North Sea oil and gas producers are on track to cut harmful emissions of carbon dioxide and methane, but the “intensity” – or dirtiness – of pollution from the basin has risen.

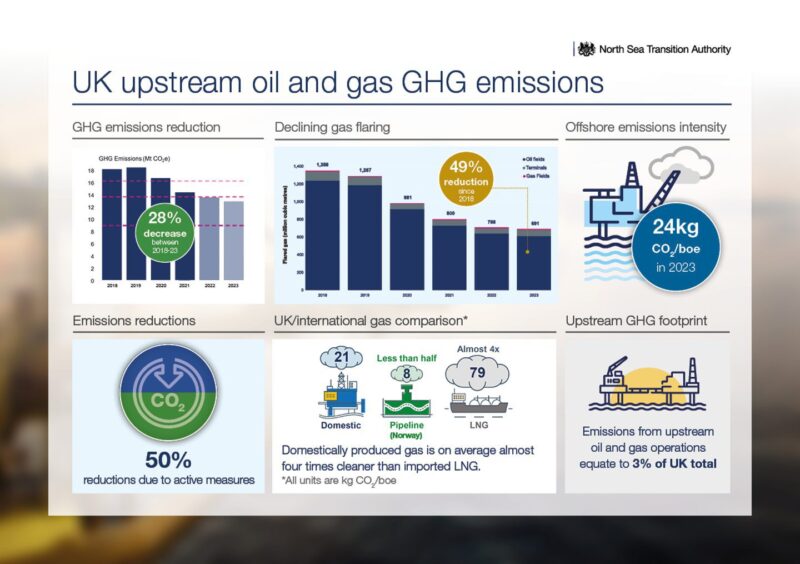

This is the finding of the latest Emissions Monitoring Report from the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA), which found operators of oil and gas platforms reduced the amount of green house gases (GHGs) emitted in 2023 by 4%, the fourth year in a row the industry has continued to clean up.

However, while the amount of carbon emitted on gas produced in the UK North Sea is four times lower than imported liquified natural gas (LNG), North Sea emissions are higher than the gas imported from Norway via pipeline.

This means that it is important to keep producing, particularly gas, in the North Sea instead of relying on imports but that there is potential for improvement” on lowering emissions faster like Norway has done.

The regulator, which said it is “holding the sector to account through robust stewardship and regulation”, said the reductions meant there has been an overall reduction of 28% between 2018 and 2023.

The sector is required for this to be 50% by 2030, 90% by 2040 and “net zero” by 2050. NSTA said the first target is “within reach”, but warns that “more work is needed to ensure that industry meets and surpasses key emissions targets”.

NSTA said the reductions were due to a combination of emission reduction measures such as flaring and venting, which releases gas and methane directly into the air. But half of the reductions were due to the North Sea’s ageing producing assets being offline or coming to the end of production.

NSTA said there had been a 49% reduction in flaring in the same five-year period.

The regulator said that was due to more efficient operations but also stricter controls and fines for activity that is deemed “unpermitted”. The body added it would start to name and shame the assets that are still flaring routinely in the coming months in an effort to reduce this further under a policy known as zero routine flaring and venting (ZRFV) by 2030.

However flaring still accounts for 17% of total upstream GHG emissions, NSTA found.

Why is carbon intensity rising?

Emissions intensity – greenhouse gases emitted for every barrel produced – is projected to have increased, as production has also fallen. Intensity increased to 24kg of CO2 per barrel of oil (boe), up from 22KG on the previous year.

NSTA said emissions intensity is “common in more mature basins”, but” this should not be used as an excuse to let performance slip”.

However, it added this trend is likely to continue as the decline of North Sea production continues or even accelerates.

NSTA further added that older assets which tend to be more polluting could be shut down earlier than initially planned.

However, due to declines in methane emissions – the UK North Sea is on track to have reduces these by 30% in 2023, well ahead of the Global Methane Pledge which has this target at 2030.

NSTA said UK upstream offshore emissions intensity is still more than 30% lower than the global average, but said the UK “must continue to compare favourably with

other nations to retain its social licence to operate”.

Hedvig Ljungerud, the NSTA’s director of strategy, said: “Cutting greenhouse gas emissions by more than a quarter in five years is an impressive achievement in the North Sea, where operators have taken real action and made substantial investments. However, for domestic production to be justified, it must continue to become cleaner.

“The NSTA will hold industry to account on emissions reductions, including on decisions today that could have an impact for decades to come, to ensure the nation can benefit from its domestic resource even as we transition.”

In addition to reducing emissions on platforms and other producing assets, North Sea operators will have to invest in “further abatement” in order to hit the emission reduction targets.

These include electrification of offshore facilities and deployment of flare and vent reduction technologies, NSTA said.

Some have raised concerns about the viability and costs of these investments.

However, industry has been developing proposals for more than a dozen major decarbonisation projects, mostly involving platform electrification and flaring reduction.

For example, TotalEnergies (PARIS:TTE) recently committed to a significant investment in a flare gas recovery system at the Elgin-Franklin field. Also, since last year’s report was published, the potential first-power date for a major, full-electrification scheme has been moved forward and a partial electrification project has been sanctioned. An electrification-ready development also received consent.

NSTA said operators should quickly press ahead with decarbonisation proposals, as the volume of emissions which can be avoided is diminished the longer it takes to commission a project.

Electrification, or an alternative source of low-carbon power, has the greatest potential for emissions reductions, as fuel combustion for power generation makes up four-fifths of production emissions, and so it is important that operators make final investment decisions on more of these projects.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by NSTA

© Supplied by NSTA © Supplied by EEMS/NSTA

© Supplied by EEMS/NSTA © Supplied by NSTA

© Supplied by NSTA