The promise of plentiful jobs and salaries as high as a quarter-million dollars a year lured Colombia native Clara Correa Zappa and her British husband to Perth, Australia, at the height of the continent’s oil and gas frenzy.

Engineers were in high demand in 2012, when oil prices exceeded $100 a barrel, making the move across the world a no- brainer. Within two years, though, oil plunged to less than half the 2012 price and Zappa lost her job as a safety analyst. Now she’s worried her husband, who also works in the commodities industry, could also lose his job.

Such anxieties are rising at a time when the number of energy jobs cut globally have climbed well above 100,000 as once-bustling oil hubs in Scotland, Australia and Brazil, among other countries, empty out, according to Swift Worldwide Resources, a staffing firm with offices across the world.

“It’s shocking,” Zappa, 29, said in a telephone interview. There is “so much pressure for him to keep his job and even work extra.”

Her concerns mirror those of tens of thousands of workers who migrated to oil and gas boomtowns worldwide in the years of $100-a-barrel crude, according to Tobias Read, Swift’s chief executive officer. While much of the focus on layoffs has centered on the U.S., where the shale fields that created the glut have seen the steepest cutbacks, workers in oil-related businesses across the globe are suffering, he said.

Job Insecurity

“The issue is one of uncertainty, of whether there’s a job out there,” Read said in a phone interview. “For seven years, there was a shortage of staff. Now for the first time, there’s a surplus. Currently almost no one is hiring.”

One by one, engineer Dipankar Das has heard from friends across the industry as layoffs rolled out across Australia. A friend at one company was asked to take a year of unpaid leave. Many are moving, which is what Das said in an interview he plans to do.

“You get all these skills, all these projects that have been completed over the years, and then all of a sudden it’s over,” said Das, a native of India who has worked in Australia for seven years. “It’s disappointing, but what can you do?”

The outlook isn’t brightening. After briefly rising above $50 this month, U.S. crude fell again Wednesday to settle at $48.84 a barrel. Citigroup Inc. said oil could drop to “the $20 range” by April as oversupplies build.

Further Tightening

How long it will take for the job carnage to stop is now the main question confronting industry workers. Executives at companies including BP Plc and Royal Dutch Shell Plc have announced spending cuts of more than $40 billion and assured investors they’re ready to tighten further if the market doesn’t recover significantly.

Australia stands out as especially hard hit, with a labor force already decimated by a slowdown in the coal mining industry.

Energy companies including BG Group Plc and Woodside Petroleum Ltd., which are spending $70 billion to build natural gas export plants in Australia, are seeing those projects delayed, postponed or winding down, leaving workers with nowhere to go after losing their jobs.

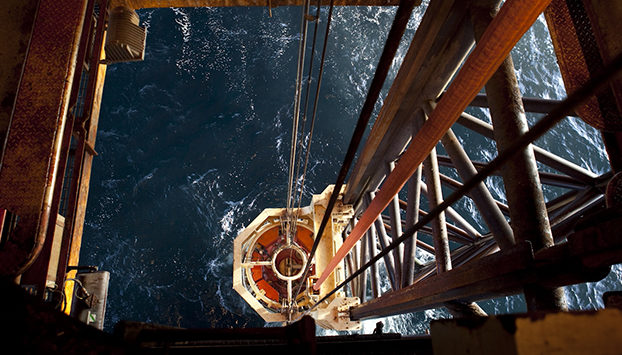

In Brazil, a graft scandal that led to the resignation of the CEO of state-run Petroleo Brasileiro SA on Feb. 4 has deepened the crisis surrounding oil. Brazil’s bounty lies offshore in the Campos basin, a formation rich in hydrocarbons nestled beneath vast layers of salt that make drilling expensive and risky.

Recovery Uncertain

The cloud over Brazil’s industry is halting development projects in Macae, a city of 230,000 about 115 miles (186 kilometers) northeast of Rio de Janeiro. International schools have closed as workers were sent to other regions, and oil royalties to the city this year may be cut in half, said Joao Manuel Alvitos, the city’s planning secretary.

“The scenario is extremely unfavorable,” he said. “We’re hoping for a recovery in the long term, but I don’t believe that the industry is going to recover quickly.”

Mexico’s oil prospects also are grim. In late 2013, the country began taking steps to revise its constitution and end a seven-decade monopoly, anticipating billions in investment from the world’s biggest oil companies.

Petroleos Mexicanos, which employs 153,000 workers and has promised to protect them amid the oil rout, began slashing contracts and purchases this year in a bid to save $2 billion to $3 billion. That plan has left as many as 8,000 workers, many concentrated in the port city of Ciudad del Carmen, without work, said Gonzalo Hernandez, head of the city’s Economic Development Chamber in Campeche state.

Dashed Hopes

Many workers who thought ending the monopoly would mean more jobs feel betrayed.

“The energy reform is a lie,” said Daniel Aquino, a drill rig welder who was waiting for work alongside hundreds of others late last month after the Pemex cuts were made public.

Around the North Sea, where drilling is serviced largely from Aberdeen, Scotland and Stavanger, Norway, job cuts now exceed 11,500, according to DNB Markets and Unite, the U.K.’s largest labor union. As many as 30,000 more may disappear, according to Menon Business Economics AS. BP wrote down the value of its North Sea operations by $3.6 billion, and CEO Bob Dudley on Feb. 3 gave dire warnings about the region’s future.

Late last year, Aleksander Gumos knew many people who were losing their jobs in Norway as the market crash worsened. Still, he just thought he’d have to work more hours to make up for those who were let go. Instead, he was added to the list of unemployed in December.

Gumos, a Polish citizen who relocated to Norway and bought a house in 2009, is trying to be flexible. He’s had several interviews with potential employers, including in the industry and academia.

“I thought I was doing my job well, at least judging by my record, feedback from clients, not least on projects,” said Gumos, who worked for Subsea 7 SA in data processing. “It was very surprising. I almost couldn’t believe it.”

Recommended for you