A chain of events that followed the arrest of former Hong Kong minister Patrick Ho a year ago in the U.S. has collapsed more than $10 billion of deals across Central and Eastern Europe, an embarrassment for China that could spur a change in the development of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s grand plan for a New Silk Road.

Ho, whose trial is set to begin on Monday in a federal court in Manhattan, was charged under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act with corruption and money laundering. Prosecutors say he wired $900,000 to African officials via New York as part of a bribery scheme to win advantages for Chinese oil company CEFC China Energy Co. Ho pleaded not guilty and has been denied bail five times.

Following his arrest, Chinese media reported that the leader of CEFC, Ye Jianming, was under investigation by authorities in China. In October, state television said a former party chief in Gansu province had been accused of taking bribes from Ye.

Ye had turned CEFC from an obscure oil-trading startup in Eastern China into an international energy giant, with a string of deals in Asia, Europe and the Middle East that had been some of the highest profile contributions by a private company to Xi’s New Silk Road, now part of the Belt and Road Initiative. Ye had appeared in Xi’s entourage during a state visit to the Czech Republic, where he became a special adviser to the Czech president, and had had a deal in Kazakhstan publicly endorsed by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang.

“It’s bad for BRI because it ties it to corruption and financial and political risks,” said Andrew Chubb, a postdoctoral fellow in the Columbia-Harvard China and the World Program. “They want to increase outbound investment in a range of infrastructure projects by pushing the BRI idea, yet they want to control outbound investment by private companies.”

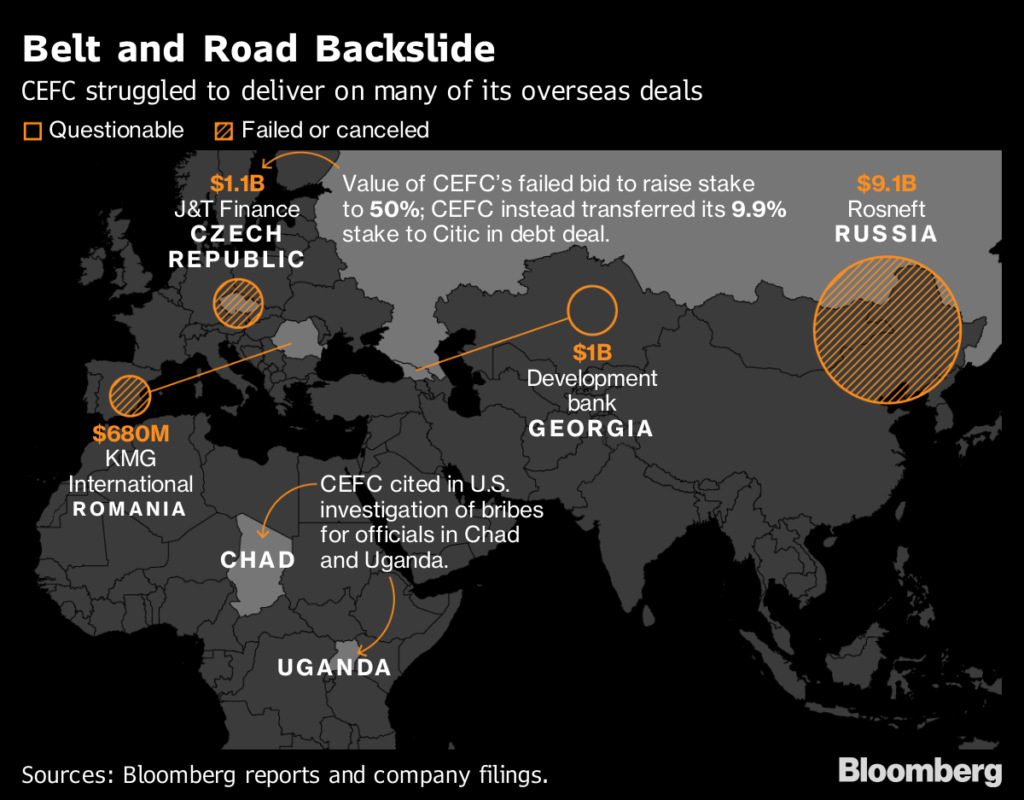

Many of CEFC’s overseas ventures collapsed after Ye’s detention, including a bid to buy 14 percent of Russian oil giant Rosneft, fueling concern among nations who have received Chinese investment pledges that even projects supported by China’s leaders could fall foul of China’s anti-corruption drive.

“Central and Eastern European states are asking where the investments are” that Chinese companies have promised, said Francois Godement, a French historian and director of the Asia and China program of the European Council on Foreign Relations. “Which projects are actually going ahead?”

For many states in the region, China offered a new alternative as an economic ally, without the Soviet-era baggage of Russia, or the long, protracted admission process of the European Union.

Nowhere did this new order, and the sea change in the fortune of CEFC, have a greater relative impact than in the tiny nation of Georgia.

With a population fewer than 4 million, Georgia has been little more than a footnote in global politics since a war with Russia a decade ago, but it occupies a unique geographical position on Xi’s New Silk Road. Halfway between the borders of China and Western Europe, its sliver of coastline on the Black Sea is the only route across Asia into Europe that doesn’t run through either Russia or Iran and Iraq.

