Ground-breaking research to measure offshore workers’ body size and shape with 3D scanners and which was started in 2012 is nearing completion.

The result of measuring in detail 600 offshore workers who regularly commute offshore will be published soon.

Provisional findings are encouraging, according to Les Linklater, team leader at UK offshore safety initiative Step Change in Safety.

The dataset will enable our offshore industry and helicopter operators to establish a sensible way of ensuring that workers are allocated the correct seats for safety reasons when shuttling.

Crucially, it will enable the industry to meet a critical safety deadline set by the Civil Aviation Authority for April next year.

It appears too that the sensitivities around fat people have been sidestepped by devising a way of assessing the size and shape of workers based on musculo-skeletal information; in particular, breadth across the shoulders and depth of thorax (chest).

According to Linklater, it is already clear that most offshore workers need not worry about their size and shape, with nearly all fitting into two size categories . . . regular and what may come to be described as “extra broad”.

Simplistically, this practical . . . and non-embarrassing . . . approach means that the key measurements of everyone who flies offshore regularly (about 26,000) or fairly often (around 16,000) will be recorded on their Vantage POB passports and can be used to enable passengers to be put in seats that best match their characteristics, bearing in mind that window sizes may vary too.

Linklater affirmed that the industry should have little difficulty in meeting new passenger size and shape requirements of the Civil Aviation Authority.

But it is important to note that the RGU work pre-dates the CAA inquiry into North Sea helicopter safety which led to a set of stiff demands set out in the CAP 1145 report published early year.

The UK offshore industry had been planning improvements to safety standards and equipment for offshore workers for some while and is a core reason as to why the Robert Gordon University work was commissioned.

It is being led by researchers at RGU’s Institute of Health and Wellbeing Research (IHWR) in collaboration with experts from Oil & Gas UK. Leaders Dr Arthur Stewart, knowledge exchange co-ordinator for IHWR, and Dr Graham Furnace, medical advisor for OGUK conceived the project in 2011.

Linklater told Energy: “The dataset is there. What we’re now doing is putting it through modelling to enable us to understand what the norms are; what the distribution curve is; and how that may or may not have changed over time (last dataset was gathered in the 1980s).

“That gives us the best opportunity to say, this is what the sizes of our people are. But bear in mind, this was started long before the CAA CAP 1145 report.

“This was about how we as an industry have to design future platforms and their safety systems including rapid egress, lifeboats and for confined spaces.

“There’s a lot of data that we hope will be very useful for the CAA regarding the need for people to be compatible with the window they’re sitting next to.

“It’s fundamentally an ergonomics issue . . . making sure that we know that, if you are sitting next to an exit, you can get out through it. So, we’re tapping into that data to help us accomplish that task, so to speak.”

The Step Change HSSG’s (Helicopter Safety Steering Group) passenger size workgroup is already implementing measures based on preliminary interpretation of the RGU data.

The first thing that the group has just done is define a clothing policy, that is, what workers should wear under their survival suits. That may seem not that important. But wearing the right clothes changes your volume, also comfort and ability to move easily.

That policy came into effect on October 1, which is when winter starts for UK offshore workers in terms of sea temperatures.

“That’s the first basic deliverable,” said Linklater. “It’s about here’s what you should wear in the summer months and here’s what you should wear in the winter months. It’s about survivability in the unlikely event that there is a (further) helicopter in the water.”

But the big one is correctly matching passengers to the ergonomics of the machine they’re commuting in to help maximise their chances of survival should an aircraft ditch.

Linklater: “What we have to date is a very simple set of measurements . . . criteria that we’re going to use.

“Through the analysis that we’ve done, neither weight nor BMI (body mass index) are good for coming up with the right answer in terms of compatibility with exits.

“Using musculo-skeletal information . . . frame size . . . is a much more effective indicator. Our bone structure doesn’t tend to change, although we can add muscle and other compressible tissue, notably fat.

“Weight and body mass do not give us that clear sense of how big somebody is. But skeletal structure does.

“Using shoulder measurement gives you a fixed point; another dimension that we’re looking at is a thorax depth measurement.

“So, if we’re this deep and this wide, we should be able to fit through a window of such and such a size. Of course, compatibility and achievement are two different things.

“In understanding this, it gives us some basic categories that we can begin to apply. We will be putting people into specific categories once final measurements are defined.

