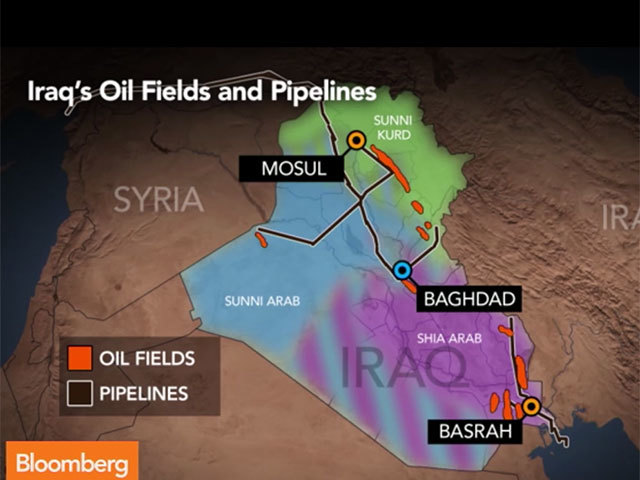

As modern Iraq collapses, the northern region of Kurdistan is emerging as an oasis of relative calm — with plenty of oil to support its political ambitions for independence.

With the advance of Islamist rebels deep into Iraq, autonomous Kurdistan is increasingly rejecting Baghdad’s claims over its oil. Last week Kurdish leader Massoud Barzani seized control of fields near Kirkuk, in the latest move by Kurdistan to assert control over the region’s oil.

“Kurdistan has resources and it’s well organised,” said Brian Gallagher, an oil analyst at Investec Plc in London, who follows several explorers working in the region. “The Kurds are probably winners out of the recent events long-term.”

And the same holds true for the oil companies that have invested there. Since the US invasion of Iraq more than a decade ago, western drillers have beaten a path to Kurdistan, a mountainous region that’s been less explored than the oil heartlands in the country’s southern deserts. First came small companies willing to take a gamble, then giants like Exxon Mobil Corp. and Chevron Corp. followed. Kurdistan now hosts more than 20 foreign companies exploring for oil and gas, according to the regional government’s website.

The region has enormous oil-production potential. The Kurdish government estimates untapped resources may total 45 billion barrels, more than all remaining reserves in the US And output is increasing quickly after a pipeline linking Kurdistan directly with Turkey opened in May.

“The question is not how much oil and gas Kurdistan has, but how to monetise the enormous oil and gas reserves, which remain trapped in this land-locked region,” Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. wrote in a report this month. “The barriers to development are not physical, but geopolitical.”

Barzani’s administration, which has promised a vote on independence from the rest of Iraq, says output may jump from 400,000 barrels a day in 2014 to 1 million barrels a day next year, and twice that much by 2019.

Explorers in Kurdistan haven’t faced the same risks as those drilling in the more volatile south of the country. The region is protected by the Peshmerga, a well-armed military force that emerged from Kurdish resistance to Saddam Hussein’s regime, limiting the bombings and sectarian violence that have scarred other parts of Iraq since the US invasion.

As Islamist militants grabbed control of large swathes of the country from Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki’s government in Baghdad over the past two months, the Peshmerga has defended Kurdistan’s borders and asserted control of disputed areas. On July 11, they took control of the Kirkuk and Bai Hassan oil fields from Iraq’s state-run North Oil Co., the Kurdish government said.

A Kurdish government official didn’t respond to e-mail and phone requests for comment.

“As of today Kurdistan remains a safe place to operate and we have maintained all our activities,” Emmanuel de Guillebon, a managing director for Total SA in Iraq, said in a phone interview. Total, France’s largest oil company, plans to drill at least two wells at its operated blocks in Kurdistan through next year and is appraising local fields with partners Marathon Oil Corp. and Oil Search Ltd., de Guillebon said.

Mol Nyrt., a Budapest-based oil explorer that’s been working in Kurdistan since 2007, said it’s confident enough to have opened a headquarters for its Middle East and Africa operations in the Kurdish capital, Erbil.

“We don’t expect any changes in our operations and in our fruitful relationship with Kurdistan regional government,” said Szabolcs Ferencz, Mol’s senior vice president for corporate affairs. “Kurdistan already enjoys significant autonomy within Iraq and has its own security forces, police and ministries.”

While the region has enjoyed a large degree of autonomy, the federal government in Baghdad, responsible under the Iraqi constitution for managing oil shipments and revenues, had blocked Kurdistan from exporting oil on its own.

Barzani’s administration broke that arrangement when the pipeline to Turkey started flowing in May, loading a tanker at the Turkish port of Ceyhan on the Mediterranean and banking the cash. While the central Iraqi government disputed the legality of that sale, exports are continuing and more ships have loaded Kurdish oil. In a judgment last month, the Iraqi supreme court denied a request by the Baghdad government to prevent Kurdistan from exporting oil directly.

Genel Energy Plc, a London-based company headed by former BP Chief Executive Officer Tony Hayward and the biggest oil producer in the region, saw its output jump by about a third in June to 84,000 barrels a day because of the new pipeline. It supplements crude loaded onto trucks and consumed locally or shipped across the Turkish border by road.

“The Kurdish Regional Government has sold the first cargo of oil exported through the pipeline,” Genel said in a statement. “We expect this process to bed down and to see oil continuing to flow through the pipeline, tankers being loaded and money received.”

The Kurdish government escalated its dispute with Baghdad this week, issuing a legal notice saying under current circumstances the Iraqi constitution gave it the right to manage its own crude sales. That’s because the federal government has failed to distribute oil revenue in the proportions agreed.

The story of Exxon in Iraq since the US invasion in 2003 shows the the growing strength of Kurdistan versus the rest of the country. In 2011, Exxon switched the focus of its Iraq operations from contracts to renovate giant fields in the south to exploring for new deposits in Kurdistan, a move that angered al-Maliki’s government. The Irving, Texas-based company said in May drilling operations are under way in two blocks in the region.

Kurdistan “will be a bit more stable than the south and has the ability to monetize its own resources base,” said Sanjeev Bahl, an analyst at Numis Securities Ltd. in London. Oil companies working there “will reap rewards,” he said.

Recommended for you