For a country whose economy relies mainly on tourism and tea, the discovery of oil is one of the most exciting things to happen in development terms in the history of this East African nation.

The ability of a sub-Saharan country to be self-sufficient in energy has the potential to become an engine for economic development beyond anything seen in the area over the last 100 years. Clearly there are challenges, both to the extraction and the geopolitical sensitivity of the find. Kenya’s Lokichar Basin lies on the border with South Sudan, and it was its neighbour’s oil reserves that drove the civil war and recent independence of the South Sudan state from its mother country.

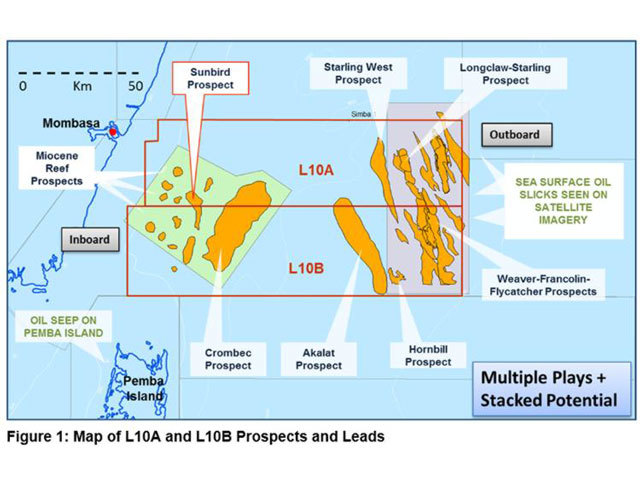

Clearly there are security risks, with this part of the coastline being party to raids from Somali pirates and terrorist cells – not to mention the potential for unrest in neighbouring countries, as they eye up such a large natural resource. This year, oil was also discovered offshore from Kenya – again causing security concerns, with similar risks from marauding Somali pirates.

There is still a great deal of work to be done, with much uncertainty around fiscal, political and security concerns. However, Kenya has shown that it is capable of crafting a vision and has already moved beyond simple rhetoric. It has recognised the need for a skilled workforce to support this new industry and is encouraging a home-grown approach – unlike other African countries, which support foreign universities. It has also enforced the training of locals by oil companies operating in the country. This could be extended to encourage a local service-based economy, providing much-needed employment in areas such as logistics, maintenance and eventually for technology-based services. Kenya’s National Oil Corporation (NOCK) is planning to set up the region’s first seismic data processing centre by 2015. This is evidence of long-term thinking, often lacking in more developed nations.

Following the granting of development rights to oil companies and a $50m loan by the World Bank, we are now witnessing an old-style oil boom in Kenya. Concerns are raging as to how Kenya should use this newly discovered resource responsibly. Past experiences in West Africa have shown how oil has the ability to corrupt a country and its economy.

Kenya’s leaders must decide whether or not they want Kenya to become a role model for other states or stick with a well-trodden model favoured by other African oil-producing nations. In Kenya, 38% of the population lives in absolute poverty, with only 18% having access to electricity. Kenya’s leaders will be able to improve living standards and invest in areas such as health and education.

Potential investors will need to weigh up the risks and challenges if capital is to continue flowing into the country’s cash-hungry petro-economy. Sending clear signals to the investor community suggesting Kenya is serious about creating the right environment could go a long way to mitigating those risks and allaying concerns. Creating such an environment must balance the tension between the desire to attract investment and the need to ensure that the wealth created by oil is used responsibly.

This newfound wealth is starting to force policy-makers to address the political instability in the area and, with enough oil to pay for investments in security, we should start to see improvements.

I am confident that Kenya will break the mould and do the right thing for its people. After all, the decisions it takes will have far-reaching and lasting consequences for both a nation and a continent.

David Delvin is the vice president of Hitachi Consulting.

Recommended for you