That made it a target for Chinese companies looking to make investments that would mesh with China’s Belt and Road strategy.

At a conference in Beijing in May of 2017, Georgia’s then finance minister Dimitri Kumsishvili endorsed Xi’s initiative, calling on Georgia to “revive the Silk Road.” He signed an ambitious deal with CEFC to revive Georgia’s biggest free trade zone, on the Black Sea port of Poti, after the previous partner, a Gulf emirate development body, struggled with corruption of its own officials.

CEFC also agreed to establish both a national construction fund and a development bank modeled on the Beijing lender that financed China’s conglomerates. Coming on the back of a new trade deal with China, Kumsishvili said at the conference it was “the best period in history” for Georgian-Chinese ties.

In February, Ye was arrested and CEFC began a retreat from its expansion into former Soviet territory. The deal with Rosneft collapsed, and its plan for a $1.1 billion deal to increase its stake in Czech group J&T fell through. CEFC’s buyout of Romanian assets from Kazakhstan’s state gas company — the deal christened by Premier Li — was scrapped.

In Georgia, CEFC’s backtrack has raised questions about whether projects will go ahead and who will run them. Kumsishvili resigned in Georgia’s latest political overhaul and new finance minister Ivane Machavariani said “there is nothing yet in the pipeline” for the development bank, 18 months after the deal was announced.

In the free-trade zone, CEFC has a $150 million obligation, said David Ebralidze, the project’s chief executive officer. So far, he said, the company is “in full compliance with the share purchase agreement” after putting down a $10 million guarantee.

But Georgia did the deals with a private company and now it may be working with a new partner — the Chinese government.

CEFC’s assets in the Czech Republic, where Ye was so influential he was appointed as an official adviser to President Milos Zeman, have already come under the control of Chinese state-owned investment giant CITIC Group. The Shanghai government’s investment arm intervened in CEFC itself to manage the restructuring, and China Development Bank, its biggest creditor, has since stepped in amid debt negotiations.

CEFC didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Other high-profile Chinese entrepreneurs have fallen afoul of government probes in the past, including Anbang Insurance Group founder Wu Xiaohui, who was sentenced to 18 years in prison for a $10 billion fraud. Companies including HNA Group and Dalian Wanda Group that expanded aggressively by borrowing have faced scrutiny by regulators about their debt levels and have been selling assets.

But many of those examples fell into what Chinese authorities termed “irrational” overseas investments when it set out new rules for outbound investment in August 2017, banning industries like gambling, restricting sectors like property, hotels and entertainment, and encouraging investment in Belt and Road projects. CEFC had been seen as working in tandem with those interests, securing oil supplies and making investments in Belt and Road partner countries.

The share of private investment in the Belt and Road initiative fell by 12 percent in the first half of 2018 from a year earlier, according to a report by Washington-based American Enterprise Institute. The downfall of Ye may send a further warning to Chinese private companies that Xi’s control over investments abroad is tightening, said David Zweig, a political science professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

“He has clearly killed some chickens and the monkeys are watching,” Zweig said, alluding to a Chinese idiom for making an example of someone to scare others into behaving.

At a conference in Beijing to mark the fifth anniversary of BRI in August, Xi stressed that the new priority of the global initiative was to ensure the “high quality” of projects that deliver benefits to local people.

Hui Chen, a former compliance counsel expert at the U.S. Department of Justice, said that for China to improve compliance the government would need to prosecute both individuals and companies. “Chinese companies would need to see corruption as not profitable, and their executives will have to believe it is too personally risky, for changes to occur,” he said.

The arrest of Ye and the control of his company by state-run enterprises and banks could send a warning to other private investors.

CEFC, which at its peak claimed $40 billion in revenue, isn’t alone in making investments in Eastern Europe that turned sour. In Ukraine, ex-billionaire Wang Jing’s buyout of a state-owned jet-engine company has been upset by an investigation from the country’s Security Service. Romania’s negotiations with China General Nuclear Power Corp. for $7 billion of atomic energy plants have been extended several times. And Poland fought for years with Chinese group Covec over a botched highway deal before reaching a settlement last year. The Chinese companies didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The fallout for CEFC has been much wider.

Around the time of Ho’s arrest, CEFC failed to secure financing for its Rosneft bid. A report in Chinese media site Caixin in March said that some of CEFC’s revenues were inflated by fake trading, a practice that was used to gain access to financing. Ye denied the allegations at the time.

The bad debt company that bought a stake in the CEFC unit later faced a graft investigation and the arrest of its chairman. In China, filings show that publicly traded CEFC Anhui is having its accounts investigated for false reporting, and CEFC Shanghai has missed bond payments.

With Ho’s trial in New York set to begin soon, the damage to China’s overseas image could get worse.

“The Patrick Ho case, and the case of Chairman Ye and CEFC more generally, is a big problem for the BRI,” said Chubb, who has been following CEFC closely.

Chubb said Ho’s defense purportedly will argue he was acting as an agent of the Chinese state, promoting the BRI, and thus engaging in general goodwill activities on behalf of China rather than bribery for commercial gain.

“If they go ahead with that line of argument,” Chubb said, “it would amount to Ho and his CEFC-funded legal team deliberately linking his allegedly criminal actions with Xi’s flagship foreign policy initiative.”