Given a choice, Statoil ASA and the other owners of the giant Johan Sverdrup oilfield would have preferred to avoid the collapse of crude prices that has upended the industry.

But there’s a silver lining: price cuts by desperate oil service companies are now raising margins on projects that are still viable as crude prices have slumped below $30 a barrel.

For Sverdrup, which may hold as much as 3 billion barrels, the crash could help make it among Norway’s most profitable projects ever. But there’s a catch: crude prices will need to recover by the time production starts in 2019.

“The Johan Sverdrup project will be an all-time profitable project because it’s being developed now with very low input prices,” said Jarand Rystad, managing partner at Oslo-based consultancy Rystad Energy AS. “The oil price will rise, so it will be an enormously profitable field.”

Statoil, the operator of the field, has cut the estimate for capital spending on Sverdrup to 160 billion kroner to 190 billion kroner from 170 billion kroner to 220 billion kroner previously, Det Norske Oljeselskap ASA, another of the deposit’s stakeholders, said Monday. With 60 percent of the investments in kroner, the project is also profiting from a slide of the Norwegian currency against the dollar in parallel with the oil slump.

Det Norske expects the investments to come in at the lower end of the range, and maybe even lower, Chief Executive Officer Karl Johnny Hersvik said.

“You’re hitting a market in steep decline, and there’s good capacity to implement this type of project in the Norwegian supplier industry, at very advantageous prices,” he said. “So at least the first part of the equation is fulfilled.”

According to Rystad, the return on invested capital in the field will be 25 percent if their forecast of oil returning to $100 in 2020 comes true.

Statoil agrees that the timing is good with project costs in general dropping as much as 30 percent to 40 percent, according to Ola Anders Skauby. The company has so far awarded contracts on Sverdrup for more than 50 billion kroner, of which over 70 percent has gone to Norwegian companies such as Kvaerner ASA and Aker Solutions ASA.

“Norwegian suppliers have proven very competitive,” Skauby said by phone. “That’s led us to already see a positive development for Sverdrup. We’ll have to get back to possible updates on figures.”

Statoil and Det Norske expect the second part of the equation to add up as well, with oil prices rising in the long term. The benchmark Brent blend will average $63.5 a barrel in 2019, according to the mean estimate of eight analysts surveyed by Bloomberg over the past two months.

“Sverdrup is perfectly timed in relation with the oil price drop,” Teodor Sveen Nilsen, an analyst at Swedbank AB, said by phone. The field will end up in the top five most profitable oil projects offshore Norway along with Statfjord, Oseberg, Ekofisk and Gullfaks, if not ahead of these, he said.

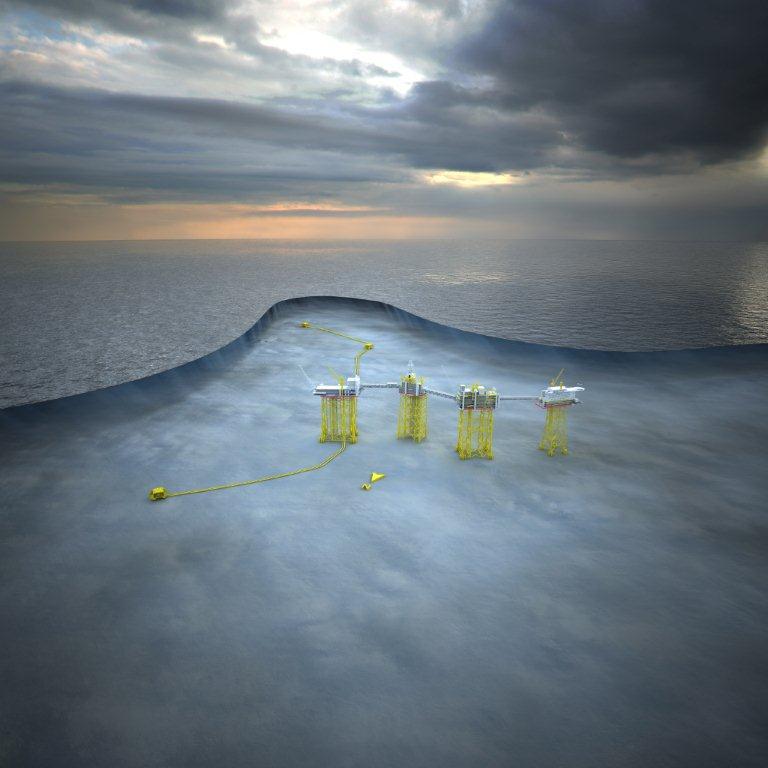

Statoil started awarding a flurry of contracts to suppliers from engineering firms to platform and pipeline builders after submitting a development plan to the government last February. A couple of examples illustrate how costs have fallen: rig owner Odfjell Drilling agreed to drill starting this year for half the price it charged before; Kvaerner, which will deliver one platform deck and three substructures, signed contracts for the latter last year at the same nominal price as it was charging in 2005, it said in October.

The project now has a break-even price of $25 a barrel, according to Swedbank. Carnegie Investment Bank AB sees it even lower at $20.

“Indirectly, lower oil price has a positive effect on the Johan Sverdrup project, as it has contributed to significantly lower capex,” said Carnegie analyst Kjetil Bakken.

Sverdrup, which is expected to produce for 50 years, was discovered in two parts by Lundin Petroleum AB and Statoil in 2010 and 2011. It now represents a lifeline for the industry as oil investments in Norway are set to drop for a third consecutive year and won’t rise again until 2019, according to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate. Norway is western Europe’s largest crude producer and depends on the offshore industry for about a fifth of its economic output.

Recommended for you