James Hackett is on a mission to become an evangelist for capitalism and responsible fossil fuel development. He poses, with all seriousness, a rhetorical question that makes a lot of people of a certain political persuasion uneasy these days: Can God, free markets and oil mix?

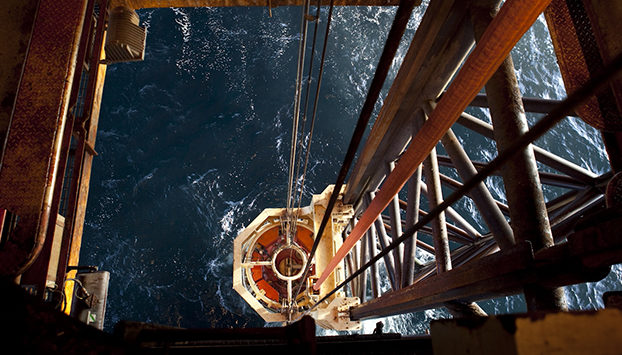

Hackett knows a lot about oil and gas. He became chief executive officer of Anadarko Petroleum Corp. in 2003, taking charge of a sputtering bit player thought to be takeover bait and turning it into a respected deep-water driller with $45 billion in strategic deals. Then, at the top of his game in May 2013, he stepped down for what some friends called a shocking career detour: Harvard Divinity School.

On a recent day, Hackett the deal maker, whose stewardship included steering Anadarko through the bleak days of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Gulf of Mexico oil spill, is pondering a more academic worry. He’s a year away from completing his master’s of theological studies and needs at least an A-minus on a Spanish scripture exam.

“Como estas?” he says with a trace of upbeat nervousness.

The deeper questions, Hackett says in a series of interviews aimed at explaining how he came to this fork in the road, are how the world is doing and what’s the proper role of capitalism and fossil fuels in making it a better place.

Make no mistake — though Hackett was propelled to divinity school in part by the excesses and failures of capitalism, the Enron Corp. debacle among them, he has a frank faith in God. He believes in the moral force and obligation of Christianity to improve lives with a capitalistic ethos.

‘Moderator on Capitalism’

“Christianity was always supposed to be a moderator on capitalism, and there has to be a moderator, a control system,” Hackett says as he relaxes on a chair in his palatial home on what could be termed oil-CEO row in Houston’s River Oaks neighborhood. “When you make this money, when you provide these jobs, there is a duty you have because you’ve been blessed by God to shepherd that wealth. And you have to do it well.”

Hackett, 61, is also not naive. At a time when Pope Francis is seeking to turn climate change into a pressing moral issue, religion is losing power in public life and a Gallup poll shows oil companies are less respected than every industry except the federal government, he has his work cut out for him. His ultimate goal, he says, is to obtain a teaching position at a major university where he can deploy his real world experience and spiritual leanings to influence the debate.

Faith in Technology

Hackett makes it clear that he isn’t a climate-change denier, and acknowledges the threat posed by warming temperatures. He sees technology, not overwhelming bureaucracy, as the solution and thinks those who make climate-change the central human problem to resolve are underestimating the equally challenging issues of food, water and energy security.

“Free markets, and oil and gas, will be critical to meeting those needs,” says Hackett.

At Harvard, Hackett has become a well-regarded figure among many of his classmates — which isn’t the same as saying they always agree with him. Ben Marcus, a fellow student who led a spiritual literacy discussion series last fall that featured Hackett as a guest speaker, says many students aren’t sure business and faith can work together.

‘Immoral’ Companies

Marcus, who graduated in May, rattled off a number of examples of where the two have clashed, such as when Hobby Lobby Stores Inc. fought and won a U.S. Supreme Court battle over whether the company could be compelled by the federal government to provide insurance for contraception.

“I know a lot of people at the divinity school who see some of the practices of Anadarko and other companies as immoral,” says Angela Thurston, a classmate who heard Hackett speak at the lecture. “But he has always insisted Anadarko and oil companies can be values-based.”

Hackett’s unusual walk with God began with the collapse of energy trading conglomerate Enron, where he felt stung by the failure of values in the company’s demise. Enron CEO Jeff Skilling — now in prison — was one of Hackett’s MBA classmates, and he knew many of the company’s leaders well. Enron, he recalls, touted “communication, respect and integrity” among its core values, yet at the end of the day failed on all counts,he said.

As a senior executive or CEO at companies including Duke Energy Corp., Seagull Energy Corp., Ocean Energy Inc. and Devon Energy Corp., Hackett has always emphasized the importance of values, instilling corporate ethics at one company that mirrored principles in the Ten Commandments, he says.

Enron Lessons

Seeing Enron spiral into a criminal morass convinced him he needed a career change. Hackett wanted to do more, to teach up- and-coming business leaders about the importance of spiritual values during crises. Hackett’s religious convictions were forged in a trying freshman year at the U.S. Air Force Academy, where he attended for two years before finishing college at the University of Illinois. They helped him deal with the Macondo blowout, the worst offshore oil spill in U.S. history. Anadarko was a 25-percent partner with BP Plc in the well and eventually settled most of the damages for $4 billion.

Hackett’s proteges say the boss learned from that experience. “One of the things he taught me is that especially as you ascend in a company, as you climb into leadership positions, sometimes it can be kind of lonely,” says Chris Doyle, who worked for Hackett at Anadarko and who is now an operations executive at Chesapeake Energy Corp. “You’re going to be put in situations where you may not know where to turn, but you can build a line of communication with God.”

Hackett, a Catholic, isn’t the only spiritually inclined, high-profile leader to tackle the contentious issues of capitalism, pollution, climate change and values.

Papal Disagreement

Pope Francis electrified the world this month with his encyclical on climate change, declaring among other things that a “perverse” economic system has turned Earth into “an immense pile of filth.” He called for fossil fuels to be “progressively replaced without delay.”

Hackett’s view, stated politely, is that the Pope is plain wrong.

“He is wrong about hydrocarbons writ large,” Hackett says. “While I love his hope for an idyllic world of endless, affordable and scalable carbonless energy produced outside of a capitalist system, social history would suggest that we need to continue to apply innovation, risk and reward, and technology to the problem, not just prayers and encouraging words.”

Renewable Energy

The world could soon get by without coal, but not without oil and gas, in Hackett’s view, as technologies including solar, wind and other renewable sources aren’t close to providing the energy the world needs. The technologies are too susceptible to interruptions without a breakthrough in battery storage. Recalling the environmental problems of the 1970s, such as ozone damage and air pollution, Hackett says things have improved — and technology was the major driver.

Pope Francis, he says, is too pessimistic and too dismissive of the benefits that technology and private enterprise can deliver for the world.

“People like the pope need to understand what the capabilities of the secular world are to deliver on God’s promises for us,” he says. “God made us to be good and to do good, and if you can’t do good through work, there’s a missing part of God’s plan.”

Recommended for you