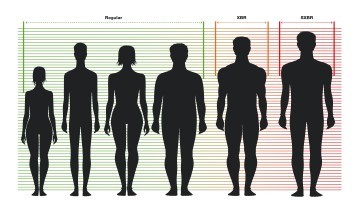

“There will be a standards category for regular people who can fit through any window in any aircraft.

“Then we will have what will probably be described as extra-broad (XBR – 22 inches or more across shoulders).

“That extra broad category means that you will have to sit in a seat near an exit compatible with your size.”

Because the North Sea industry uses a diverse helicopter fleet with different window sizes and different seat configurations, the CAA believes about 30% of overall seating capacity will be suitable for XBR.

StepChange is still determining the break-point for super-XBR.

An underlying code of practice will be established to enable people to be correctly seated.

When people check in there will be a process of measurement; this will be flagged through Vantage. This will not be insensitive; Linklater is clear that people must not be handled like baggage.

He is also confident that “at this time we don’t think there are any people who might fit into the ‘too big’ category. It’s not that we don’t have big people; because we have big, strong people in this industry,” said Linklater. “We also have some aircraft with very big windows. And therefore it looks for the most part that we will be able to manage this.

“The level of management will get to quite a high level of detail in terms of logistics. That will be one of the real challenges . . . a pinch point for us as an industry.”

So how will the logistics of allocating people simply be managed; making sure they are in the right seats?

Will it be semi self-sorting; after all, this is an intelligent workforce?

“There is no doubt that, as an industry, we have the capacity and capability to manage this,” replied Linklater. “But I do think we have to recognise that, the minute we start classifying people as extra-broad, we have to be sensitive to what that means.

“We have to find ways of ensuring that, if you’re on a helideck, late on a winter’s day in poor light, helideck attendants can easily identify who they are and what seats they must sit in.

So we have to think about human factors issues, to make sure that if you’re sitting in a helicopter seat, that the nearest exit is compatible.”

While taking the musculo-skeletal route for assessing offshore commuters appears to be the fairest way forward, nonetheless weight and lifestyle are issues for the North Sea industry and Linklater is frank about that.

“In coming up with an answer to make sure you’re compatible with a window size does not mean that we as an industry should not be addressing health and well-being issues,” he said.

“I’m 25 years older than when I first went offshore; I’m a different size; I have a different fitness level than when I first went offshore. I have to take some responsibility for myself and manage that.

“But this weight thing … this is not an offshore issue, it’s a societal issue. We need to continue to engage in that process of how do we set people up to succeed in the offshore environment and health and well-being is equally important as all the other things that we do.”

The CAA is fully au fait with the RGU work and wider discussion as it is a member of the psssenger size working group, as are the other stakeholders, including workforce representation.

“All the key players are at the table, trying to come up with the right answer; or the very best possible answer. That’s important,” said Linklater.

“Recognising that the date for this to come into effect is April 2015, we really need to be working this and having the very best solution during October and sharing this with the industry, so that people know how we’re going to manage it, this is the engagement model for your staff, this is what you can do about it as an individual.”

One thing that won’t happen is that windows in the existing fleet of aircraft are made larger. Structurally that is simply not possible. But it doesn’t mean that manufacturers have been doing nothing about better ergonomics … better safety.

“We’re seeing that coming in with the likes of the Airbus Helicopters EC175. That is an aircraft that has been designed specifically for offshore service,” said Linklater. “It has larger windows, we have it now.

“But because window-frames and so-forth are part of the structure of existing aircraft, re-engineering is pretty much impossible.

“For the regulators and airframe manufacturers, it is important for them to know where the offshore industry is going … the kinds of challenges that it faces, including personnel comfort and safety.

“We’ve seen that in HSSG where both Airbus and Sikorsky are at the table and engaging and beginning to use the operational intelligence coming straight from the workforce, almost in real time. The helicopter manufacturer is now in the room, speaking to the passenger. That has to be a good thing.

“However, helicopters take a long time to design, longer time to certify and then to manufacture. So it will be a number of years before we see some of these things in reality.

“As an industry we have to find sensitive, sensible and practical ways of managing the safety challenge.

“We’ve spent a lot of time trying to find that in this case, because of its complexity and attached emotion, whilst trying to find the best safety outcome is hugely important.

“This is not about compliance or regulation. This is a people-centric issue; which means its complex. Caring about achieving the right solution is why we’re taking our time, why we’re making sure that, fundamentally, we can as an industry live with and deliver practical outcomes.”

Recommended for you