Subsea equipment specialist Ashtead Technology has been supporting attempts to explore the wreckage of the United States Navy’s last flying airship, which crashed in 1935.

The Aberdeen-based firm, which usually works with oil and gas sector companies, provided subsea inspection equipment to study the wreckage of the USS Macon and carry out an in-depth corrosion analysis on the aircraft to monitor deterioration, 1,400 below the surface of the Pacific Ocean.

It supplied its Polatrak Deep C Meter 3000, which allowed researchers to measure the gradual corrosion of the aluminium materials and sample the conditions for metallurgical study.

The Macon served as a flying aircraft carrier, designed to carry biplane aircraft that would launch from its underside.

Designed for long-range scouting, it crashed off the coast of California when it was returning to the Moffett Federal Airfield following a successful exercise over the Channel Islands, Southern California.

A storm caused extensive damage to the airship, control was lost and the USS Macon sank.

Two crew members died and the crash ended the Navy’s quest to use airships as long-range scouts for the fleet.

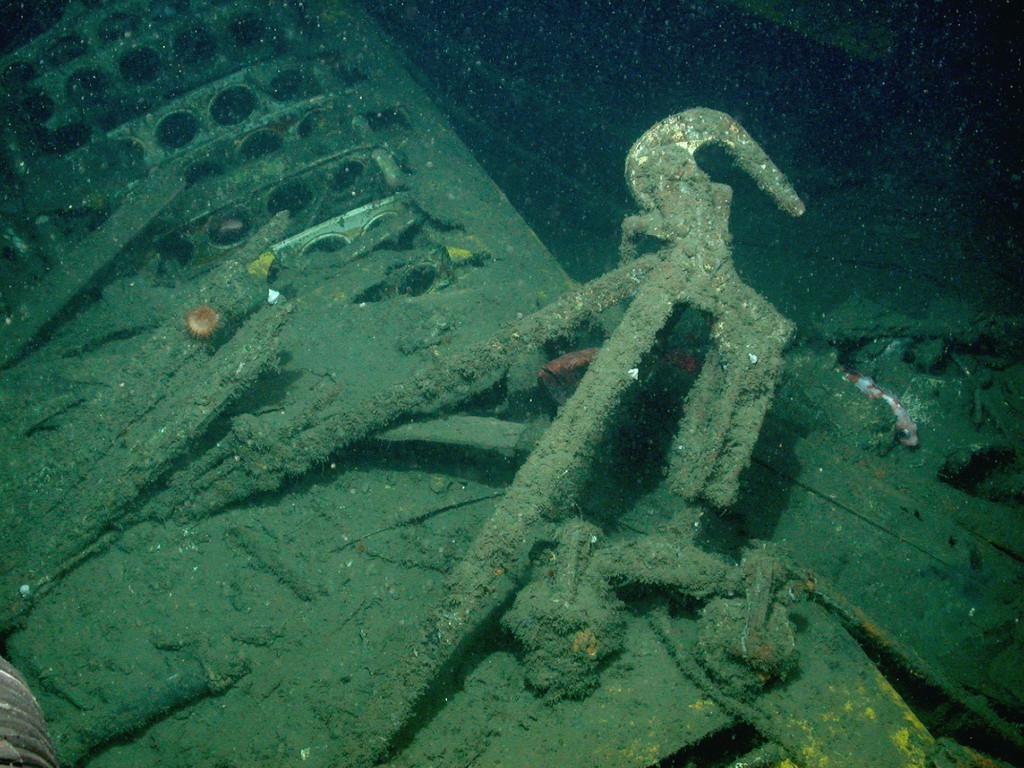

The recent expedition was led by archaeologists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Naval History and Heritage Command’s Underwater Archaeology Branch, and Ocean Exploration Trust to piece together a clearer map of the wreck site and to study how the remains of the airship were being consumed by the sea.

Ashtead vice president Chris Echols, said: “It’s been an honour to help answer some of the questions that have surrounded the tragedy and have been able to build up an accurate picture of the USS Macon and its current state.

“Earlier explorations of the site in 1991 and 2006 photographed and identified the engines, fuel tanks, ovens, tires, and the four biplanes, all of which were still relatively intact, however with new advances in technology, we can help researchers delve deeper and gather more meaningful data from the site.

“They were able to gain a better understanding of how long the wreckage will remain intact and document exactly what they encountered at the bottom of the ocean.”

The exploration team used Ashtead’s Polatrak Deep C Meter alongside the Ocean Exploration Trust’s Nautilus ROV to take a 360-degree video of the site, assess corrosion and measure how much sediment had built up since 1935.

The 12-hour expedition, which was broadcast live online, revealed the wreckage is corroding faster than expected.

“The aim of the mission was to monitor and preserve the wreck site to the best of our ability.

“The wreckage will continue to deteriorate, but we want to continue to document its condition now and into the future.

“We’re really extending the life of the airship and documenting the past 80 years she spent under water, where the majority of her life has been spent,” said NOAA archaeologist Megan Lickliter-Mundon.

“We already had a good understanding of how materials from older shipwrecks – wood, iron, copper alloys – react to their underwater environment.

“However, with 20th Century materials like aluminium alloys, we still haven’t quite figured out as a discipline how to best conserve the material, or how those materials react with their environment and with other materials.

“This was an opportunity to learn through the samples that we collected about the rate of corrosion and how to best help preserve them going forward.

“There are great environmental challenges associated at 1,400ft below the sea surface and without the help from Ashtead, we wouldn’t have been able to preserve and document artefacts for future generations.”