When the price of a 10-pound (4.5-kilogram) Atlantic salmon jumped above the cost of a barrel of crude last month, nobody in the oil industry was celebrating.

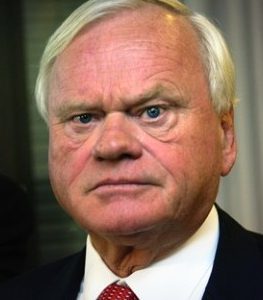

For John Fredriksen, who built a fortune on oil tankers and offshore drilling, it did at least provide some consolation. While his total net worth fell 40 percent to $10.6 billion in the past 18 months, the value of his investment in the world’s largest salmon producer climbed by half as fish prices rose to a record.

Fredriksen, who laid the foundation of his shipping fortune in the 1970s and 1980s by making daring bets in the conflict- ridden Middle East, has seen his about 25 percent stake in Marine Harvest ASA turn into his most valuable equity holding. That’s proving to be a boon for the 71-year-old Norwegian-born billionaire amid the worst crude market in a generation.

“Getting into fish was undoubtedly a smart move,” Kolbjoern Giskeoedegaard, an analyst at Nordea Bank AB, said in a phone interview. “What’s important for a system like the Fredriksen system, and which they’ve focused on increasingly these past years, is to put their eggs in several baskets.”

Fredriksen’s $1.6 billion Marine Harvest holding is now seven times as valuable as his similar-size stake in offshore driller Seadrill, formerly the mainstay of his empire before tumbling to record lows as oil-company demand dried up. Indeed it exceeds the combined value of his interests in Seadrill, crude-shipper Frontline Ltd. and oil trader Arcadia Petroleum Ltd., according to Bloomberg’s Billionaire Index.

The shipping tycoon got involved in salmon farming in the middle of the last decade as animal diseases such as avian influenza were prompting some consumers to seek other sources of protein, such as seafood. Just as Seadrill prospered during the oil-boom that followed its founding in 2005 and helped Fredriksen weather an extended downturn in the tanker market, Marine Harvest is providing a cushion to the slump in crude.

Fredriksen, now a citizen of Cyprus, has signaled he intends to hold on to his position in Marine Harvest, Chairman Ole Eirik Leroey said in an interview in Aalesund, Norway last week.

“He’s one of the most logically thinking people I’ve met,” Leroey said. “He likes operations, he likes organic growth, he has an unbelievable ability to identify good performances and to demand continuous improvement.”

Fredriksen also has a record of tapping his companies for dividends. The 12-month dividend yield at Seadrill was close to 11 percent in August 2014, when it announced its last payout, before market turmoil forced the company to halt distributions a few months later. Marine Harvest has a policy of distributing at least 75 percent of free annual cash flow to its owners.

“We have a main shareholder who makes sure we keep that up,” Leroey said during a speech. “You can rest assured of that.”

Seadrill has dropped 93 percent since June 1, 2014 as the collapse in oil prices led producers to cut spending, eroding demand for services such as drilling just as a wave of new vessels added to oversupply. Fredriksen’s stake in Seadrill is now worth about $212 million, similar to his initial 2005 investment in the company, according to estimates.

Marine Harvest has jumped 75 percent over the same period as shortages pushed up salmon prices and demand rose from Europe to Asia. The shares last week climbed to the highest levels since October 2003, before the company was acquired by Fredriksen’s PAN Fish ASA in 2006.

While the world is drowning in oil, it can’t get enough salmon.

“Global production potential has been capped, at least for a while,” Nordea’s Giskeoedegaard said. Even after the recent stock surges, “we see a 15 to 20 percent upside potential in the salmon industry,” he said.