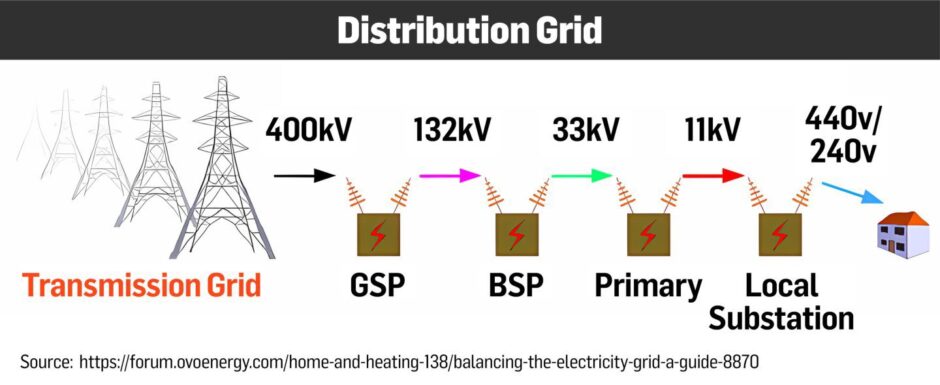

At the other end of the wires, some 1.39 million UK homes receive solar power, a number that will increase markedly based on the government’s targets. A system built for the one-way flow of electricity from large generators now has more than a million small generators at the distribution network level, feeding small amounts of electricity into the grid.

In simple terms, renewable energy generation is not in the places for which the current power transmission system was designed.

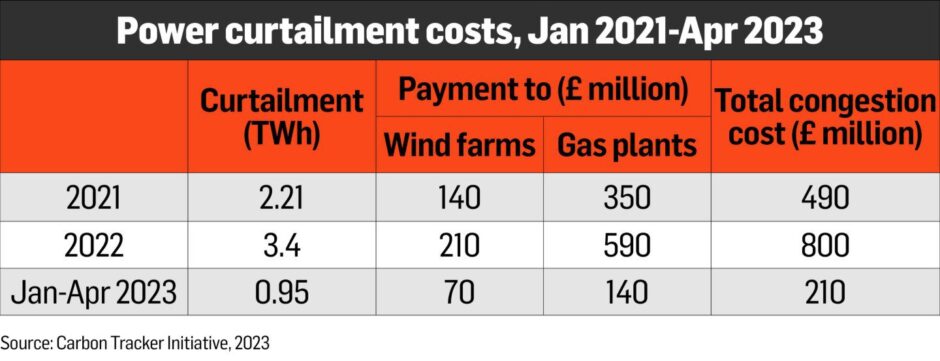

Major constraints already exist, for example at the Scottish-English border, resulting in the curtailment of green power, while others will emerge with the addition of more renewable energy capacity.

If the capacity targets for 2030 are met, but the transmission capacity is absent, the result will be more wastage in the form of power curtailment and an extended period of dependence on gas-fired power. The goal of a clean power system by 2030 will not be met.

Gone with the wind?, a report published by the Carbon Tracker Initiative in 2023 estimated that power curtailment could cost the UK £3.5 billion a year by 2030, and that wind generation in Scotland would grow four times faster than the construction of new transmission capacity.

Big plans, but late to the party

Congestion indicates that investment in renewable energy capacity has already outpaced grid investment and planning. This can be seen by the huge waiting list for grid connection, where many viable developments are blocked by ‘zombie’ projects that lack funding.

In January, the UK’s National Energy System Operator (NESO) blocked new projects from joining the mammoth queue. NESO says it imposed the pause to overhaul the application rules, but the risk remains that planned transmission investment will further lag generation in terms of delivery.

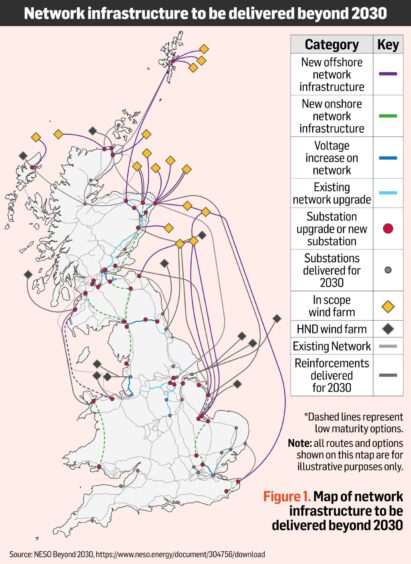

Integrating large amounts of offshore wind requires development of an offshore transmission grid and the reinforcement and expansion of both north-south and east-west transmission capacity.

National Grid Group plans up to £35 billion in investment in the UK’s transmission infrastructure between April 2026 and March 2031, including major projects, such as the Eastern Green Links 1, 2 and 3 and Sea Link, which will be some of the longest High Voltage Direct Current cables in the UK.

Overall, National Grid plans to invest £60 billion over the next five years, nearly double its investments in the prior five years.

Construction time challenges

These large projects will take time to plan and build, although a focus on offshore transmission should reduce the consenting complexity of many projects, owing to the lower level of community impact. The challenges revolve not so much around technical feasibility or expertise, but permitting and supply chain capacity and coordination.

Currently, it takes about 12-14 years to build a new transmission line in the UK. In a 2023 study, Electricity Networks Commissioner Nick Winser concluded that planning and construction times could be reduced to seven years, much more than the three-year reduction remit he was given.

However, doing so would require full implementation of 18 recommendations, starting with a clear definition of the roles and responsibilities of key parties to the process such as the government, the regulator Ofgem, transmission owners and the Future System Operator.

While many steps have been and are being taken to streamline processes, doing so remains a work in progress. Winser’s seven-year timeframe is a best-case scenario, in which all recommendations are speedily implemented and work, yet it still falls short of the 2030 target.

Moreover, the UK’s transmission system operators plan to build multiple new transmission lines simultaneously. Such an endeavour will stretch supply chain and staffing capabilities, as well as making a huge call on permitting and regulatory bodies.

NESO’s warning that total power sector decarbonisation by 2030 will require simultaneous delivery of different key elements of the UK’s energy system is highly pertinent. The generation capacity targets are undoubtably a stretch, but delivering the transmission requirements on time appears even harder.

In the third part of our series, Metamorphosis – value shifts in the UK’s emergent clean power system, Energy Voice looks at the operability of what will be a very different power system from today.

The system will run predominantly on variable rather than dispatchable generation, while users will be consuming more electricity and generating more of their own. How will it all work?

Recommended for you